First 100 days - German government in disarray neglects energy policy

Germany’s energy and climate policies have come under the wheels of an internal crisis between the coalition parties over immigration. After its first 100 days in office, the fourth German government under Angela Merkel has descended into a conflict that is unprecedented for the Chancellor who has governed Germany since 2005. The row within the coalition’s conservative camp, consisting of Merkel’s CDU and its Bavarian sister party CSU, has brought the three-party coalition - that also includes the Social Democrats (SPD) - to the brink of collapse, and is seen as part of the reason why little progress has been made in several key policy areas since the government started its work in early March.

In an unusual alliance, traditional energy companies, the renewables industry, and environmental organisations have lambasted the government for its inaction, arguing that it hurts both Germany’s climate ambitions and the economic prospects of companies relying on secure planning conditions.

Germany has been slowing down climate action “domestically and at the European level,” said Renewable Energy Federation President Simone Peter. She said the uncertainty was a liability for companies, as they had no way to plan their production capacities for the renewables expansion the government has envisaged, and added that no progress whatsoever has been made on reducing emissions in the transport and heating sectors since the government took its oath of office. Stefan Kapferer, head of the utility association BDEW, said that “we are at a standstill, and we cannot afford this,” adding that today Germany’s energy industry is making greater efforts to advance the energy transition than the government itself.

Things could change after parliament’s summer break, when Germany’s long anticipated coal exit commission is scheduled come up with results, and once several important energy laws have been approved by the cabinet. However, the government’s first 100 days have left many observers dissatisfied. The coal commission got off to a bumpy start, the roadmap for renewables expansion is still unclear and looming diesel driving bans in many major cities are set to further spur public outrage with a government that nearly 60 percent of Germans are unhappy with, as recent polls suggest. Meanwhile, several policy areas related to the Energiewende - the country’s dual shift from fossil and nuclear energy sources towards an energy system based on renewables - would require rigorous and swift action.

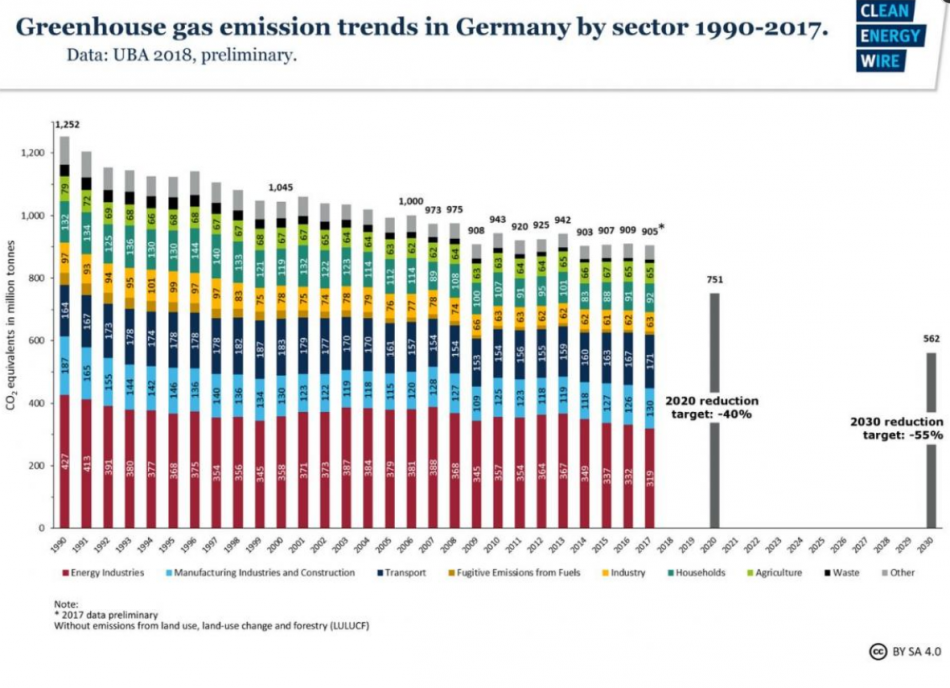

On top of that, the government had to officially confirm that Germany’s 2020 emissions reduction target has slipped out of reach - an admission that has significantly damaged the government’s image as a climate action champion in the eyes of the environmental groups.

“The grand coalition has to finally take climate action seriously and walk the talk,” Green Party leader Annalena Baerbock told the Clean Energy Wire. “The climate crisis won’t be stopped by declarations of intent and by holding workshops,” she said. Lukas Köhler, climate politician of the pro-business opposition Free Democratic Party (FDP), said the numerous, albeit mostly minor, frictions between the ministries involved in climate action cause one big problem for Germany’s policymaking, namely a lack of coordination. “If this doesn’t change, climate policy is not set to improve,” Köhler told the Clean Energy Wire. “There’s no clear indication which route we’ll take in the future. It rather seems that they want to keep alive the status quo,” he added.

"I can’t work with this woman anymore!"

Chancellor Merkel has acknowledged Germany’s waning reputation as a global leader on climate action, saying that its climate policy must become “more binding,” and must counter the international trend towards unilateralism that imperils the fight against global warming as a whole. While Merkel’s remarks made at the Petersberg Climate Dialogue in Berlin might be considered an adequate self-assessment and a laudable commitment to international cooperation, the government’s track record after its first 100 days in office is overshadowed by the conservatives’ infighting over immigration, which has the potential to shake the nearly 70-years-old alliance between the CDU and the CSU at its core.

