Renewable fuels will not solve aviation's climate dilemma - industry experts

Urgent action is needed around the globe to reduce aviation's often underestimated climate impact if the targets of the Paris Climate Agreement are to be met, industry experts said at a conference held in Berlin.

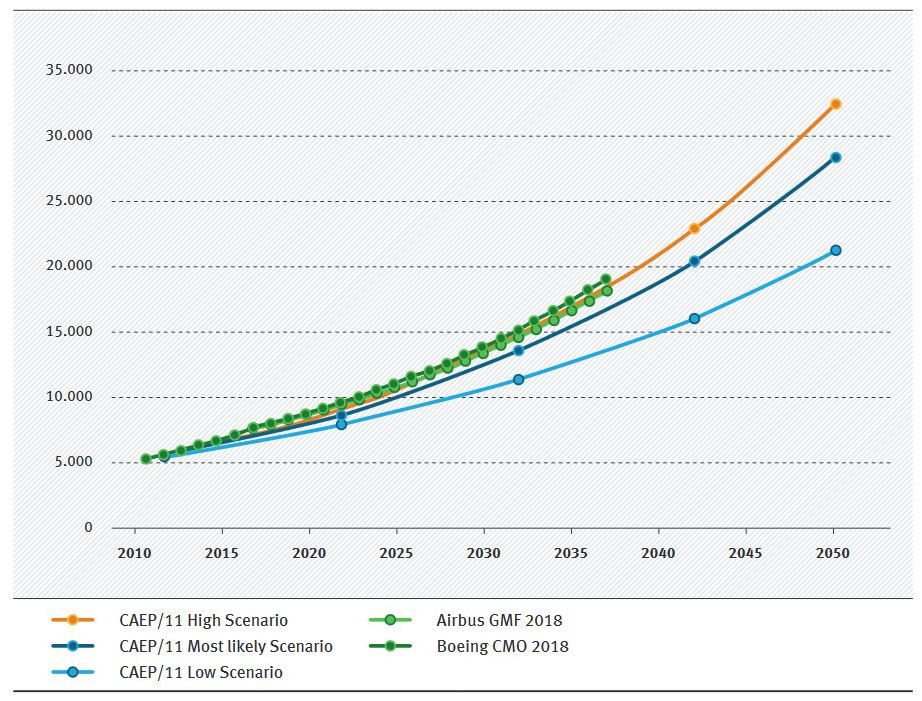

However, a number of factors make it particularly difficult to get emissions in the sector down. Experts singled out strong growth rates – current projections assume passenger kilometres will grow world-wide almost five percent per year –, the severe climate effects unrelated to direct CO2 emissions and caused by condensation trails and many other factors, and the need for international agreements.

"Aviation is probably the most difficult sector on the way to reaching the targets of the Paris Agreement," said Jürgen Landgrebe, head of the climate division at Germany's Federal Environment Agency (UBA), which hosted the conference.

No silver bullet

Conference participants were in broad agreement that synthetic fuels made with renewables are key for significantly reducing aviation's direct CO2 emissions. But they also warned that the technology, which is often referred to as "power-to-liquid" and does not yet exist on an industrial scale, is no silver bullet.

"A single solution simply does not exist," said environment minister Svenja Schulze. "We need a whole range of measures," she said with reference to taxes and other economic incentives to push the transition, emission reduction limits, quota for renewable fuels, and shifting to alternative modes of transport.

