A power grid fit for a clean energy future

Content

Bottlenecks create a north-south divide

Objections and delays

A subterranean solution

“Fantastic returns” for grid operators

Transmission vs. decentralisation

Pegging renewable expansion to grid expansion

The dream of a single European power market

A more intelligent power system

Updating the low-voltage networks

As much grid as necessary, as little grid as possible

There are few countries in the world where months of wrangling to avert what the president called the “worst governing crisis” in the Federal Republic’s history, might result in a hard-won coalition that ranks building new high-voltage power lines among its biggest priorities. All the more surprising, given the country in question is not an emerging economy stunted by a under-developed power system, but Europe’s biggest industrial economy, with one of the world’s most secure and stable electricity supplies.

Yet for all the issues competing for attention, the Energiewende – Germany’s dual move away from fossil fuels and nuclear power in favour of an energy system based almost entirely on renewable sources – is a key policy project of successive governments. And it has hit a major hurdle.

The energy transition’s big success to date is the rapid growth of renewable power generation, which covered 36 percent of German power consumption in 2017 – up from 3.2 percent in 1991. But the biggest share of this is from wind power, mainly generated in the country’s north, and in order to make proper use of it, the electricity grid has to be up to the job of transporting it to where it’s needed – in particular the industrial south and west of the country. Right now, it isn’t, and that’s putting the brakes on further expanding renewable capacity – which should be accelerating if Germany is to reach its targets for cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

“The Energiewende will succeed if we make progress with the grid extension,” Germany’s new Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Energy, Peter Altmaier, said simply, in his first speech to parliament in March 2018.

So far, the grid has remained stable. But imbalances in the system and inflexible conventional power generators mean keeping it that way is costing the country close to one billion euro each year. And with Germany’s last nuclear power stations scheduled to shut down over the next five years, there will be ever-more demand for northern wind thousands of kilometres from where it’s produced.

While some still argue that a more radically decentralised power system could avert the need for new high-voltage cross-country connections, there is a consensus between government, the grid regulator and most experts that the infrastructure is needed – and fast. The European Commission is piling on the pressure too, threatening to split Germany into two power-market bidding zones if bottlenecks aren’t resolved by 2025.

Yet public protests against power lines near residential areas have bogged the project down in disputes over where the new power lines should be located. Minister Altmaier has pledged to tackle this problem. “I promise you that after six months in office, I will know every problematic line personally and have visited it,” he told the Bundestag.

But the profits of grid operators – some of them belonging to ailing large utilities such as RWE and E.ON – stand to make from expanding the system have also raised suspicion over whether development on this scale is really needed.

And there are further challenges on the horizon. It’s not just the big transmission lines that need major development. Researchers say the vast and long-overlooked network of low and medium voltagedistribution grid must be updated in the coming years for a modern, interconnected energy system that incorporates storage capacity, power-to-x facilities and electric cars, as well as fluctuating renewable power generation.

Beyond that, it is still unclear whether more power lines than currently planned will be necessary as more and more renewable power is generated, or if existing capacities might be sufficient if better utilised by a “smart” automated system.

Bottlenecks create a north-south divide

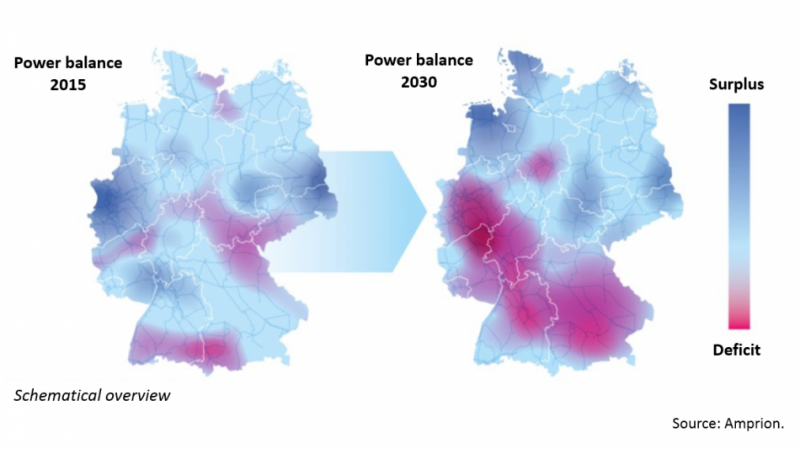

In 2017, 33.3 percent of German power production was from renewable sources – 13.5 percent onshore wind, 2.7 percent offshore wind and 6.1 percent photovoltaic (PV) solar. Over two thirds of Germany’s onshore wind capacity is installed in the northern and north-eastern states of Schleswig-Holstein, Lower Saxony, Mecklenburg Vorpommern, Brandenburg and Saxony-Anhalt. Meanwhile, large metropolitan areas and power-hungry industry are largely located in the south and west of the country.

