The heat is on to make German buildings 'nearly' climate-neutral

Energy guzzling buildings

Less than a quarter of German homeowners thought of "heating" when asked which words they associated with the energy transition in a 2019 survey commissioned by heating industry association ZVSHK. Convincing them to replace their heating systems with a low-emissions alternative is, however, a crucial step on Germany' path to climate neutrality by 2050. By that year, the government has said it wants a "nearly climate neutral building stock".

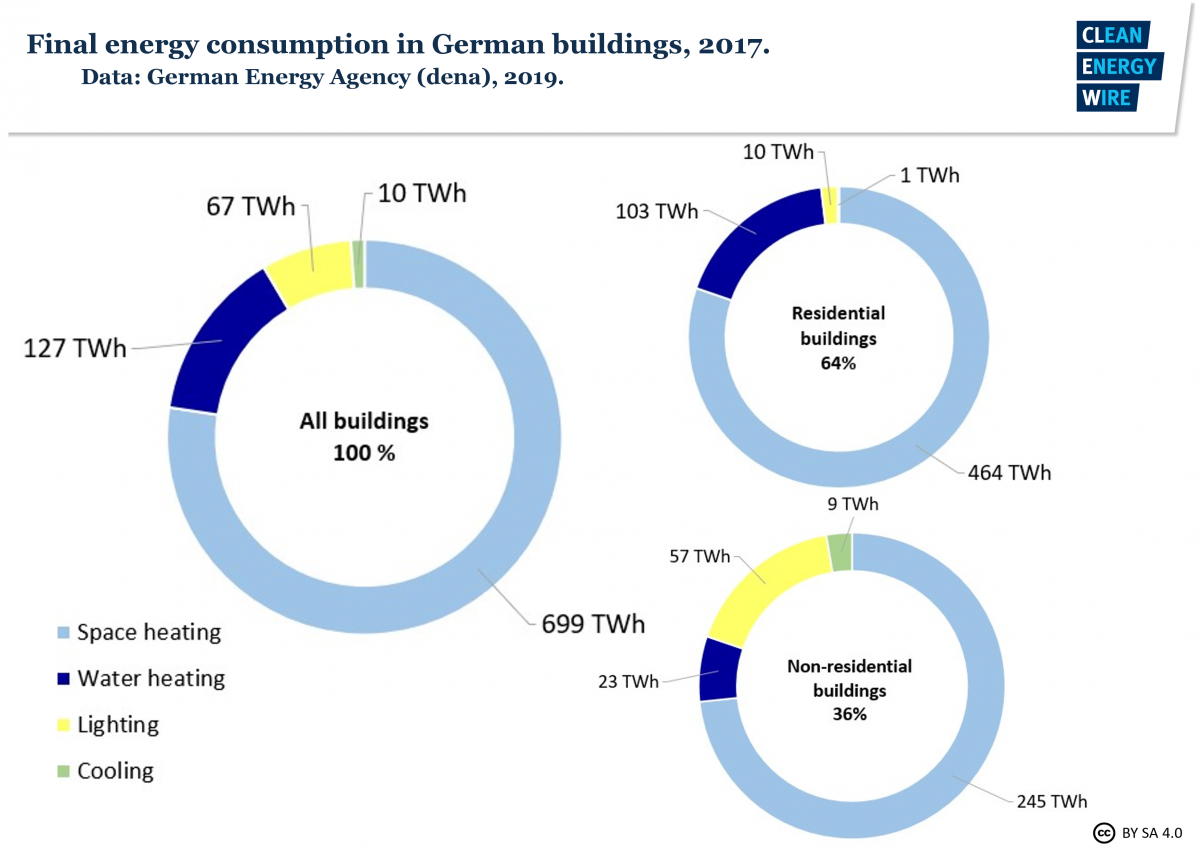

Almost a third of Germany's total final energy consumption in 2018 went into space and water heating in buildings. The building sector's greenhouse gas emissions, which arise almost solely from heating, add up to 15 percent of total emissions – and almost 30 percent including indirect emissions. In effect, "there will be no Energiewende without the Wärmewende", argues the Federation of German Heating Industry (BDH) – a statement echoed by many others.

