'Net zero' Netflix is far from climate neutral

*** Please note: This article is part of the CLEW focus on company climate claims.

This dossier lists our existing publications and future content plans, and our upcoming events are here.

This blog explains why we decided to launch the project.***

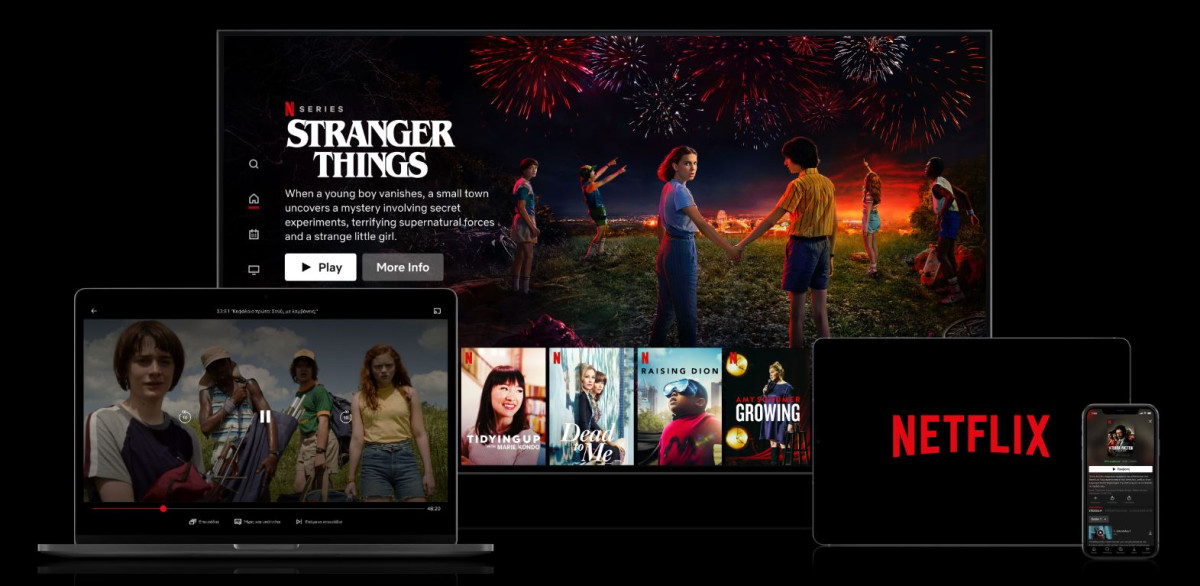

Digital video and music streaming services have quickly become a fixture of home entertainment across the globe, but the industry’s path to climate neutrality remains shrouded in uncertainties. Like many other large players in the film and TV industry – which is weakly regulated in environmental terms – the most popular streaming company, Netflix, has adopted voluntary targets for reducing its greenhouse gas emissions. The company said in 2021 it wants to “achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by the end of 2022, and every year thereafter.”

Netflix has not yet announced whether it has reached its target. But it is certain that the company will continue to cause emissions – its “net zero” target only means it will compensate its remaining CO2 output with carbon credits, a practice that has increasingly come under fire for being unreliable. In contrast to the net zero target, Netflix's emissions recently have risen strongly, and true climate neutrality remains a distant target: Neflix aims to reduce its direct emissions and those from using electricity (so-called scope 1 & 2 emissions) by 45 percent by 2030.

With its climate commitments, Netflix still goes further than most other players in the sector, according to industry experts. “Netflix is quite right in calling themselves a leader in the media field” in terms of the thoroughness of its reporting, believes Pietari Kaapa, who specialises in environmental media production policies and practices at the University of Warwick. Christiana Figueres, co-architect of the Paris Agreement and a member of Netflix’s net zero advisory group, said at the launch of the target: “Netflix’s Sustainability Strategy is music to our ears.”

It’s difficult to compare Netflix’s sustainability claims to those of its competitors, partly because a number of streaming rivals are folded within larger media empires, which don’t report the sustainability metrics of the streaming services separately from the rest of operations. But other studios have largely set targets of 2030 and beyond for reaching net zero in parts of their operations, and the Netflix target applies not only to its very own productions, but also to Netflix-branded licenses.

So while the BBC production ‘Killing Eve’ wouldn’t be included in Netflix’s net zero calculations, which can be watched on the site but is not ‘Netflix’ branded, the show ‘Call My Agent!’, which bears the Netflix logo on the streaming site, would. Like many of its peers, the company is very hesitant to talk about its environmental credentials, despite its much-lauded data transparency. No Netflix representative agreed to speak on the record for this article.

Cleaning up film production

Netflix says its entire carbon footprint rose almost 50 percent to 1.54 million tonnes of CO2 in 2021 – the year before it was meant to hit net zero – mainly as a result of an increase in post-pandemic film production. “We still have a lot of work to do within Netflix and across our industry before we reduce absolute emissions,” the company admitted.

Roughly half of the company’s climate footprint was generated by the physical production of Netflix-branded films and series, whether managed directly or through third-party production companies. The remainder came mainly from corporate operations like offices and purchased goods, and a further fraction from the use of cloud providers like Amazon Web Services, and the content delivery network used for streaming.