Over the course of a year, the northern state of Schleswig-Holstein produces more power than it can use itself, while the Bavarian state government warns that it will face a 3-gigawatt (GW) capacity shortfall once the last nuclear power plant has gone offline in 2023. “With the growth of renewable power sources, we see a drifting apart of generation and consumption centres,” Jochen Kreusel, head of the Market Innovation of the Power Grids Division at ABB, one of the world’s biggest suppliers of products and solutions for power systems and grid management software, told the Clean Energy Wire CLEW.

Source: Amprion Netzausbau.

The 35,000 kilometres of transmission lines currently linking the north and south of the country were never intended to carry so much power. On particularly wind days, huge volumes of cheap renewable power flood the electricity market, pushing down the wholesale power price and encouraging customers in southern Germany (and Austria – as the two countries are currently part of a joint power market) to buy more. But the wind power cannot be transported to these customers, so grid operators must quickly call on power stations in the south to generate power and pay above-market rates for it. Between 2014 and 2015 the volume of these “re-dispatch” measures rose more than threefold. [See factsheet re-dispatch].

At the same time, renewable power production in the north has to be curbed because it doesn’t have anywhere to go. This “feed-in management” incurs further costs because wind power producers must be compensated when their turbines are switched off.

Other reasons for re-dispatch are too high amounts of conventional power blocking the grid, and exceptional events such as an increase in electricity demand in France, Italy, Austria and/or Switzerland due to low water levels in hydro power plants or safety shut-downs of nuclear power plants.

Re-dispatch and feed-in management costs amounted to 880 million euros in 2015. They fell to 593 million euros in 2016 – a less windy year – but are expected to have risen again in 2017. In Schleswig-Holstein alone, where 72.3 percent of feed-in management measures were taken in 2016, these costs amounted to 273 million euros.

Transmission grid operators calculate that such grid stabilising measures were needed on 329 days last year. The completion of the Thüringer Strombrücke connection between Saxony-Anhalt and southern Germany brought some relief to the transmission grid zone administered by grid operator 50Hertz in the East of the country, and lowered its re-dispatch costs in 2017. But other bottlenecks remain, and will likely see costs rise to over 1 billion euros for re-dispatch and feed-in management every year.

Thomas Wiede, head of communications at transmission grid operator Amprion, told the Clean Energy Wire things would only get worse when south Germany loses its nuclear capacity in 2022. “Without the grid expansion this will lead to even more interventions to ensure grid stability and higher costs for everyone,” he said.

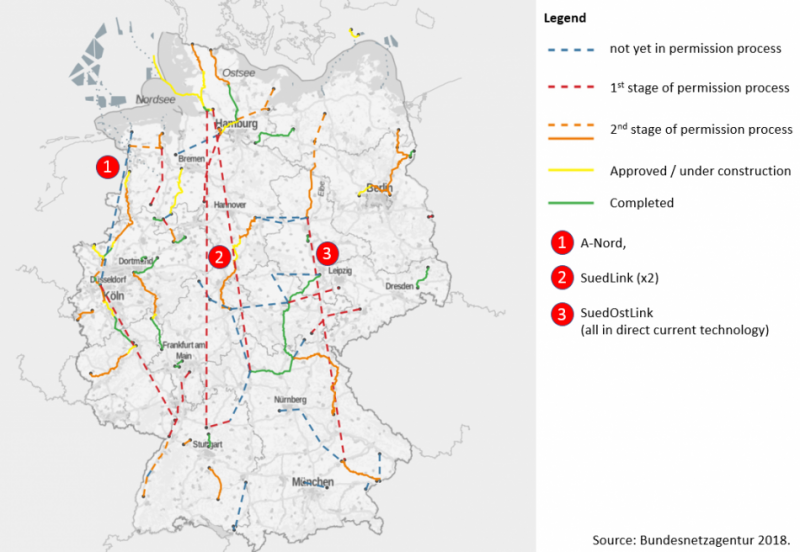

The solution backed by transmission grid operators and federal government is accelerated construction of more north-south power lines. A total of 4,650 kilometres of new transmission power lines are supposed to be ready by 2025, including four north-south connections built as direct-current high-voltage lines. So far, 900 kilometres have been built.