Including process heat, heating accounts for more than half of Germany's final energy consumption. Process heat refers to the various types of heat transfer techniques used in industrial production, where for example steel, cement and chemicals are manufactured at high temperatures. Reducing emissions from the heating of Germany's close to 22 million buildings is, however, proving a challenge in itself.

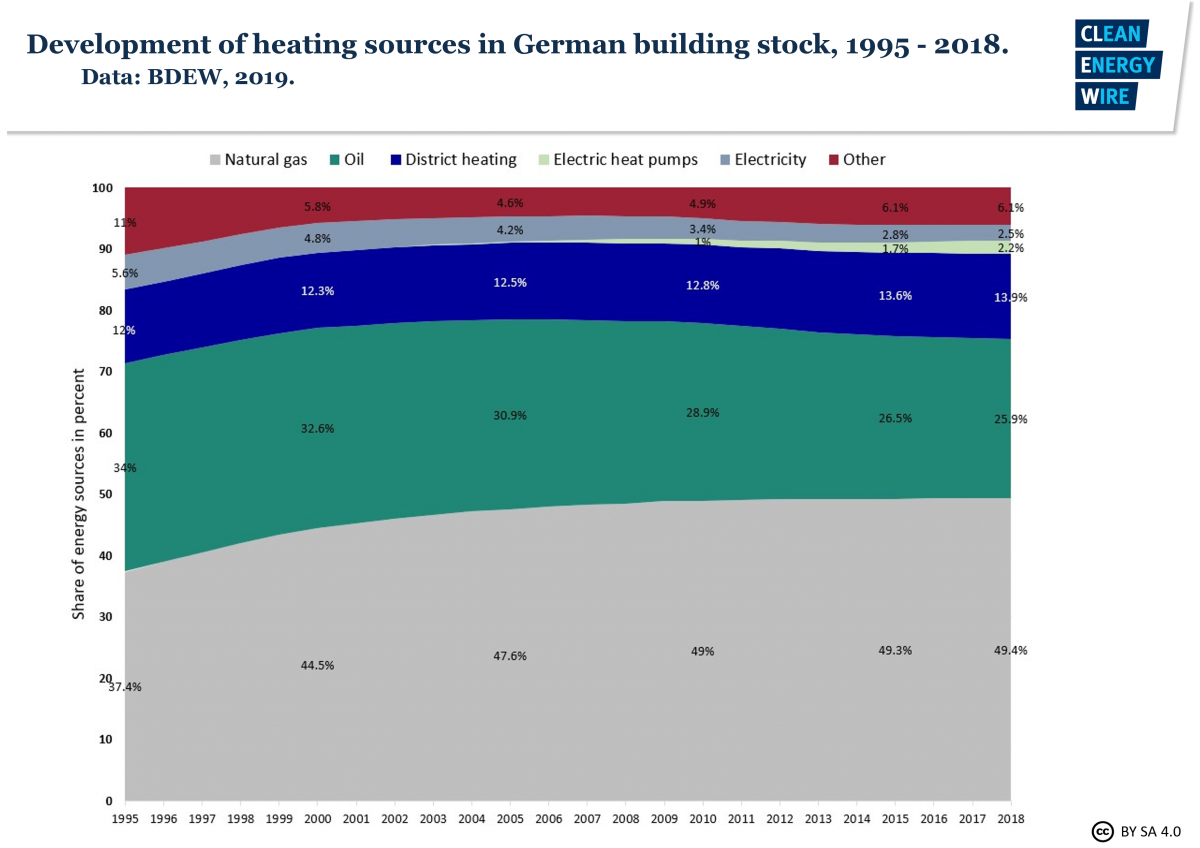

The task is twofold: increasing the amount of heat coming from renewable sources while reducing energy consumption. Currently, more than 90 percent of Germany's heating systems are fuelled with oil and natural gas, the Federation of German Heating Industry (BDH) estimates. More than half of all heating systems are considered inefficient by today's standards. This leaves an enormous potential to cut emissions. In fact, the BDH estimates that just by replacing the almost 12 million outdated systems, Germany could save two thirds of the 70-72 million tonnes of CO2 it targets to curb in the buildings sector by 2030. So, what's the problem?

