Climate litigation advances to key tool for enforcing emission cuts

Historic cases

A full list of climate cases is available via the Sabin Center’s database of cases. Here are three influential cases from the Netherlands, Pakistan, and the United States.

In 2013, the Dutch NGO Urgenda brought a case to the District Court in the Hague against the government of the Netherlands for failing in its duty of care to citizens in respect of climate mitigation. The court accepted the case and ruled in 2015 that the government had a duty of care to its citizens under Dutch law and must cut its greenhouse gas emissions by at least 25 percent by the end of 2020 (compared to 1990 levels). The government appealed the decision but the Appeals Court upheld Urgenda’s victory and based the obligations to reduce emissions on human rights law. The decision was appealed for a second time but, at the end of 2019, the Dutch Supreme Court, the highest court in the Netherlands, upheld the decision of the Appeals court, thus upholding the emissions reduction order.

This outcome was ground-breaking for a number of reasons and set some important precedents which, whilst not legally-binding outside the Netherlands, are nonetheless influential. For example, subsequent cases in other countries have cited the decision by the Dutch court, to argue that each state must be held responsible to reduce its own emissions, regardless of the fact that climate change is a problem to which all contribute.

In the wake of the decision, Urgenda has been approached by people from all over the world interested in bringing similar cases. The lawsuit has spawned at least 37 similar cases in countries around the world, including Germany, France, Brazil, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and Italy. With the Urgenda precedent, Friends of the Earth Netherlands was able to file a case, this time against oil major Shell.

The case in the Netherlands led to the closure of coal fired power plants and 10 billion euros of public money directed towards emissions reduction measures. That said, recent data suggests that emissions in 2021 may exceed the 25 percent limit stipulated in the court order. As a result, Urgenda is investigating the option of bringing enforcement proceedings to argue that the Dutch state is failing to meet its legally-binding emission reductions target. The NGO is seeking to find a way – via a system of fines – to hold the government accountable if it does not fulfil the instructions issued by the court.

Leghari v. Federation of Pakistan

In 2015, the farmer Asghar Leghari brought a case to the Lahore High Court invoking the twin rights to life and human dignity because drought was threatening his harvest and ability to live. Leghari argued the Government of Pakistan was failing to implement its National Climate Change Policy of 2012 and the Framework for Implementation of Climate Change Policy (2014-2030), violating his fundamental rights. The court's clear articulation of the connection between water justice, climate justice, and fundamental rights makes it globally significant. Reasoning that intervention was needed to promote the implementation of climate action, the court constituted a climate change commission comprising climate change experts and high-level members of the federal government. Furthermore, the judge required regular update reports from the commission on its progress in implementing the climate policy. In 2018, the Climate Change Committee reported that during the period from September 2015 to January 2017 two-thirds of the priority actions from the Framework for Implementation Climate Change Policy had been implemented.

This is one of the most seminal cases in US environmental law, filed in 2003 and decided in 2007. The Supreme Court ruled that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has the authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions under the Clean Air Act, as argued by a group of states, local governments and environmental organisations. Subsequently, the EPA acted upon the Supreme Court decision and enacted policies for regulating vehicle emissions, forcing car manufacturers to double the fuel economy of all new cars and trucks by 2025. The EPA also released the 2015 Clean Power Plan designed to lower power plant emissions by 32 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. Legal scholar Cinnamon Piñon Carlarne argues in Debating climate Law that the accumulated effects of Massachusetts v. EPA limited ‘the speed and the extent to which the Trump Administration was able to dictate the executive rewriting of national climate law’ in the USA.

What kinds of tools can litigants use to fight climate cases?

Rights-based cases are a new and important section of climate litigation. These cases often garner the most attention because they are dealing with the most important laws we have, such as the protection of right to life. Some people call these cases systemic cases because they aim to change fundamental principles of the legal system. They can also be described as strategic litigation because part of their power is to raise awareness and mobilise the public. Rights-based cases are a relatively new development in climate litigation.

