Patchy counselling holds German citizens back from investing climate friendly

The roll-out of Germany's energy transition depended to a large extent on industrious citizens and small commercial investors. Their venture to put money into green technology coincided with fertile political conditions that let their investments flourish. The country's trademark Renewable Energy Act (EEG) in 2000 allowed these early adopters to benefit from guaranteed returns and helped expand wind and solar power to a scale that substantially lowered investment costs for renewable energy and other transition technologies. Nearly 20 years after the renewable act's introduction, a large part of Germany’s renewable power capacity is still owned by citizens – but investing in green and sustainable projects appears to remain a passion of the few.

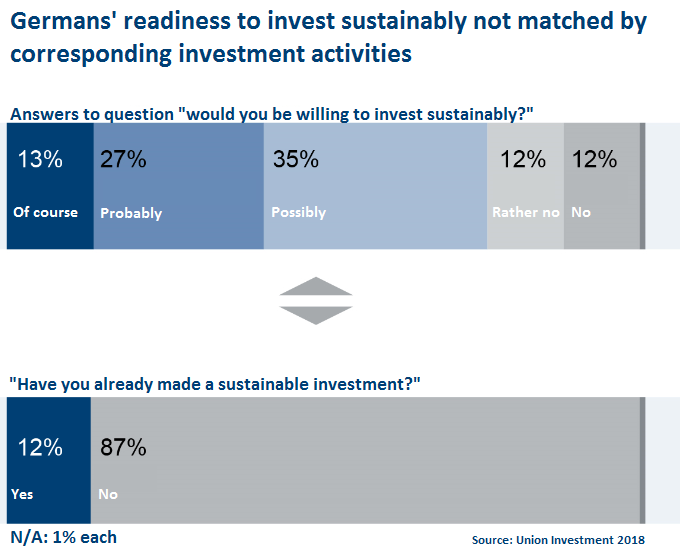

German private investors, meaning small savers and others looking for ways to gain from their private assets, have long-standing experience with and show continuously high support for the Energiewende, the parallel phase-out of nuclear power and fossil fuels and shift to a more efficient energy system based on renewable power. Nevertheless, most still do not invest in financial products that explicitly support clean technology and are managed under the so-called ESG criteria, which gauge the environmental, social and good governance dimension of investments. Only 12 percent of private investors surveyed by asset management company Union Investment said they have put money into sustainable products – even though almost half of all respondents said they think it would be a good idea.

"A lack of transparency and knowledge about the products seems to keep investors from putting their savings into it with good conscience," said Union Investment's private customer manager Giovanni Gay said in a press release. "Sustainable products have to become simpler and easier to understand to meet customer demands.” But growing concerns over global warming and falling costs for renewables have begun to trigger a change in attitude. The interest in green and sustainable finance products is growing rapidly and many private investors have done away with the notion that only financial professionals should care about the impact of investments on climate change, social justice and other non-financial aspects, the survey showed. According to investment manager Gay, sustainable finance has long ceased to be considered a "temporary fashion" for private investors and instead has become a viable alternative in times of persistently low interest rates.

The ESG criteria - sustainability for investments

In order to minimise the disruptive effects of climate change and political responses to it on financial marekts, the Paris Agreement has stipulated a harmonisation of financial flows and emission reduction targets as one of its long-term objectives. This "shifting of the trillions" is meant to happen on two dimensions: First, by ensuring that investments do not run counter to emission reductions and, second, by raising capital for climate action measures. This implies systematically drying up financial flows that clash with reduction targets as well as a set of financial market reforms, such as a mandatory disclosure of climate-related risks, “Paris-compatible” investment criteria, adequate CO2-pricing schemes, stress-tests for credit systems, cutting fossil subsidies and decarbonisation roadmaps for industrial companies.

All of these measures are comprised in the concept of sustainable finance, which aims to ensure that the full impact of investments is understood and resulting risks are weighed against potential profits accordingly. Sustainable finance typically is based on so-called ESG criteria, which gauge the environmental, social and corporate governance dimension of capital flows. From a climate action perspective, the focus naturally rests on investments’ environmental aspects and is commonly referred to under the term “green finance”.