Driven by the fear of losing important votes to the right-wing nationalist Alternative for Germany (AfD) party in the Bavarian state elections in September, former Bavarian state premier and CSU leader Horst Seehofer, who since March has headed the interior ministry (BMI), has set out to vehemently oppose the liberal asylum policies associated with Merkel ever since the refugee crisis peaked in 2015. The rift has reportedly led Seehofer to exclaim that “I can’t work with this woman anymore!,” and Merkel to publicly remind her restive minister that it is the chancellor who has the final say in German policymaking.

The brawl between the two conservative party leaders, which some observers believe could spell the end of the conservative alliance and lead to the break-up of the fledgling government coalition, also indirectly impedes on the work of energy and economy minister Peter Altmaier, who is a CDU member. On the one hand, the AfD’s influence on the political climate can also be felt in energy policy, according to an assessment that appeared in the Tagesspiegel Background. Fears within the economy and energy ministry (BMWi) that the prospect of further burdens caused by progressive energy transition policies could make voters susceptible to calls from the far right that the whole Energiewende is expensive and inefficient bogus have prompted Altmaier to put important and even already agreed measures on halt for the time being.

On the other hand, the former head of the Chancellery is directly implicated in the quarrel, as he oversaw Germany’s refugee policy in his capacity as Merkel’s special envoy during the previous legislative period, which according to the newspaper Die Welt prevents Altmaier from fulfilling his responsibilities for Energiewende policymaking.

Most strikingly, Altmaier had to postpone the introduction of a so-called “100-day-law,” which was scheduled to set the rules for combined heat-and-power installations and for two special renewables auctions within the government’s first 100 days in office. It is meant to help Germany reach its increased goal of 65 percent share of renewables in power consumption by 2030. Just like another law Altmaier had promised to speed up the expansion of Germany’s power grid, the changes will now only come in September, after parliament’s summer break.

Hopes pinned on 2019 Climate Protection Act

Scepticism with the government’s 2030 aims is rife among renewable energy companies. According to a survey conducted by industry organisation Renewable Energy Hamburg, over two-thirds of the companies considered it unlikely or very unlikely that the government’s renewables expansion goal will be met – and 85 percent answered that a carbon floor price would be the best way to boost renewables at the expense of fossil power sources - a policy also proposed by French President Emmanuel Macron. But while Altmaier insists that both the 2030 emissions reduction and the renewable expansion targets will be met, he has consistently rebuked the idea of changing Germany’s system of energy-related fees and levies.

The Social Democratic Party’s (SPD) climate politician, Matthias Miersch, directly attacked the minister, saying that his impression was that “Altmaier has fundamental problems ensuring the basic functions of his ministry.” In an interview with the Göttinger Tagblatt, Miersch criticised the economy and energy ministry for still lacking a state secretary who would assist the minister in policy coordination and implementation, and warned Altmaier that he should forget about the Social Democrats’ support “if he keeps putting on the brakes” in climate policy.

The energy minister was given more forbearance by Herman Albers, head of the wind power association BWE, who said that the SPD, and the best part of Altmaier’s CDU, were trying to deliver on their election promises on issues related to energy and climate. “But just like in migration policy, the conservatives’ right wing is the biggest blocker here,” Albers said. Energy and migration are the most contentious issues the government has to deal with, he explained. “But the parties would be wise to better cooperate on energy and climate policies, in spite of all their differences. This could strengthen the government as a whole.”

The BWE and other renewable energy organisations now pin their hopes on a Climate Protection Act promised by environment minister Svenja Schulze (SPD), which is slated for introduction in 2019. “The Climate Protection Act is decisive,” said Carsten Körnig of the national solar power association BSW Solar. “We used to be content with the coalition treaty,” he conceded. “But if we don’t start implementation soon, we’ll end up in a situation similar to the current one by the end of the 2020s. What we don’t reduce soon, we’ll have to reduce in the second half of the next decade,” Körnig said.

"Big problem child" transport

Schulze’s environment ministry (BMU) has also come up with a proposal to tighten emissions limits and halve the CO2 emissions of cars to match the EU’s standards, arguing that the current limits would make it impossible for Germany to reach its climate protection targets. Chancellor Merkel has called the transport sector “our big problem child,” as disagreement within the government also reigns supreme in that field. Transport minister Andreas Scheuer from the CSU said that the tighter limits are “arbitrary,” and risk to “obliterate Europe’s most important industry.”

But Scheuer has already seen his policy position overruled in the past, when, back in February, a court gave the green light to inner city driving bans for diesel cars to curb nitrogen oxide levels and to avoid being sued by the European Commission over excessive air pollution. Scheuer has repeatedly shrugged off warnings against these bans, saying that his motto was “no panic, no bans,” and arguing that mechanical retrofits for manipulated diesel cars were not necessary - although environment minister Schulze said they are indeed necessary to avoid EU fines. The first bans were then introduced in Hamburg in early June – and the EU still sued Germany over too high pollution levels.

But in a recent interview with Die Welt, Scheuer revealed what has topped his priority list lately, at the same time giving a succinct metaphor for the CSU’s policy position. “We have more money in our coffers than ever before,” he said, referring to the government’s financial leeway. “But that’s practically meaningless. We could give people golden pavements, but all they want is concrete answers to, and measures on, immigration."