Planning and environmental assessment cases: Planning application cases aren’t flashy but Joana Setzer of the Grantham Institute argues that they are nonetheless important cases which, cumulatively, have a significant impact.

Greenwashing cases: The climate law NGO Client Earth has taken BP and other major polluters to court for misleading the public with greenwashed advertising, using consumer law as the basis of their argument. Client Earth says that ‘these litigation efforts are putting oil and gas companies on notice, and this kind of pressure can lead to a shift in company behaviour towards more climate-friendly policies.’

Company Law cases: Commerce and finance laws are an effective way of moving markets and investment away from fossil fuels, forcing investors to consider the risk of climate change. One recent example is a case brought by Client Earth against the Polish utility Enea. The NGO bought shares in the company and then brought a case arguing that it was violating its duty of care to shareholders by developing a coal power station that would become a stranded asset before it had made a profit. Client Earth won the case in 2019.

What are some of the most important differences between jurisdictions when it comes to climate litigation?

It is clear that in climate change cases judges are increasingly paying attention to decisions made across the world, regardless of jurisdictional differences. As British-French lawyer Philippe Sands recently put it in an online seminar on climate litigation organised by Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung: “you can see when you talk to national judges they’re looking over their shoulders; they don’t want to be the country that’s left behind” in terms of ruling progressively on climate action.

The Pacific islands of Vanuatu are currently spearheading an initiative to call on the UN’s principal judicial body, the International Court of justice, to issue an advisory opinion on the rights of present and future generations to be protected from climate change. This would theoretically create a universal body of legal principles applicable in all jurisdictions.

The nations of the world can broadly be divided into common and civil law jurisdictions. The majority are civil law jurisdictions, meaning that they use a codified system of laws by which to judge cases; the minority (including the UK, the USA, Canada and Australia) use a common law system meaning that there is no constitutional code and that courts base their decisions on existing precedents. Some countries have mixed systems.

Below are some further details about climate litigation in different regions:

