Welfare groups urge power cost relief for German poor

Both welfare and green energy groups, as well as economic research institutes and politicians, have said more needs to be done to make sure the Energiewende is implemented in a socially equitable manner. The Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS) in Potsdam, for example, has a working group of experts focused on the social side of the Energiewende, which has proposed ways of ensuring a “socially fair” distribution of costs. According to IASS head and former environment minister Klaus Töpfer, dealing with social hardship is just as important as helping industry deal with costs associated with the Energiewende. “We have to try this in the social area too,” Töpfer told the Evangelische Pressedienst in early 2015.

A more “socially fair” Energiewende?

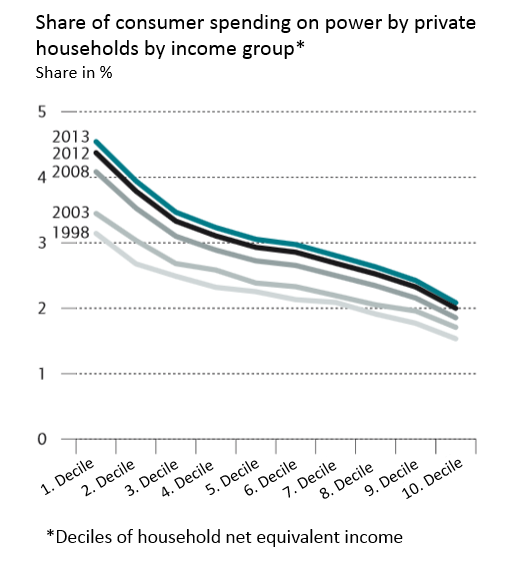

The Energiewende enjoys broad support in the general public, and rising incomes have kept the average share of monthly household spending on power steady at just under 2.5% for many years. This might be why rising electricity costs haven’t undermined support for the transition to renewable energy. But people in low income brackets pay a greater share of their income for power – over 4% for the bottom two tenths since 2008, according to a 2012 study by economic research institute DIW “Households with the lowest income are especially adversely affected by the current price increases,” DIW said in the report. Given these figures, it does not come as a surprise that approval of the Energiewende is lowest among people on low incomes.

Many poor can’t afford to save energy

Many people on the verge of poverty are trapped in a vicious circle of high consumption and high prices, because they simply can’t afford to save energy. A more efficient washing machine or LED bulbs, both of which would cut their electricity bills, are often out of reach financially. Energy efficiency measures, such as building insulation, often push up rents, even if they also cut costs in the long run. These problems are compounded when power and heating prices rise, say poverty experts like the Federation of German Consumer Organisations (VZBV), welfare group Deutscher Caritasverband, and the German Institute for Economic Research, DIW.

Germany is considered a wealthy country with a high standard of living, but 16% of the population had to get by on less than 979 euros a month in 2013, the level at which the government says people are at risk of impoverishment. The number of citizens in this category has increased by seven percent since 2009, according to the federal statistics agency Destatis. In contrast, average disposable household income in the total population rose by seven percent between 2009 and 2012, the latest year for which data is available.