Extremely heterogenous – and expensive

Compared to the power sector, the heating sector involves a tangle of technologies, stakeholders, cost and market structures. This "extreme heterogeneity" makes the sector hard to move, professor Kai Hufendiek, energy researcher at the University of Stuttgart told Clean Energy Wire. Instead of a few central energy companies, a huge number of decision-makers like tenants, homeowners and landlords must make decisions and bear the high investment costs for new heating systems and energy efficient building renovations directly themselves. At the same time, information about energy efficiency is lacking, as are specialists with sufficient training in installing new, climate-friendlier technologies.

But energy efficient buildings are vital to the transition in heating as they open the door to a range of climate friendly technologies. The economy ministry estimates that about half of Germany's 19 million residential buildings are going to need renovation by the mid-2020s. A yearly modernisation rate of two percent is targeted, but the current rate lies at around half of this.

Political hot potato

As rising rents, scarce living space and rising construction costs already burden parts of the population, politicians want to ensure that climate-friendly policies in the sector do not create social backlash. Experts claim that years of political procrastination have led the heating transition to fall short of targets. Most of the technologies needed to succeed with the Wärmewende are there, says Kajsa Borgnäs, director of the IGBCE's foundation for labour and environment. "What we are really dealing with here, I think, is a policy failure."

Indeed, the German government has stumbled in several attempts to put efficient heating on the agenda. In 2019, the interior ministry led by Horst Seehofer cancelled the buildings commission intended to identify ways to reduce the sector's carbon footprint, while in 2017, the German government coalition failed in a first attempt to agree on a building energy law, which would have set new standards for efficiency in buildings. The NGO Environmental Action Germany has compiled a "chronology of failures" in the sector, starting from 2008.

28 million tonnes off target

After years of standstill, the energy used in Germany’s buildings has not fallen nearly as much as targeted. Instead of dropping by 20 percent between 2008 and 2020, final energy consumption had only gone down by 6.9 percent in 2017. Although greenhouse gas emissions in the building sector have fallen by about 42 percent since 1990, progress has largely stagnated since 2011 and studies show the need to significantly ramp up action.

"Without additional efforts, we estimate that greenhouse gas emissions from buildings in 2030 will be up to 28 million tonnes above the target of 70 to 72 million tonnes," Andreas Kuhlmann, head of the German Energy Agency (dena) has warned. This would mean Germany having to pay significant fines under the EU’s “burden sharing” scheme. How the measures in the government's new climate action package will affect this picture, however, remains unclear.

Fossil-fired status quo

At present, almost 65 percent of Germany's 20.7 million heating systems are fuelled by gas and about a third are oil-fired. Only about four and five percent are respectively biomass boilers and heat pumps. Renewables covered just above 14 percent of all heating in 2018, overwhelmingly supplied by biomass. This level is right on target, but has also stagnated for almost a decade.

Although some development is seen in the area of new buildings, existing German households' preferred energy source when switching has over the last ten years – with more than 80 percent – remained natural gas. Keeping in mind that heating systems often have a working life of 30 years, this is "an unfavourable development, from my point of view," says Hufendiek, "because all the heaters we install today will still be in operation or will only by replaced by 2050. By that time, we aim have to have eradicated all emissions from space heating already." A dilemma known as the lock-in effect.

To avoid this situation, the UK, on its part, has announced a ban on gas boilers in new homes from 2025 while the Netherlands, a long-time major gas producer, aims for all of the country's residential buildings to be off gas by 2050. In Germany, however, government support for gas heaters is planned to continue for systems that can be made "renewables ready" within two years after installation.

The German heating industry, with well-known names like Bosch, Viessmann and Vaillant, is a market leader in classic oil and gas boilers, Volker Breisig, partner in business consultancy PwC’s energy practice told Clean Energy Wire. “You could compare it to the German car industry, which banked on what was successful for a very long time – the classic engine.” But by now, it has – like BMW, Daimler and Volkswagen – embraced the need for a swift transition to more climate-friendly solutions, adds Breisig. The sector still faces challenges in moving its focus to other technologies, more complex energy management systems and the many possibilities in sector coupling, however, he says.