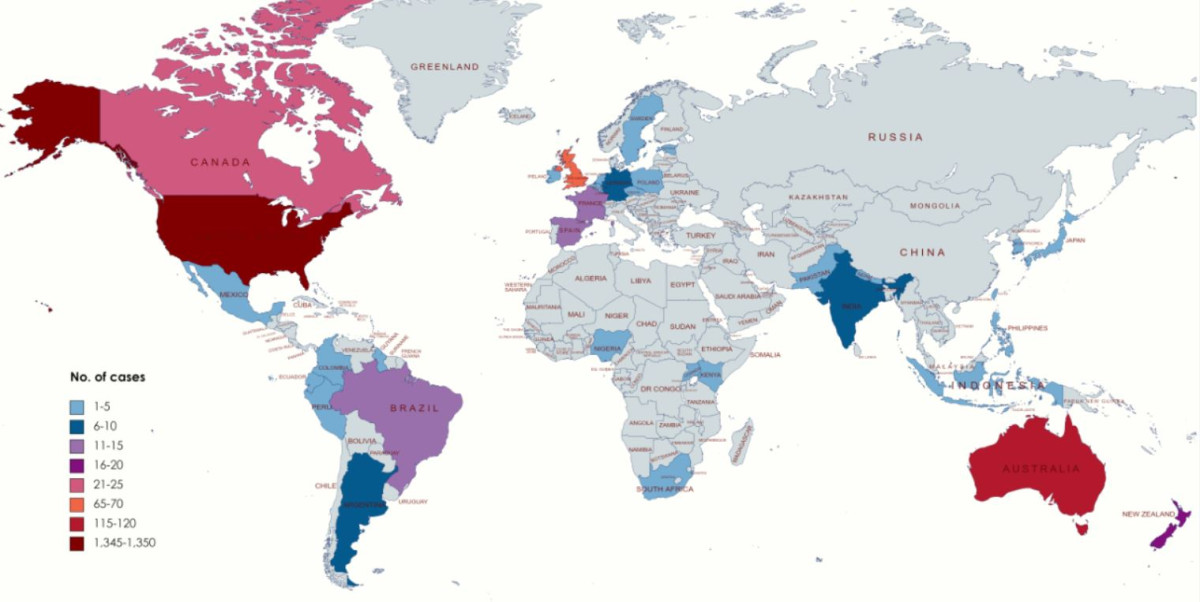

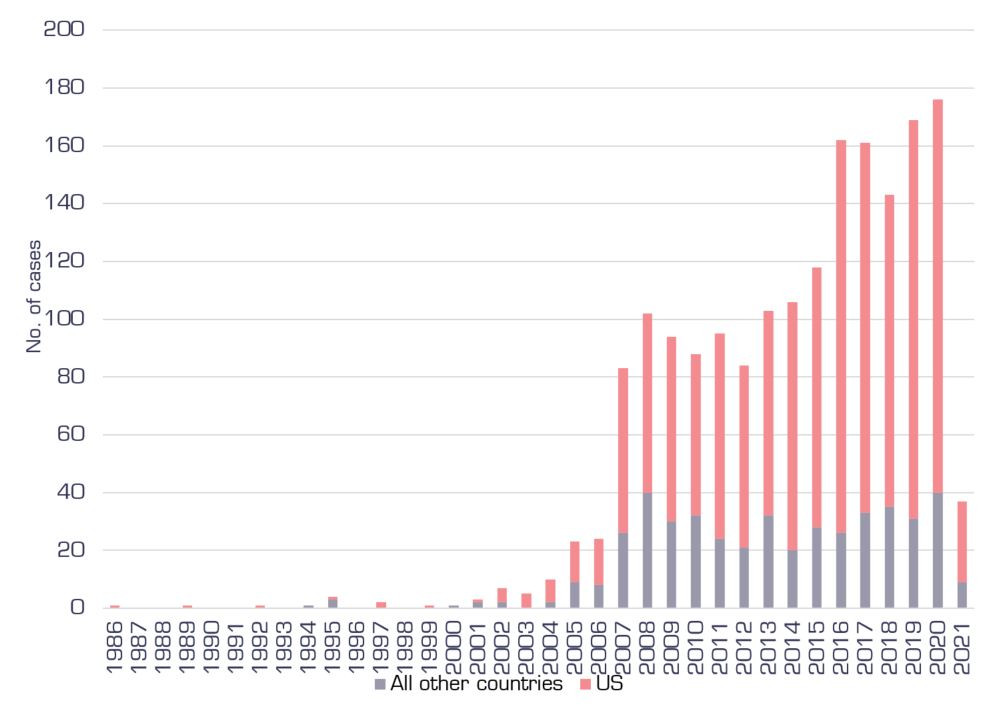

North America: The vast majority of all climate cases have been filed in the USA. This is for a few reasons. The US has a longstanding tradition of strategic litigation and it is relatively easy and cheap to file a case in the US (in many countries the loser has to pay, whereas in the US each party has to handle their own costs). The Biden government has set the target to become climate-neutral by mid-century, but will likely have to achieve it largely through administrative regulation under existing environmental and energy law because Congress has not yet passed significant climate change legislation. The major U.S. federal environmental statutes with private rights of action allow environmental groups and states who want action on climate change to turn to the courts. Cases normally revolve around enforcing existing statutes like the Clean Air Act or fighting particular fossil fuel projects like natural gas pipelines or power plants, through environmental review processes under state or federal law. There is also litigation in the other direction. When the government tries to enact pro-climate regulation, cases are sometimes brought against these efforts by industry and states who oppose climate action. Importantly, US courts have been unreceptive to cases based on torts or human rights law (such as in Juliana v. United States).

Europe: Following the inspiration of Urgenda, Europe has been a centre for rights-based climate cases, with an unprecedented number of judgements coming out over the last couple of years. In April 2021, the German constitutional court found that the government’s emissions reduction programme violates the German people’s constitutional rights to life and dignity; it also found that the state is failing in its responsibility to future generations by acting too slowly to reduce emissions. The judgement concluded that ‘one generation must not be allowed to consume large parts of the CO2 budget under a comparatively mild reduction burden if this would at the same time leave future generations with a radical reduction burden . . . and expose their lives to serious losses of freedom.’ The German government was ordered by the court to revise its policies to reduce emissions. A week after the court's decision, the government agreed to pull forward its target date for climate neutrality to 2045.