New EU counselling rules for banks expected to trigger sustainability interest

Two factors are hampering investor interest in green and sustainable finance options. First, many banks do not regularly inform their customers about sustainable investment options, a shortcoming that the European Commission addresses in its sustainable finance action plan, which names greater transparency for investors as key necessity. With the EU’s updated Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II), asset managers will be obliged to include information on how they handle ESG-related risks and on sustainable investment vehicles in their sales documents “as part of their duty to act in the best interest of clients”. The Sustainable Investment Forum (FNG), a finance industry association that analyses green and sustainable investments in German-speaking countries, said the new EU rules are likely to quickly increase demand for more detailed counselling on sustainability aspects by financial consultants.

The second factor is the unclear definition of sustainable finance and the resulting lack of standard procedures and certifications. It is common practice to exclude companies from investment portfolios that engage in certain undesirable activities, such as producing controversial weapons or violating labour rights. But just how to deal with companies that, for example, supply weapons producers, and the promotion of better business practices, is not as clear. The sustainability principles of asset management providers like DWS, a branch of Germany's biggest commercial bank Deutsche Bank, only contain a very narrow range of exclusion criteria, meaning the bulk of its assets under management continues to fund companies that make money with war weapons or fossil fuels, for example, NGO Association of Ethical Shareholders said.

Other sustainability principles are based on so-called "best-in-class" schemes, in which companies performing better than their competitors on metrics like greenhouse gas emissions or worker protection. But this approach is more complicated and private investors may have less patience for understanding how it works. Gerhard Schick of NGO Finanzwende said such relative performance indicators lack absolute effects: "It allows practically every company to excel in some category and still gives no indication of its overall credentials", Schick told Clean Energy Wire. "If every company is still seen as a legitimate investment target, the steering effect is zero," Schick said. In order to really use the financial sector’s leverage for reaching climate targets and to promote better corporate governance in accordance with the ESG criteria, more binding sustainability concepts are necessary, Schick said.

Investors do not lack noble goals but largely ignore sustainable options

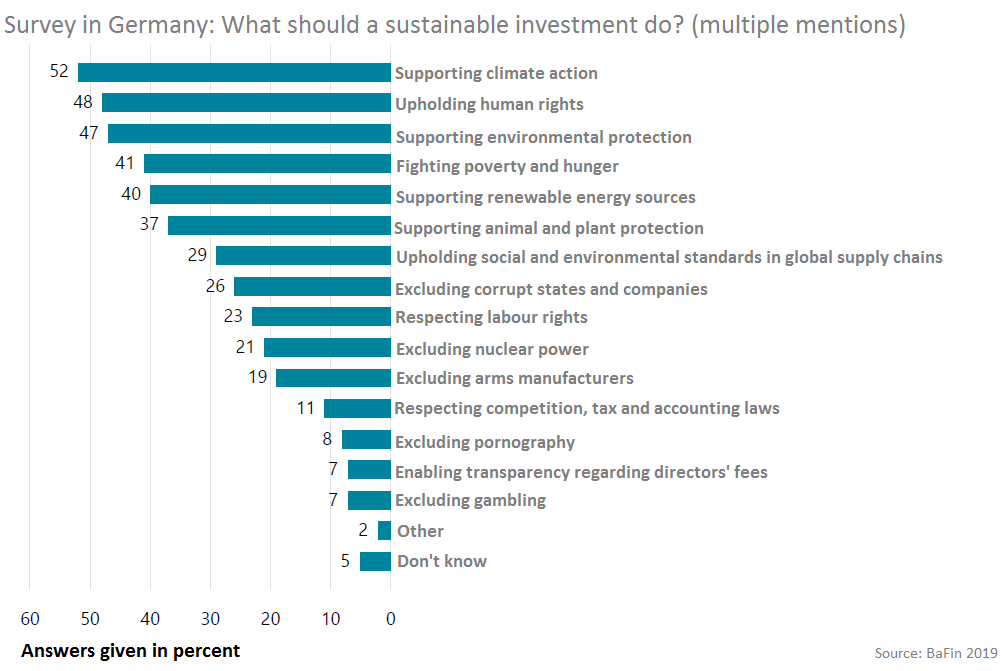

But apparently most people in Germany do not even need to be convinced of the importance of individual investment decisions for climate policy. While ESG criteria cover a wide range of topics, the environmental component has the greatest influence on investors' readiness to review their investment choices. In a separate survey by Germany's finance authority BaFin, a majority say that protecting the climate is the most important task sustainable finance has to address.

