From ideas to laws – how Energiewende policy is shaped

German energy policy used to be mostly about the secure and economical supply of power, gas and heat. Sustainability, efficiency, consumer-friendliness and climate protection now make the field more complex and mean new stakeholders now influence the legal process.

Federal legislation

Germany’s national parliament, the German Bundestag, decides on the country’s federal laws. The Renewable Energy Act (EEG) and the Energy Industry Act (EnWG) are among the most important energy laws.

The German Bundesrat, which is the council of the 16 federal state governments, has to be consulted for legislation to be enacted. In most cases regarding energy policy, a majority in the Bundestag can overrule a Bundesrat veto.

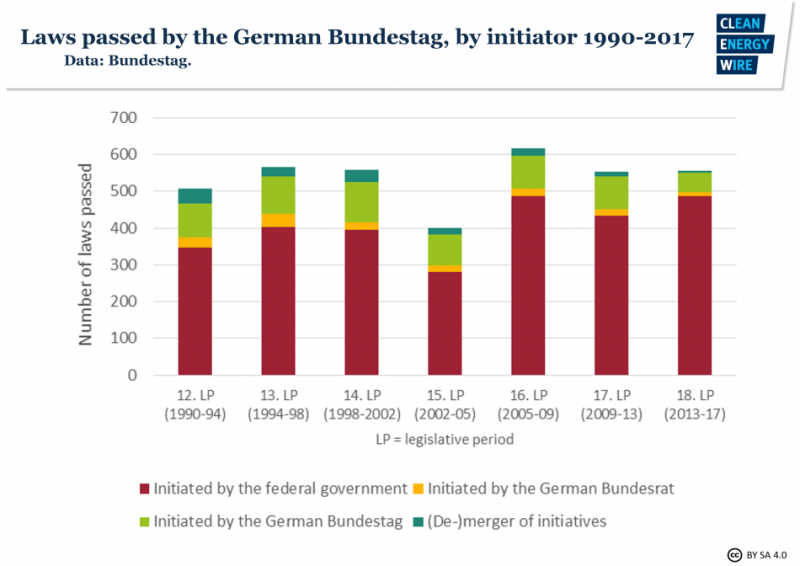

Three institutions have the power to initiate a federal law: The Bundestag, the Bundesrat and the federal government (Bundesregierung). The impulse for most new or reformed legislation comes from coalition agreements or government programmes at the beginning of a legislature, or through changes in EU regulations.

On average, more than 70 percent of all ratified laws derive from federal government proposals. This factsheet mainly concentrates on these. Most of the laws are drafted by policy officers in one of the ministries. The respective federal minister is responsible for the project. For energy, this is the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi); on climate, the BMWi shares responsibility with the Federal Ministry for the Environment (BMUB).

Legislative texts are drafted in consultation with stakeholders such as federal and local administration, science, special government or parliamentary commissions, political parties, industry and civil society. The ministries may employ external experts to help draft the legislation. Interim drafts are rarely published.

To avoid disputes later in the process, contentious points are often debated at federal government coalition meetings and the resulting decisions incorporated into the ministry draft.

Info Box: Green / White paper

Where the scope of the new legislation is not yet clear, or input is wanted from stakeholders such as industry, civil society, science and other experts, green and white papers can be a preliminary stage of legislation.

A green paper lays out proposals and theses on a certain topic. It is meant to guide and fuel the public and scientific debate on policy objectives, and often results in the creation of a white paper, which then contains more concrete regulative proposals. One example is the 2016 Green paper on energy efficiency meant to find solutions for the long term reduction of energy consumption in Germany.

Once the draft bill is finalised, it is approved by the Chancellery and coordinated with all affected ministries. This stage can be subject to intense debate over certain provisions, especially if a law touches on several policy areas at once. The final draft is then approved in a federal government cabinet meeting and can be sent to parliament.

The Bundesrat must give its opinion if a draft is introduced by the federal government. This is not the case if a parliamentary group in the Bundestag initiates a proposal directly. Therefore, to save time and avert disputes with federal state governments, drafts originating in a ministry are often introduced directly by the governing parliamentary groups.

After a first reading in a Bundestag session, the draft bill is considered by relevant committee(s), where hearings and inquiries can take place. Changes are made and a revised version is passed back to the full Bundestag chamber with a report and vote recommendation. A second reading may include debate and further amendment proposals. The third and final reading may include debate, after which a final vote is taken.

This procedure gives the political groups in the parliament several opportunities to set policy priorities and insert additional provisions into the draft.