Important judgements in rights-based cases have also been made in France, Belgium and Ireland. In Notre Affaire à Tous and Others v. France, the court judged the state to be illegally failing to meet its own targets but stopped short of imposing or demanding new targets. In Friends of the Irish Environment v. The Government of Ireland, et al., the court judged that the government needed to create a more specific plan for achieving its climate targets but wouldn’t go as far as to recognise the right to a stable environment, stating that this was the job of the European Court of Human Rights. Finally, in VZW Klimaatzaak v. Kingdom of Belgium & Others, the judgement found that the state was breaching constitutional and human rights commitments by not doing more to mitigate against climate change. However, it refused to order the government to act further, judging this to be beyond the limits of its powers.

In another major development, a number of climate cases have come to the European court of Human Rights during 2020. These cases are the first of their kind to be heard by the court: one is the case of the Union of Swiss Senior Women v. Swiss Federal Council and Others in which a group of women over 75 years of age argue that their rights to life and health are being violated by the Swiss government’s inaction. Their case was thrown out of the Swiss Federal Administrative Court on the grounds that women over the age of 75 are not the only people affected by climate change impacts, but the case was subsequently accepted by the ECHR. The second example is the case of Duarte Agostinho and Others v. Portugal and 33 Other States, in which six Portuguese young people argue that the member states of the EU are violating their rights to life and privacy and the right not to be discriminated against as young people who stand to experience the greatest impacts of climate change.

Australia: after the USA, Australia has the highest number of climate cases globally (though the numbers are small by comparison with the US). According to climate legal scholar Professor Jacqueline Peel, the inaction of the national government to institute an adequate climate policy has lead to strong efforts to use the courts to prompt action. There is a network of environmental courts at the state level, most prominently the Land Environment Court of new South Wales. Over the last few years several cases have sought accountability from government and corporate actors for failures to take adequate action on climate change. There have been cases using corporate law to pursue disclosure actions against banks and pension funds (such as McVeigh v. Rest) and against the government itself in respect of its sovereign bonds (O’Donnell case). There have been actions that seek to challenge the government’s policy of a gas-led pandemic recovery, sometimes using indigenous rights as the basis for the litigation. The New South Wales Land and Environment Court recently issued the important judgement that the NSW government has a duty to regulate climate change under existing environmental laws. The judge in this case, Chief Judge Preston, has been conspicuous for his pro-climate judgements. He has been criticised by some for being an activist but lauded by others as a leader in the field of judicial decision-making on climate change.

Brazil: Climate change litigation in Brazil relies upon existing environmental statutory and case law. Only very recently are cases being brought to court that reference climate directly. Climate legal scholar Professor Danielle de Andrade Moreira points out that the majority of climate cases in Brazil are indirect, many of them relating to land use changes such as illegal deforestation which are the main drivers of Brazil’s greenhouse gas emissions. Brazil has many climate laws at both federal and state level including the 2009 Climate Act. However, since President Jair Bolsonaro came to power at the beginning of 2019, Brazil has witnessed the dismantling of the administrative and legislative structure regarding environmental and climate policy. As a result, civil society and the public prosecutor’s office (which has a special role in Brazil to protect collective rights) have led litigation aimed at preserving the existing climate policy. The Institute of Amazonian Studies brought a case against the government in 2020 arguing that the Brazilian Constitution guarantees a fundamental right to a stable environment and the government must therefore be compelled to meet emission and deforestation reduction goals. Also in 2020, a coalition of opposition political parties brought two cases against the government arguing that the dissolution of the Amazon Fund and the Climate Fund was unlawful. Decisions are pending on all three cases.