Netflix says in its latest sustainability report that it avoided over 14,000 tons of CO2 emissions in 2021 – less than 1 percent of the total. It uses three broad steps on its pathway to zero emissions: optimising energy consumption (such as right-sizing diesel generators); electrifying as much as possible (notably electric vehicles, although medium and heavy-duty electric vehicles remain a challenge to source); and then decarbonising whatever is left.

Controversial net zero strategies

Netflix’s plans for reaching net zero emissions involve several controversial strategies: carbon offsets, alternative fuels such as “renewable diesel”, and renewable energy certificates.

NGO Transport & Environment argues that renewable diesel uses essentially the same raw materials as biodiesel, resulting in similar pressures on feedstocks. Yet Netflix said the use of renewable diesel lowered emissions by 717 tons in 2021. Netflix is also relying on sustainable aviation fuel, which like renewable diesel is derived from biomass.

The company says it is using its scale and partnerships to incentivise technological innovations like hydrogen fuel cell units and mobile batteries, which remain limited in availability and capacity. But they could allow the full-scale replacement of diesel generators, which have been an environmental bugbear of film and TV production.

Netflix adopts alternative fuels in situations where it’s just about impossible to eliminate energy use, or switch to on-grid or renewable energy. The company also uses renewable energy certificates (RECs) to cover 100 percent of its electricity – a strategy that has also come under fire, because it generally doesn’t result in additional renewable capacity, but allows companies to take credit for renewable energy they don’t physically use themselves. Even with companies using science-based targets for emission reductions, as Netflix does, the use of RECs often doesn’t lead to more renewable energy or fewer emissions.

Along with RECs, Netflix depends on carbon credits to reach its net zero goal, and it is set to increase their use as it continues to grow. According to the Net Zero Tracker, Netflix’s carbon credit portfolio is strong: issued by credible standards, addressing permanence and leakage, and incorporating other aspects of environmental justice. But carbon credits remain open to criticism, as they allow a company to simply buy its way out of fully decarbonising itself. “I find that problematic as a rhetorical means of suggesting that they’re somehow reaching a sustainable goal,” Kaapa notes. “Ultimately if they really wanted to reduce damage, they’d have to cut back on content production.”

Indirect emissions remain an industry “mystery”

Netflix excludes the emissions from the streaming of its shows, and from the electricity used by TVs or computers while watching them, from its net zero calculations. “We don’t include emissions from internet transmission or electronic devices our members use to watch Netflix. Internet service providers and device manufacturers have operational control over the design and manufacturing of their equipment, so ideally account for those emissions themselves,” the company says.

But it remains ambiguous whether these so-called Scope 3 emissions (indirect value chain emissions) should be included in the climate plans of streaming companies. Netflix itself acknowledges that guidance around corporate near-term net zero targets is unsettled.

While the film and TV industry has taken strides to address their direct (Scopes 1 and 2) emissions, “Scope 3 emissions is still in many ways a mystery to the industry,” according to Kaapa.

GHG Protocol, which is responsible for the most commonly used greenhouse gas accounting standards, doesn’t offer specific guidance on web-based streaming. But David Rich, the organisation’s deputy director, says that “it is very similar to web-based software, which is classified as a direct use phase emission”. In other words, web-based software should be included within required Scope 3 emissions, rather than the optional ‘indirect use phase’ emissions.

In practice, digital content providers have taken different approaches to reporting on customers’ emissions. For example, music streaming service Spotify does account for its customers’ streaming, which made up 42 percent of the company’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2020. Given that video streaming is much more energy-intensive than audio, the emissions from more than 220 million customers while watching Netflix content are likely substantial. But overall, streaming video is by far not as energy-intensive as some wildly exaggerated media reports have suggested, mainly due to rapid efficiency improvements in data centres, networks and devices. “Contrary to a slew of recent misleading media coverage, the climate impact of streaming video remain relatively modest, particularly compared to other activities and sectors,” concluded a CarbonBrief analysis.

Hunter Vaughan, an environmental media researcher at the University of Cambridge, believes that responsibility for this energy consumption should fall to content providers like Netflix and to governments, but it remains unclear how that could work in practice. “I’m not sure that we can set a timer to force Netflix to shut off someone’s binge,” Vaughan said.

At the same time, companies like Netflix have enormous power to nudge customers in less energy-intensive directions, for instance by offering low-definition streaming options, and changing automatic ‘Play Next’ settings, says Carolina Koronen, programme manager at the Environmental Coalition on Standards (ECOS), which is calling on the EU to set minimum requirements on energy consumption for companies like Netflix.

However, Netflix-funded research concluded that “changes in video quality [have] only a very small impact on carbon emissions.” The streaming company has been working with external researchers to measure the carbon emissions associated with streaming, and with internet service providers and device manufacturers on accounting for customers’ emissions. According to Netflix, this is part of its sphere of influence but not within its own remit, and thus outside of official net zero calculations. Therefore, Netflix is trying to shape conversations around internet-related emissions without taking full responsibility for them.

If a regulator does impose energy requirements, “I think the system boundary will end just before the consumer side,” Koronen acknowledges. But digital industries have a great deal of potential to be more ambitious, she adds.

Without stronger external guidance on where companies’ responsibility for emissions ends, Netflix and others will be able to continue picking and choosing, to some extent, the content of their net zero claims. A lot remains to be done before Netflix can be called a truly climate neutral company – regardless of its 2022 net zero target.