Source: Bundesnetzagentur 2018.

Objections and delays

Transmission grid operators have tentatively begun to warn that completing these lines by 2025 is looking doubtful. “Seen from today’s perspective, we’re on schedule. But the biggest hurdle lies still ahead,” Boris Schucht, CEO of transmission grid operator 50Hertz, said in March 2018. In the area administered by 50Hertz, 53.4 percent of the power produced is from renewables. Depending on legal challenges to planning permission from anti-grid expansion initiatives led by citizens and environmental organisations, the power lines 50Hertz is planning to complete by 2025, could be delayed by up to two years.

The average time it takes a large power line to get through planning and construction in Germany is about 10 years. “There is no other country in Europe that struggles so much with completing new infrastructure projects, and where they take so long,” Götz Fischbeck, Head of Smart Solar Consulting, told the Clean Energy Wire. “Everybody wants the energy transition but as soon as it could change something within their field of vision, they oppose it.”

State-level politics, while officially backing the goals of the energy transition and grid expansion, aren’t always helpful either. In 2014, the then Bavarian State Premier Horst Seehofer responded to citizen groups’ protests against power line plans near their villages by questioning the need for north-south grid connections, suggesting that new gas fired power stations in the south could solve the problem instead. In March 2018, Thuringia’s State Premier Bodo Ramelow announced that his state would take legal action against the proposed route of SuedLink power line through his state, saying a more direct cable could be laid through neighbouring Hesse. Hesse opposed the idea, and, in January 2018 so did the grid regulator the Federal Network Agency (Bundesnetzagentur). Thuringia threatened to sue. “It is absolutely counter-productive that state politicians oppose the central infrastructure of the Energiewende,” Stefan Kapferer, head of energy industry association BDEW, said.

A subterranean solution

Oliver Brückl, professor of electrical engineering and IT at East Bavarian Technical University Regensburg, believes better communication could overcome public protest. “The problem is that citizens have often not received sufficient information regarding the alternatives to the grid expansion and that politicians don’t contribute sufficiently to the understanding why grid expansion is necessary,” Brückl told the Clean Energy Wire.

Brückl has spoken to communities where new power lines are planned and says there are arguments that win citizens over. “I always focus on the alternatives for one particular power line. In Bavaria, those would be securing supply through gas power plants, importing electricity from abroad or increasing renewable capacity and building big long-term storage facilities.” Each of these options comes with an additional price tag of between 1.5 and 6 billion euros per year, compared to building the power line in question, Brückl calculates.

In a bid to boost acceptance of new grid connections, in 2015 the federal government decided to prioritise new technology allowing cables to be laid underground. The four large north-south direct current lines of the A-Nord, SuedLink and SuedOstLink projects will be mostly subterranean, even though this will push the cost up by between 3 and 8 billion euros, and parts of the planning process had to be restarted.

One reason why high-voltage underground cables are expensive is that the technology has only been used in a few, exceptional cases, Kreusel from ABB said. “Now, thousands of kilometres of underground cables are going to be built – that means there will be learning effects and scaling effects, and an innovation push,” Kreusel said. He added that even with underground cables, grid expansion made economic sense compared to re-dispatch measures.

So far, the protests indeed seem to have died down somewhat since the government decided the power lines would be buried. But they won’t be completely hidden because trees cannot grow above them. Farmers have voiced concerns about the usability of fields under which cables are buried, and have asked for annual compensation payments. Once the exact routes of the new lines are defined, further objections are expected.

“Fantastic returns” for grid operators

Another reason for scepticism over new grid projects in general is the assumption that grid operators, who are responsible for proposing grid expansion projects that are then checked by the Federal Network Agency, have an economic interest in building more power lines.

Consumer organisation VZBV says grid operators receive “fantastic returns” on their investments in grid expansion. Because Germany’s big utilities – E.ON and RWE in particular – are struggling with the energy transition and have seen their earnings from power generation dwindle, the regulated grid business has become a much-needed cash cow. When, in March 2018, RWE and E.ON announced they would split RWE spin-off innogy between them, analysts applauded E.ON for getting its hands on the most valuable aspect of innogy’s business – distribution grid operations.

“It’s obvious that grid operators are market players who benefit from the grid expansion,” consultant Fischbeck said. “We have a regulatory system that guarantees grid operators a fixed return on their capital expenditures on grid expansion, whereas other options that could potentially reduce the need for new power lines and be more cost efficient overall – such as power storage or electrolysers – do not offer the same financial benefits.”