South Asia: the countries comprising South Asia (Nepal, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka) have seen a number of very significant climate cases. According to lawyer Briony Eales, judges have the capacity to make a broad range of orders in this region and courts have relaxed the rules for standing in public interest environmental and climate litigation. Standing refers to the ability of plaintiffs to bring legal action. Constitutional writ petitions are popular in South Asia because plaintiffs can lodge their case straight to a country’s highest court, arguing that one of their constitutional rights is being undermined. In such litigation, judges may issue mandamus orders directing a government to perform a specific duty and continuing mandamus orders, in which courts keep matters open and require parties to report on progress with implementing the court’s orders. These two factors have contributed to a number of groundbreaking cases including Leghari v. Federation of Pakistan (see above) and Shrestha v. Office of the Prime Minister et al.

Looking at the wider Asia Pacific region, there has also been interesting litigation in the Philippines and Indonesia. Sometimes climate cases from Asia Pacific are not registered in global climate litigation databases because they may not explicitly raise climate change as an issue. Briony Eales expects that Asia will see more and more adaptation cases, potentially run as rights based litigation, as this region will be one of the earliest and worst affected by climate change impacts.

Cases to watch

Envol Vert et al. v. Casino

In March 2021 an international coalition of eleven NGOs sued the French supermarket chain Casino for its involvement in the cattle industry in Brazil and Colombia, which plaintiffs allege cause environmental and human rights harms. The alleged environmental harms include destruction of carbon sinks essential for the regulation of climate change resulting from cattle industry-caused deforestation, according to the Sabin Center.

This is an example of value chain litigation, which holds companies to account for failing to decarbonise their value chains or supply chains. The recent Shell decision in the Netherlands forces the company to deepen emission cuts in its global value chain. However, as Michael Gerrard of the Sabin Center points out, ‘the supply chain of a supermarket is far more complicated than the supply chain of an oil company, so it will be interesting to see what happens. I think it will be a further stretch in terms of applying the law.’

Petition of Torres Strait Islanders to the United Nations Human Rights Committee

In 2019, a group of eight inhabitants of the low-lying Torres Strait Islands, which are located between Australia and Papua New Guinea, submitted a petition against the Australian government to the United Nations Human Rights Committee. The petition alleges that Australia is violating the plaintiffs’ fundamental human rights under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) due to the government’s failure to address climate change, according to the Sabin Center.

The complaint is the first climate change litigation brought against the Australian federal government based on human rights, and the first legal action worldwide brought by inhabitants of low-lying islands against a nation state. The islanders argue that the Australian government has failed to protect the human rights of Torres Strait islanders on the climate frontline. They are facing climate change impacts to their homelands already – including sea level rise, more frequent severe weather events, increased flooding and coastal erosion. Over time, the islands could become uninhabitable due to climate change.