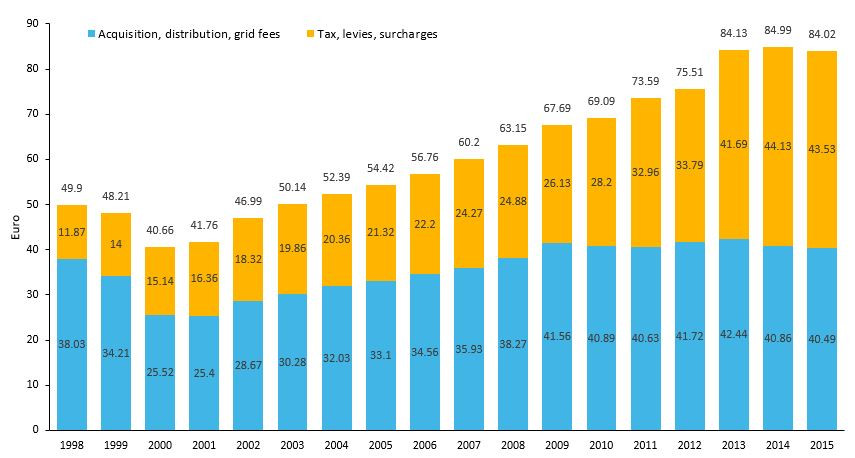

In the same period until 2013, German household electricity prices jumped 24%, mainly due to the rising surcharge Germans pay to fund the Energiewende, the transition to a low carbon economy, data from the German Association of Energy and Water Industries (BDEW) shows. In Europe, German electricity prices rank second only to Denmark. In 2014, prices eased for the first time in 15 years, but only by one euro to around 84 euros a month for a family of three, the BDEW said in April. The price comparison website, Verivox, said in April that Germans had to work 70 hours to pay for a year of electricity for one household in 2015, compared to 53 in 2005.

According to price comparison website Check24 in February 2015, welfare recipients were paying 29 percent more for electricity than was accounted for in their lump-sum monthly living cost allowance (Hartz IV program for the long-term unemployed). That was even after a government top-up at the start of 2015. “In no German state is the measurement basis for power in the unemployment benefits for Hartz IV enough to fully cover electricity costs,” it said.

Disconnected from daily life

One trigger for discussions about the effects of high power prices on the poor – sometimes dubbed Energiearmut or fuel poverty – have been high numbers of power disconnections. The network regulator, Bundesnetzagentur (BNA) began collecting data in 2011 in response to an EU directive aimed at consumer protection in the energy sector. In December, the BNA said some 345,000 consumers were disconnected in 2013, up almost 10 percent over 2011. In a country of 82 million people, seven million households received disconnection threats. Many of those simply forgot to pay their bills, but it raised the question how many people could no longer could afford to pay their power bills.

The EU energy regulators ACER and CEER said in their 2013 European gas and power market report that disconnection rates were higher in Germany than in many other countries surveyed in 2013, including Austria, Hungary, Ireland, Belgium, Luxembourg, Italy, Lithuania and the UK. Only Slovenia, Slovakia, Romania, Greece and Portugal fared worse. But some of these figures are hard to compare because of differences in national definitions and rules.

Jochen Hohmann, head of Germany’s BNA federal networks agency, noted in a speech last year that the country’s annual disconnection rate was less than one percent of all households. But he also said that “in view of the meaning of electricity and gas supply for daily life, that number is still quite high” and vowed the BNA would “use its resources to protect consumers.”

What is to be done?

In contrast to Germany, some countries like the UK, France and Ireland, have defined fuel poverty and taken specific policy measures to address the issue. In Germany, there is currently no push to address the issue directly, as many politicians believe the country already has adequate social programs in place. This makes it not only hard to know just how many people are in danger of being overburdened by their power bills, but also difficult to address the topic as a policy issue. This is why the environmental research centre IASS has called for a “fuel poverty commission” to define “acceptable limits for private households”.

In December, the German parliament debated the issue of disconnections when left-of-centre parliamentary opposition group Die Linke submitted a proposal to ban power disconnections. Government coalition members rejected this, saying power companies had a right to be paid for their services, a position the VZBV consumer group agrees with. But several Social Democratic Party (SPD) members noted that more could be done to help people on the fringes of society.

“We have to make sure that people are not left alone, that they are not overwhelmed by staying in contact with the agencies and that they have direct contact to energy providers and social services agencies,” said Markus Held of the SPD.

In reality, however, many people who are warned of impending disconnection do not know their rights or how to get a fair hearing, says Thomas Schlagowski of the Association of Energy Consumers in Unkel. They need outside help and advice to deal with the problem.

Yet companies can’t just switch off the lights at will. According to German law, once a warning is sent for an overdue bill exceeding 100 euros, a customer has two weeks to pay. After that, the power company must give a 3-day notice and check that the customer does not fulfill exemption criteria. These include small children, pregnancy, disability, illness, or old age, as well as the danger of freezing pipes, potential health hazards, or a threat to livelihoods because - for example - people work from home. If customers show they can pay in a reasonable time, they can avoid a cut-off. But it’s up to the consumer to deliver proof. “Power companies do not have to check if people have small children,” says Kaspers at the VZBV. “It is up to the individual to prove this.” The VZBV wants lawmakers to raise the arrears level, set at 100 euros in 2006, when power prices were much lower.