Paul-Georg Garmer, head of public affairs at transmission grid operator TenneT, disputes the idea that building redundant infrastructure is in grid operators’ interests. “Of course grid operators have to generate returns, but we also want to avoid stranded investments,” he said at an event organised by the Renewables Grid Initiative (RGI) (an alliance of grid operators and environmental groups) in Berlin in March 2018. “If we build something that after ten years stands around unused, we’re not generating those returns.”

Compared to other regulated sectors such as water or telecommunications, grid operators’ returns are pretty average, Wiede at Amprion insists. “If they dropped distinctly below that, it would become hard to reason that investments in the energy transition project are economically viable,” he told the Clean Energy Wire.

A court in Düsseldorf has backed the grid operators’ position, ruling that the Federal Network Agency in fact set fixed return rates for capital investments in power lines too low when it reduced them from 9.05 percent to 6.91 percent in 2016. The grid regulator is now likely to set a figure somewhere between the two.

Transmission vs. decentralisation

Buried cables and business interests aside, there is a more fundamental argument against large-scale grid expansion. Activists and a sector of the scientific community believe the Energiewende should result in a decentralised power system.

“All the large technical solutions benefit first and foremost big companies. We want an energy transition that is done by the people,” Hartmut Lindner of the Schorffheide-Chorin “No overland power lines through the biosphere reserve” citizen initiative, said at the Renewables Grid Initiative event in March.

Proponents of a decentralised, cellular, system argue that it would significantly reduce the need for new, long-distance power lines. A combination of renewable power plants (mainly wind and solar PV) and power storage could be installed close to consumers and make whole regions self-sufficient.

However, studies suggest that while this might be possible for rural communities, it isn't realistic in larger urban and industrialised areas. “It is clear that we have a lot of technical options in the future, but we also have to be honest and say that there will be trade-offs, such as high costs for storage and using up land for renewable installations,” Felix Matthes from the Institute for Applied Ecology (Öko-Institut), lead author on a recent meta study on regional power grids, said. “Those who say we don’t need power lines from north to south also have to say how much onshore wind power they will accept in the south.”

According to the Öko-Institut study, which was commissioned by Renewables Grid Initiative and NGO Germanwatch, the realistic potential for onshore wind power in southern Germany and near the big metropolitan areas is limited – particularly when taking into account that wind turbines in these regions have been, like grid extension, met with public resistance. The study’s authors conclude that even a decentralised system would require the planned grid expansion.

Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND) concedes that even a decentralised energy system will require grid expansion, but not to the degree currently set out by the national Grid Development Plan (NEP). “We are convinced that we need energy generation in close proximity to the consumer, and we know that that means wind turbines in forests,” Thorben Becker from the BUND’s climate action team said. Becker argues that as the energy transition progresses, new wind parks can be expected to provoke public protest in the north just as they would in the south.

Pegging renewable expansion to grid expansion

The good news is, so far, existing grid infrastructure is bearing up. Grid operators, previously accused of crying wolf over blackouts, now boast they can keep the grid stable despite the growing proportion of power produced from renewable sources. The average time a German consumer spent without power in 2016 was 12.8 minutes (excluding exceptional events), compared to 128 minutes in the US (2016), 53 minutes in Great Britain, 92 minutes in Greece, 54 minutes in Spain, 41 in Italy, 50 in France and 191 in Poland (2014 data).

But the German grid will need to cope with far more fluctuating, renewable power in the future. “The new power lines that we are talking about now, are those that are necessary to enable us using the renewables power we already have,” Kreusel said.

The long-term goal of the German energy transition is a system based almost entirely on renewables. To this end, the government drew up its Climate Action Plan 2050, outlining the massive decarbonisation of all sectors of the economy aimed at an overall CO2 emissions-reduction of 80 to 95 percent, compared to 1990 levels. So far, renewables have only really penetrated the power sector, and emissions aren’t falling fast enough for the country to hit its targets.

In 2018, the new government upped its target for renewables, to cover 65 percent of German power consumption by 2030. The most obvious source of all this extra renewable power is more turbines in the country’s windswept north. “If most of this new capacity is built in the north, the grid as we plan it now will not be able to transport the power,” 50Hertz CEO Boris Schucht said in March 2018.