Part of the slow development in the sector has been a lack of political direction, says Breisig. Although changes are happening in new buildings, “we still don’t have a clear roadmap for the existing building stock." This has led to an overarching trend of “wait-and-see”, when it comes to both renovation and replacement of systems, he adds. "Politicians have long failed to realise the importance of setting the right framework conditions." If the electricity needed to operate a heat pump remains too expensive in comparison to the use of gas or oil, the industry will continue to have a hard time selling the more climate-friendly alternative.

Scale-up of all climate-friendly heating systems needed

Meanwhile, the clock is ticking. "Past neglect" means that a nationwide upscaling of all available technology options is now needed for Germany to reach its buildings sector targets, shows a study by think tank Agora Energiewende*, research institutes ifeu, Fraunhofer IEE and consultancy Consentec.

Their projections show that reducing the energy use in buildings is the most cost-effective condition to reaching targets – and the key to being able to employ a wide range of climate-friendly technologies. A scale-up of electric heat pumps, decentralised renewables such as geothermal and solar energy and the expansion of district heating networks, coupled with the use of synthetic gas, are possible paths to a nearly climate-neutral building stock, they estimate.

Electric heat pumps would form an energy-efficient alternative to gas boilers in many buildings – and an increasingly climate-friendly alternative if Germany's share of renewables in power consumption increases as targeted. Agora Energiewende, in a study from 2017, recommended the installation of five to six million heat pumps by 2030. Converting the bulk of German heating systems to electricity would, however, necessitate further expansion of electricity grids and increase power loads, says a study by dena and the German alliance for energy efficiency in buildings geea. Nonetheless, coupling the power and heating sector is increasingly seen as a way forward for Germany.

Power-to-x is another buzzword in Wärmewende debates. Dena and geea play out a scenario where electric heat pumps are supplemented by power-to-gas and power-to-liquid. But experts warn that these technologies are expensive and inefficient as a solution for heating buildings, as a lot of energy is lost in the transformation process. Relying mainly on power-to-gas, most of which Germany would need to import, would be an expensive choice in the heating sector where more efficient alternatives exist, says Agora Energiewende's study. Germany's new National Hydrogen Strategy, however, states that the government is also, in the longer term, looking at hydrogen's potential in parts of the heating market. "Once the efficiency and electrification potentials in process heat production or in the building sector have been exhausted, there will still be a demand for gaseous energy sources," it adds.

Instead, the expansion of district heating networks fed by geothermal, solar energy and excess industrial heat is seen as a possible path to decarbonising buildings, especially in densely populated areas.

Climate package turns up the heat

With its climate action programme from September 2019, the German government has, however, started to point in a direction for the future. A "swap-premium" for old oil-fired heating systems and a ban from 2026 in buildings where more climate friendly alternatives are available have been introduced. Long-awaited tax incentives for a range of energy-efficient renovations for homeowners came into force in January 2020. Germany's national carbon pricing system which covers the buildings and transport sector is also meant to encourage the switch from fossil fuels to more climate friendly energy sources for heating.

The CO2 price, bumped up from 10 to a starting price of 25 euros per tonne from 2021, is a step in the right direction, but it is still too low to eliminate the price imbalance between using fossil fuels and renewable electricity for heating, says PwC's Breisig. "At least a course has been set for the heating sector to slowly move forward. It remains to be seen whether the measures are sufficient or will be accepted by citizens," he adds.

Christian Stolte, division head of energy efficient buildings at dena, says the climate package contains many good approaches and measures to end ten years' standstill in the buildings sector. He is hopeful that the climate package and innovations such as serial building refurbishment and smart technologies can even make the energy transition in the building sector a model for success. If Germany wants to reach its 2030 and 2050 climate targets it is, however, "extremely important that the transition takes off as quickly as possible," says Stolte.

A 2018 study commissioned by the public utility MVV projected that even with optimistic cost degression, low-CO2 heating alternatives will remain significantly more expensive than conventional fossil-fuel technologies in the year 2040. The same study estimates that Germany will need to fill a yearly financing gap of nine billion euros in 2030 and 23 billion euros in 2040 in order to reduce emissions from buildings by 80 percent by 2050 compared to 1990.

Support for this daunting task could, however, be arriving by way of the EU, whose Green Deal proposes a "renovation wave" of public and private buildings, reportedly one of the flagships of the new European Commission.

*Like the Clean Energy Wire, Agora Energiewende is funded by Stiftung Mercator and the European Climate Foundation.