Do current laws offer sufficient protection from disconnections?

When reforming the Energy Economy Law in 2011, the Economics Ministry said existing welfare laws adequately protected low-income households. The help offered to these was “targeted” and “sufficient,” it said, citing strict conditions for cutting off customers’ electricity, also designed to protect the aged and infirm.

Article 35 of the 2011 German Energy Economy Law also requires the BNA federal network regulator to monitor “complaints of domestic customers, and the effectiveness and implementation of consumer protection in the area of electricity.” The BNA offers a consumer hotline and information about the law on its website, but very little in the way of easy-to-find, hands-on tips – like who is protected from disconnection - on its website for the 7 million people who received cutoff threats in 2013 and might need quick advice. This is covered by social services and independent consumer advocacy groups in Germany.

In contrast, the UK’s Ofgem, the consumer protection arm of the Gas and Electricity Market Authority (GEMA) lists practical advice for consumers and explicitly states what power companies are and are not allowed to do, such as the fact that suppliers cannot disconnect vulnerable people between October 1 and March 31. France and Belgium have similar bans. In addition, Ofgem has an ongoing dialogue with consumer groups and power companies and suggests improvements to the government.

ACER and CEER say the UK has the lowest number of disconnections in Europe, at less than 0.1% of households, due in part to “strong disconnection protections for vulnerable customers.” But while the UK officially had only 550 power disconnections in 2013, the country also relies heavily on prepaid electricity metres, an option Germany is also considering expanding. These help people manage debt and encourage efficient energy use, but also mean consumers “self-disconnect” when they don’t feed the meter. These people then lose power – lasting anywhere from hours to days, the UK national consumer group, Citizens Advice, says. They estimated as many as 1.6 million gas and power self-disconnections in 2014, many in homes with small children.

What Germany needs, says SPD parliamentarian Markus Held, is a mechanism that ensures providers deal appropriately with consumers in danger of losing power. “We need a legally mandated reporting responsibility for power providers. If one can get involved early enough, the worst can be avoided,” he said.

Slashing the bills

Many advocacy groups and experts say more should be done to avoid the threat of disconnection in the first place, mainly by alleviating the burden on the poor from electricity costs. There are two main approaches: Either finding ways to slash power bills or giving people more money to pay it.

Merely switching suppliers can cut bills by as much as 250 euros a year for an average household, the DIW said in its report. Conveying such advice is key to helping the poor, says Thorsten Kasper, energy expert at the consumer group VZBV in Berlin. If more customers used this option, this would increase competition among suppliers and create larger incentives for price cuts, a study by Energy Brainpool for Agora Energiewende argued. There should be room for improvement, as the profit of basic service providers is likely to have risen considerably between 2010 and 2013, the study estimated.

But according to the VZBV, for example, switching to a cheaper power provider can be difficult for those in arrears, because power companies scrutinize potential customers’ financial situations. Once power is disconnected, customers may have to pay as much as 200 euros, in addition to overdue bills, to have it switched back on, the group says.

In order to help low-income customers save energy and cut costs, the VZBV has started several projects with utilities, and also supports the Federal Environment Ministry’s nationwide efficiency project, StromSpar-Check, together with welfare and climate groups. The DIW also suggested more tailored advice and financial assistance on energy efficiency in its 2012 report about the Energiewende’s effect on the poor.

Another idea is to exempt a basic volume of power consumption, like the first 500-1000 kilowatt-hours used, from the current electricity tax. This would help all customers, but would affect a larger share of monthly usage for income-weak households, the DIW says, which would help cushion price rises. A 1000 kilowatt-hour tax break would compensate for 39 percent of the additional costs from the rising Energiewende surcharge in the bottom income segment, for example, DIW said.

Like the VZBV, DIW and IASS also favour adapting benefits for welfare recipients to better reflect changing prices. According to DIW, the manageable cost of protecting the poor with additional advice, welfare adaptions and tax cuts could be paid for with the taxes on the renewables levy alone. “Even if all three options are pursued in parallel, costs for public budgets are in line with revenue from VAT on the EEG surcharge, which is expected to increase to around 1.4 billion euros in 2013,” DIW said.