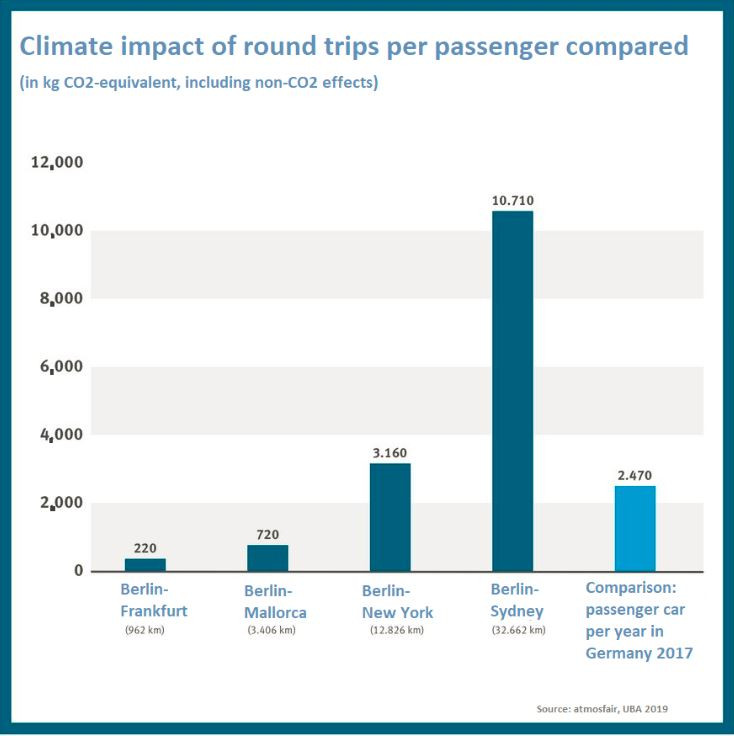

The measures mentioned by Schulze mirrored the recommendations of a new study published by the environment agency. It recommended raising existing taxes and introducing them for kerosene, replacing domestic flights with rail travel, and supporting climate-neutral fuels. At present, air traffic taxes only amount to one tenth of that levied on other modes of transport in Germany despite air traffic's status as the most climate-damaging mode of transport, the UBA said.

"We have to build up a market for power-to-liquid. But we can only provide the initial impetus, and won't be operating international production facilities," Schulze said, adding that building up an infrastructure for renewable fuels required international cooperation and treaties.

"I'm worried that we won't have enough renewable fuels," Schulze said, adding that huge demand was also expected from the chemical and steel industries, where no alternatives existed to reach CO2 neutrality.

In its study, the UBA recommended extending public support for developing power-to-liquid installations in Germany and abroad, because the country will very likely have to import large quantities of the green fuel in the future. It also proposed binding quotas for adding a climate-neutral alternative to the kerosene used today. By 2030, ten percent of aviation fuel should be sustainable, the UBA said.

The experts cautioned that using green fuels will push up demand, because people will fly more if they can do it with a cleaner conscience – a phenomenon known as a rebound effect, which might sharply reduce green fuel's positive effects.

Sustainable aviation academic Stefan Gössling from Sweden's Linnaeus and Lund Universities pointed out that not all countries were as focused on renewable fuels as Germany. "Norway focuses on battery electric planes, the UK on hybrid electric models with biofuels, and Sweden on biofuels."

Gössling also cautioned that betting on future technologies to cut emissions is an open invitation to postpone tackling the problem by other means today – for example by flying less.

Non-CO2 effects mean "there will never be a truly climate-neutral flight"

Focusing on power-to-liquid also posed the risk of neglecting the very climate-damaging side-effects of flying, which are unrelated to CO2 emissions – such as condensation trails, particles and other greenhouse gases emitted at high altitudes, conference participants warned.

The UBA said these so-called "non-CO2 effects" likely harm the climate twice as much as direct CO2 emissions, according to most estimates. However, these are ignored by many industry lobby groups and the UN's International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), according to the UBA.

It also remains an open question how exactly to deal with these effects, according to industry experts.

"We still have no solutions for the non-CO2 effects," the UBA's Landgrebe said. In its study, the UBA said both aviation's direct CO2 emissions and the non-CO2 effects should be integrated into the European Emissions Trading System (ETS).

Atmospheric scientist Robert Sausen from the German Aerospace Center (DLR) said it might be possible to halve aviation's non-CO2 effects on long-distance flights in the longer term. These effects depend strongly on weather conditions, altitude, time of flight, and countless other factors.

"There will never be a truly climate-neutral flight," Sausen said.

- Stiopa](https://www.cleanenergywire.org/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_image/public/contrails.jpg?itok=RidrDjeh)