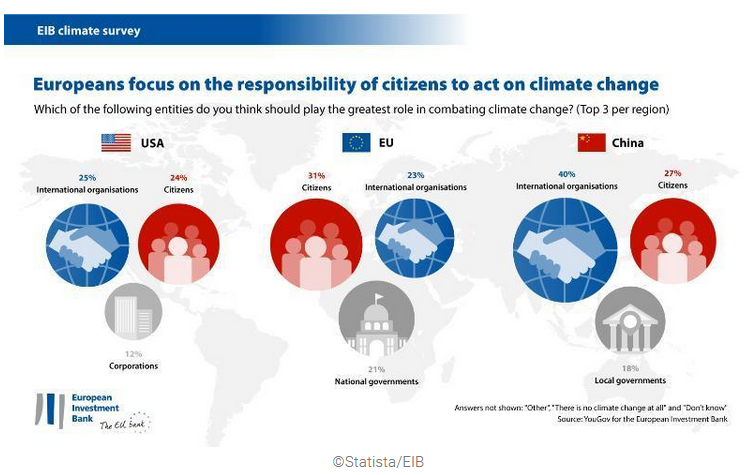

By the same token, financial consequences were most Germans’ main worry when confronted with the impact of climate change, according to a 2018 survey by the European Investment Bank (EIB). Almost half of respondents said rising costs of insurance, energy or food, and higher taxes were their chief concern over the next decade, whereas only 45 and 39 percent, respectively, said they were most worried about social challenges and health problems. However, most people in Germany and also across Europe said individual citizens bear the greatest responsibility to act against climate change.

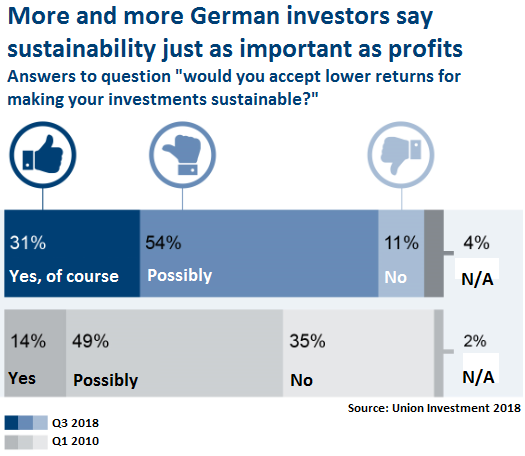

Many investors who do not want to face the difficult task of monitoring markets themselves put their assets into so-called exchange traded funds (ETFs), which passively mirror the development of selected market indices. Even though, according to the BaFin survey, about 40 percent of private investors in Germany would accept lower returns if they knew their assets were managed sustainably, this sacrifice is apparently not even necessary, as a look at the performance of sustainable investments over time reveals.

Consumer protection organisation Stiftung Warentest said while there currently are only a limited number of ETFs that implement sustainability criteria and reflect global indices, these brought sound returns that on average did not perform worse than the important reference index MSCI World over five years until 2018 – and even slightly outperformed it when looking at the previous three years only.

Investment associations warn additional regulation could suffocate existing ESG approaches

Stricter minimum standards already exist in sustainability rankings offered by specialised agencies, such as ISS Oekom, MSCI or Sustainalytics. Moreover, sustainable finance forum FNG established the country's first sustainability certification in 2015, allowing small investors to gauge the ESG credentials of potential investment targets. The certificate also promotes funds that are particularly strict in respecting the ESG criteria. However, irrespective of the individual rating's merits and accuracy, they do not offer a coherent frame of reference. The European Commission wants to streamline the multitude of existing approaches and resolve information asymmetries by creating a common European classification system of the types of investment activities available to private investors, a so-called taxonomy.