The government is aware of the problem and has included a provision that renewables expansion is to be “synchronised with the grid expansion” in its coalition treaty – effectively meaning it can default on its 2030 target if the grid isn’t up to the job of integrating all that new renewable power. Even tenders to add 4GW each of onshore wind and solar PV capacity to the system by 2019 and 2020 are subject to the “carrying capacity of the grid”.

That has led to widespread fears that much-needed renewables expansion will stall, and the country will fall further behind its CO2 reduction targets. But Fischbeck says these measures are necessary to rationalise the system. “We still have the anarchic situation that everyone can install a wind, solar or biogas plant wherever they want, without anyone asking whether the power is needed there and whether it fits into the grid topology,” he told the Clean Energy Wire.

The dream of a single European power market

The federal government wants grid connections built, and fast; affected citizens want them built elsewhere; electricity consumers don’t want massive investments in the grid to push up their power bills. And there’s pressure from outside Germany, too.

In its quest for an internal European market for electricity (See the energy winter package of 2016: Clean Energy for all Europeans), the European Commission is breathing down the necks of Germany’s government and transmission grid operators, because bottlenecks in the German grid also interfere with European power trading.

Meanwhile, Germany’s neighbours complain that its grid congestion is resulting in unwanted surges of power through their networks, or blockages at the borders. “Germany is currently pushing its internal grid capacity problems towards the borders, and we have to do something about that,” Klaus-Dieter Borchardt, director for the internal energy market at the Directorate General for Energy of the European Commission told the Clean Energy Wire.

In 2017, the Commission threatened to split the German power market into two bidding zones because the internal blockages clearly prevented the delivery of northern (wind) power to consumers buying it up in the south. The German government objected strongly to the move – which would have seen power prices rise considerably in the country’s south – leading to a compromise which will see the price zone split along the German-Austrian border from autumn 2018.

Jochen Homann, head of Germany’s Federal Network Agency (Bundesnetzagentur) doesn’t appreciate pressure and criticism from Germany’s neighbours and the EU. “Germany’s energy transition, which is now causing us grid problems and additional costs, has pushed down electricity prices for the whole of Europe,” Homann said at a BDEW grid conference in March. “One could also consider whether it’s fair to let Germany bear the costs alone.”

In its 2018 coalition agreement, the German government reiterated that it intends to “adhere to the target of a single power bidding zone in Germany.”

A more intelligent power system

New cross-border connections to Norway and Belgium could provide the German grid with some relief until internal power lines are completed in the second half of the 2020s.

In the meantime, government and grid operators are working on other ad-hoc technical fixes – overhead line temperature monitoring, phase-shifters, re-dispatch optimisation or flexible alternating current transmission systems (FACTS) – aimed at making the grid smarter, more flexible and more responsive. In Schleswig-Holstein, distribution grid operator HanseWerk is developing an online platform, where power producers and consumers can trade directly, adjusting supply to demand and helping keep the grid stable.

According to the Ministry for Energy and Economic Affairs (BMWi), such digital solutions could free up grid capacity, and reduce costs over the next few years. “We are looking at a cost-saving potential of around 200 million euros per year,” Alexander Folz, in charge of the SINTEG programme at the BMWi said in January 2018.

Folz added that these measures would complement, rather that provide an alternative to, grid expansion. But in the longer term – from 2030 on – improved technology could see digitalisation replace the need for an ever-expanding high-voltage network – even as electricity demand grows to accommodate the next stage of the energy transition.

If integrating excess wind power into the existing grid is today’s challenge and dealing with a 65-percent renewable power supply tomorrow’s, then building a grid for an “all-electric world” is the ultimate goal. “We’re at the beginning of an all-electric world. All sectors I can imagine will be electrified, even if only indirectly,” professor Armin Schnettler, senior vice-president of energy and electronics research at Siemens AG and head of the institute for high voltage technology at RWTH Aachen, said in March 2018.

So far, Germany’s energy transition has in fact been an electricity transition, with little progress made on switching to renewables in the rest of the energy system. If the country is serious about its national target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 80 to 95 percent by the middle of this century, all sectors, including transport and heating, need to be based on renewables. The plan is to achieve this through sector coupling: Using renewable power to drive cars, and power-to-x technologies to convert it into clean fuels – such as hydrogen and synthetic gas – to heat homes and fuel lorries.