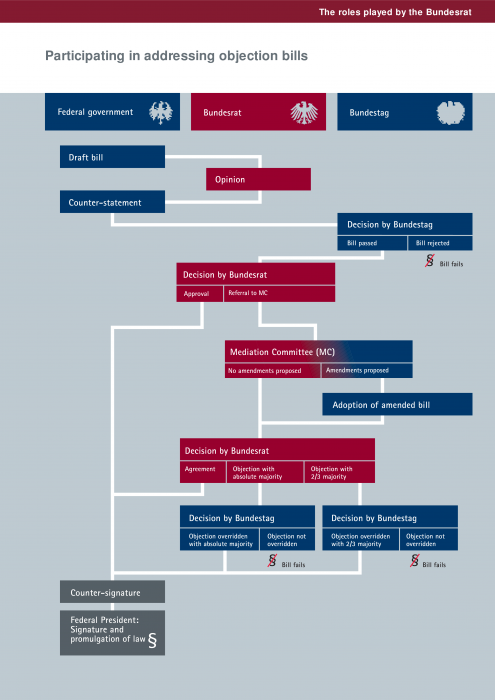

If approved by the Bundestag, the bill is sent on to the Bundesrat for the consent of state governments. If the Bundesrat objects to a draft, a mediation committee made up of 16 members from both institutions is tasked with trying to find a compromise.

However, most energy-related bills are so-called objection bills. This means that if the mediation process fails to result in an agreement, the Bundestag can override the Bundesrat’s veto. Consent bills, on the other hand, require Bundesrat approval to pass.

The next stage is for the Federal President of Germany to formally sign the bill into law.

16 states of mind

The federal government has legislative power over Germany’s economic matters, including energy (Article 74, Basic Law). German federalism, however, allows individual states to leave their mark on national energy policy.

State governments can participate (or intervene) in federal legislation via the Bundesrat (as shown above) and have flexibility over how they interpret legislation when they come to implement it. States can also pass their own bills in certain areas of energy policy, such as toughening up efficiency standards in state building and planning regulations.

For more information on the federal states’ powers, read the CLEW factsheet German federalism: In 16 states of mind over the Energiewende.

The influence of EU law

EU law strongly influences German energy and climate policy in several ways:

A. EU treaties and legislative acts (regulations, directives, decisions, recommendations and opinions) are the main way the Union shapes German law. Treaties and regulations are binding texts that must be applied directly in all member states.

The treaties lay out general aims such as “combating climate change”, ensuring “the functioning of the energy market”, “the security of energy supply”, and promoting “energy efficiency and energy saving” (Art. 191 and 194 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)). Regulations and directives determine the details.

A "directive" is a legislative act that sets out a goal that all EU countries must achieve. However, it is up to the individual countries to devise their own laws on how to reach these goals. One example is the Energy Efficiency Directive. Because of lagging enactment into national law, the EU Commission threatened financial penalties if Germany failed to ensure the full transfer of the Energy Efficiency Directive.

B. Competition law – especially on questions of state aid (Art. 107 TFEU) – is another important way for the EU to influence policy in the member states. The Directorate General for Competition decides if national state support schemes distort, or threaten to distort, free competition within the EU. For instance, the Commission could object to national regulation supporting certain energy sources. The German government often aims to clear legislation with the Commission before enacting it. A recent example in summer 2016 was the agreement on state aid-related aspects of an energy regulation package that included support for combined heat and power (CHP) plants.

Influence of individual actors

Individual actors can have a big influence on Germany’s energy and climate policy shaping, depending on the situation. This is not limited to the head of government (e.g. “Climate Chancellor Merkel”), but can include federal ministers, or individual members of parliament with in-depth knowledge or a special interest in certain policy areas.

Prominent examples include state premiers such as Baden Wuerttemberg’s Winfried Kretschmann of the Green Party – whose government recently decided to introduce a ban on older diesel cars to improve air quality in the state’s capital Stuttgart – and economy minister Peter Altmaier who as Chief of the German Chancellery coordinated the work of all ministries from 2013-2018. Altmaier’s preceding position as federal environment minister provided him with the necessary topical insight, and his former position as chief CDU whip in the Bundestag provided him with the political contacts to steer the country’s energy and climate policy.

Senior members of the executive bureaucracy, such as Germany’s highest civil servants in the federal ministries – the state secretaries – can also be influential. In many cases they are party-affiliated and chosen by the relevant minister. Among these are former state secretary in the economy ministry Rainer Baake and current state secretary in the environment ministry Jochen Flasbarth.

Beyond legislation

Many of the country’s goals in energy and climate policy are not codified in German law. They derive from government programmes and plans, and have been confirmed in documents like the Energiewende monitoring reports. A new government could, in principle, change or scrap these non-binding programmes when taking power. The most recent example is the environment ministry’s Climate Action Plan 2050, a basic framework for largely decarbonising Germany’s economy to reach 2050 climate goals. It includes targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in individual economic sectors and emphasises the need to ensure economic competitiveness throughout the transition.

Very little direct democracy

Germany is a representative democracy and referendums hardly play a role in national politics. A referendum would only be held when deciding on revisions of the existing division into federal states, or when adopting a new constitution, according to the Basic Law for Germany. On a federal level, the direct participation of the population is seen as inadmissible, to ensure that the decision-making powers government institutions are not weakened. On the federal state level, a referendum may be held when it concerns topics within the legislative power of the states.