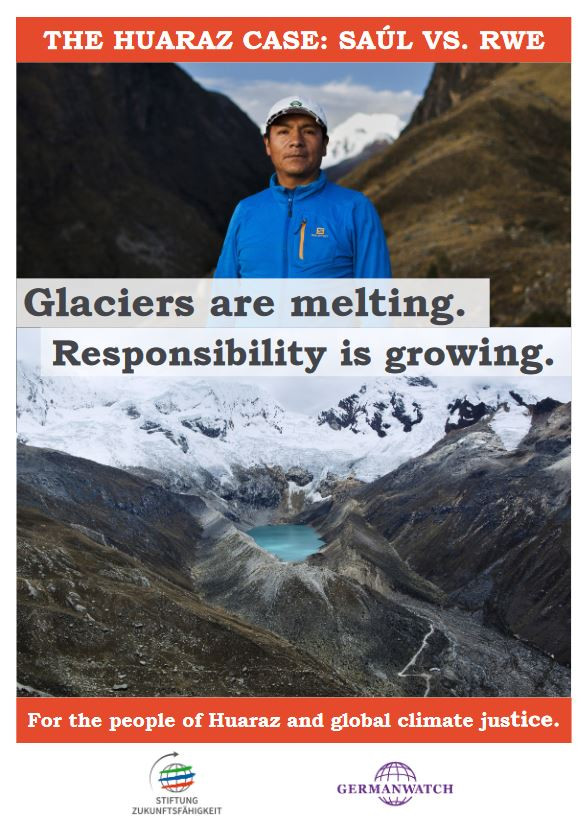

Luciano Lliuya v. RWE

In November 2015, Saúl Luciano Lliuya, a Peruvian farmer who lives in Huaraz, Peru, filed claims for declaratory judgment and damages in a German court against RWE, Germany’s largest electricity producer. Luciano Lliuya’s suit alleged that RWE, having knowingly contributed to climate change by emitting substantial volumes of greenhouse gases, bore some measure of responsibility for the melting of mountain glaciers near his town of Huaraz. That melting has given rise to an acute threat: Palcacocha, a glacial lake located above Huaraz, has experienced a substantial volumetric increase since 1975, which has accelerated since 2003, according to the Sabin Center.

This case is a property claim, based on basic nuisance law and the argument that Saúl Luciano Lliuya’s property is affected by RWE’s emissions. This is the first case of its kind to have got this far in the courts. Many are watching its progress because over ninety jurisdictions share the basic nuisance provision that is being used to fight the case.

This is also a significant case in terms of its demand for compensation. Saúl Luciano Lliuya is arguing that RWE should pay 0.47 percent of the adaptation costs associated with the glacial retreat above Huaraz. This is based on a study which attributes this share of global greenhouse gas emissions to RWE, and another study which analyses the role of anthropogenic climate change in the retreat of the glacier above the lake. Since Saúl Luciano Lliuya’s case was filed, several municipalities in the USA and one state (Rhode Island) have brought cases against oil majors seeking damages. These damages are measured according to product share theory, which determines the extent of a company’s liability based on their market share. All of these cases are pending.

Speaking to Clean Energy Wire, Dutch lawyer and Senior Associate at the University of Cambridge Professor Dr Jaap Spier expressed his frustration with the US cases. He stated that “the losses caused by climate change will be so colossal that it is simply unaffordable to compensate all or even most losses. My current stance is that we should be willing to think about compensation only for the poorest people and most vulnerable countries up to a point."

Trends to watch

We are likely to see more of the following types of cases:

- Rights-based cases, especially in jurisdictions with similar legal structures to the Netherlands or those with strong constitutional environmental rights

- Adaptation cases that deal with state/corporate responsibility to put in place measures that protect people from what are now unavoidable impacts of climate change such as wild fires, flooding, rising sea levels etc.

- Shareholder and investor actions and cases based on financial and company law

- Cases targeting specific government policies that are inconsistent with net-zero targets such as the case of Plan B v. United Kingdom

- ‘Just Transition’ cases are likely to become more prominent in the coming years, as activities aimed at reducing emissions (such as installation of renewable energy plants and the elimination of jobs in fossil fuel industries) will result in actions brought by affected parties, trade unions etc.

Advances in attribution science

Scientists are increasingly confident they can quantify the emissions resulting from a single company’s fossil fuel use and attribute specific impacts to specific polluters. This kind of attribution science is likely to become an ever more important tool in litigation. For example, a study has shown that climate change has made the recent deadly floods in Germany more likely.

Similarly, the new IPCC report will be an important resource for litigation concerning areas of the world likely to be most affected by the impacts of climate change. IPCC Assessment report 6 was cited for the first time in the case brought by the bushfire survivors to the court of new South Wales.

Noah Walker-Crawford, a research fellow at University College London, has studied the application of attribution science in the case of Luciano Lliuya v. RWE. He says it is essential that science holds up in court to a legal standard of evidence. In this case, the publication of precise scientific evidence relating to the emissions of RWE and the impacts of warming on Luciano Lliuya’s region have enabled the plaintiffs to construct a precise chain of evidence between the emissions of RWE and Luciano Lliuya and his property in Peru. When the case was filed in 2015, this was more difficult. Now, though, scientists have been able to calculate, not only the proportion of industrial emissions generated by RWE but also the extent to which anthropogenic climate change has contributed to the glacial retreat that is threatening Luciano Lliuya’s home. This kind of attribution science has never been tested in court before and the plaintiffs in this case are waiting with great interest to see how the court responds to this evidence.