“It’s not clear yet whether this sector coupling will lead to more or less pressure on the grid,” Brückl said. Switching from fossil fuelled cars to electric ones could raise German power demand to 914 terawatt-hours (TWh) per year by 2050 (compared to 516 TWh in 2016), according to Agora Verkehrswende*. If 30 percent of Germans drive e-cars and plugged them into recharge as soon as they got home from work, the low voltage grid would very likely collapse, consultancy Oliver Wyman warned in a recent study. But if managed right, this extra demand could help balance the grid, providing an outlet for excess power.

Updating the low-voltage networks

Germany’s 1,679,000 kilometres of distribution grid – which supply electricity on the low and medium voltage level to households and companies everywhere, and to which 98 percent of renewable power production capacity are connected – need to be smarter, so information about power production and consumption can be used to better balance supply and demand. “It’s embarrassing that Germany hasn’t managed a smart metre rollout in the past eight years,” Thomas König, CEO and CFO of power grids at E.ON, said.

Since the rollout of wind and solar installations across Germany’s fields and rooftops, the role of distribution grid operators has evolved from that of mere suppliers. With more than 1.5 million renewables installations feeding into the distribution grid, power now flows in both directions. “This makes the grid both more complex and more flexible,” Patrick Wittenberg, head of strategic grid economics at innogy, told the Clean Energy Wire.

But large investments must be made to make use of the flexibility, i.e. the ability to balance power consumption and demand and thereby stabilise the grid. “The lower the voltage level the less information and communication technology has been installed in the past. That means that today the grid mainly cannot be observed online and in real-time,” Wittenberg explained.

What’s needed are smart metres and local distribution substations, accurate weather forecasts, and a lot of new grid management technology and software. According to industry association VKU, these investments should amount to over 25 billion euros in the next ten years. Many minor regulations and market conditions have to be adjusted, grid operators and researchers say.

“We have too few incentives for intelligent grids in Germany. IT investments receive much less compensation than copper [for building power cables],” 50Hertz CEO Boris Schucht said.

Part of the challenge is the sheer number of players involved. In contrast to the transmission grids, which are in the hands of four large operators, there are over 800 distribution grid operators in Germany. Some belong to bigger companies like E.ON, innogy or EnBW, but others are run by small local utilities. [See Factsheet Setup and challenges of the power grid].

“Distribution grid operators have been treated as an afterthought in recent years, now it’s recognised that the key activity of the energy transition is primarily in the distribution grids,” E.ON’s König said.

As much grid as necessary, as little grid as possible

Whether Germany will need even more grid expansion after 2030 is a controversial and as yet unanswered question. “I doubt that we will travel the republic again after 2030 and tell people that this was only half of the extra grid that is needed,” Patrick Graichen, head of think tank Agora Energiewende* said at a grid conference in Berlin in January 2018. Jochen Kreusel and Oliver Brückl are more circumspect, saying it’s too early to make such promises. But all three agree that post-2030, increased flexibility and new technologies to make better use of the existing grid must be prioritised over grid expansion.

The idea that as little grid should be built as possible has to be a leitmotif, Antina Sander, deputy executive director of the Renewables Grid Initiative, said at the presentation of the Öko-Institut study in March. At the same event, Thomas Dederichs, senior politics expert at innogy, warned that grid operators had to keep in mind that other technology could sometimes trump further grid connections. “If there can be local storage units that store the lunch-time solar PV power peak until it gets used in the evening for 1 cent per kilowatt-hour, it doesn’t make sense to build grids that transport this power for 8 to 9 cents per kilowatt-hour.” He added that, in the end, the most publicly acceptable solution could be better than the most cost-effective.

Still, the majority of researchers, politicians and grid operators (see scenarios by 50Hertz and TenneT) agree the transmission lines currently planned will be essential to deal with the volume of power expected to be coursing through the grid by 2030. “We’re seeing in the studies that expanding renewables considerably in the south and west could maybe reduce grid expansion up to 2030 but if we’re looking at a world with 85 percent renewables after 2030, we would need the power lines anyway,” Matthes of the Öko-Institut said.

And the grid faces a major test before then. If lagging grid development now threatens to stall the growth of renewables, it could soon put the other pillar of the Energiewende in jeopardy. In 2022, Bavaria’s Isar 2 nuclear power plant, which supplies 11 million megawatt-hours, or 12 percent of the state’s power, is slated to shut down, ushering in Germany’s post-nuclear age. “If this happens before the grid is improved, we will be quite close to the abyss,” Brückl said. “I’m not sure if they will be brave enough to actually switch off Isar 2.”

*Like the Clean Energy Wire, Agora Energiewende and Agora Verkehrswende are funded by the Stiftung Mercator and the European Climate Foundation.