"The EU plan sets the course for supporting sustainable investments", said Thomas Richter, head of the German Investment Funds Association (BVI), which says it represents the investments of more than 20 million households. The BVI has said a better identification of risks and a clearer description of asset managers' sustainable investment goals are steps in the right direction but warned that proper customer counselling on ESG could only happen after the EU has agreed on a taxonomy. Banks and other asset managers could not be compelled to give advice on something that has not been defined yet: "The Commission should not take the second step before it takes the first one," said Richter.

In addition, Frank Dornseifer of the alternative investor association BAI warned against a "hype" around the EU taxonomy that could create more bureaucracy and smother existing approaches to implement ESG concepts. According to the BAI, there are already many sound ESG integration approaches that allow investors to act sustainably on their own initiative. "Evaluating and developing existing and globally accepted standards is much more important than re-inventing everything from scratch in the complex European legal process with all its obstacles," the BAI said.

"Especially institutional investors are much more advanced in terms of sustainable investment than one might think," Dornseifer said. He argued that sustainability could not be imposed from above through political compromise and had to be achieved by raising awareness. "It comes down to farsighted, considerate and holistic conduct by investors."

Likewise, the association of Germany's public banks, DSGV, expressed doubts about inducing "social policy developments" through regulatory law. "Ultimately, it's on people to create demand for sustainable finance products by increasing their demand for sustainable products," the DSGV said. "People need to be able to decide which combination of risk, liquidity and returns suits them most."

Financial conservativism makes Germans hard nut to crack for green finance

One possible reason why Germans nevertheless still seem to take little interest in investing in green and sustainable projects, such as the country's highly capital-intensive Energiewende, may be cultural – and also structural. There is a general scepticism towards financial speculation and preference for financial security, even at the expense of lower profits. In addition, the capital market is not as important for Germans as it is for people in many other countries, since their pensions are often covered by a pay-as-you-go system. This means funds are directly redistributed from the working population to pensioners, rather than drawing from invested capital.

"There is definitely something peculiar about Germany in this case. The four preferred options of Germans for what to do with their money are either putting it into a savings account, into a fixed-deposit account, into an overnight money account or into a building loan contract," said Christian Klein, corporate finance researcher at the University of Kassel.

Klein says there is private capital in abundance in Germany waiting for productive and sustainable investments, but risk-averse German investors would need much more sustainable investment models with fixed interest rates. "We simply offer the wrong kind of financial products," Klein said. Yet others say that they do not invest their money at all and simply keep it in a savings account, he added. "But in that case, it’s the bank that does at it pleases with the money and the saver has no influence on it."

Green Finance Glossary

Asset management - The handling of financial investments by a professional agent

Best-in-class – Investment strategy that opts for funding leaders in given rankings in industries, technologies or categories

Carbon disclosure - Publication of climate-related activities by companies; spearheaded by NGO Carbon Disclosure Project and its disclosure leadership index

Corporate governance - The compliance of a company with laws, guidelines, voluntary agreements and other norms in its business conduct

Divestment – Withdrawal of capital from funds, equity or other capital assets from certain businesses or fields of operation, such as the coal industry

ESG –The Environmental, Social and company Governance dimension of business activities

ESG-Integration – The explicit inclusion of ESG-criteria in traditional risk analysis

Engagement – Long-term dialogue with invested companies to adapt investment decisions to ESG considerations

Exclusion criteria – Systematic elimination of certain investments or other categories, like companies or states, if they fail to abide by certain standard practices

Green Bonds – Bonds issued with the condition to finance environmentally friendly projects

GRI Standards - Globally used standard for sustainability reporting in finance launched by the Global Reporting Initiative Framework (GRI) since 1997

Impact investment – Investments made with the aim to make financial gains while also deliberately influencing ecologic and social developments

Integrated reporting - The inclusion of environmental and social impact information in company reporting to indicate financial and non-financial business aspects in parallel

Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) - Screening of funds to exclude companies which generate a given share of their revenue with activities conflicting with given environmental, social or ethical values

Sustainability-themed funds – Financing of business areas or other assets that are associated with sustainability and have a connection to ESG-criteria

Norms-based screening – Evaluation of investments according to given international standards, such as the UN Global Compact, OECD guidelines or others