Europe struggles to heat homes without cooking the planet

***Please note: We have also published the factsheet What are the best technologies to heat homes cleanly? to complement this article.***

When German economy minister Robert Habeck tried to ban the installation of new gas boilers from 2024 — a bid to cut carbon pollution and boost energy security — the country's most powerful newspaper hit back hard. For weeks in May, headline after headline slammed "Habeck's heat hammer" on the home screen and frontpage of tabloid Bild. Europe's best-selling newspaper warned readers the law would smash their savings, destroy their retirement provisions and force intrusive renovations. Cracks quickly widened in the ruling coalition between the Greens, who want to heat homes mostly with electricity from renewable sources, and the Free Democrat Party calling for "technological openness" that includes burning a range of gasses. In cellars across the country, boilers that for decades had sat gathering dust were suddenly a symbol of the German energy transition and the culture war surrounding it.

Germany's fight to heat homes without cooking the planet is playing out in countries across the continent. The technologies to meet the 1.5 degrees Celsius target in the building sector are there, but the social acceptance of the hassle and cost is not, said Adeline Rochet, an expert in decarbonising buildings at the climate think tank E3G. "In simple English, it's going to be very hard but not impossible."

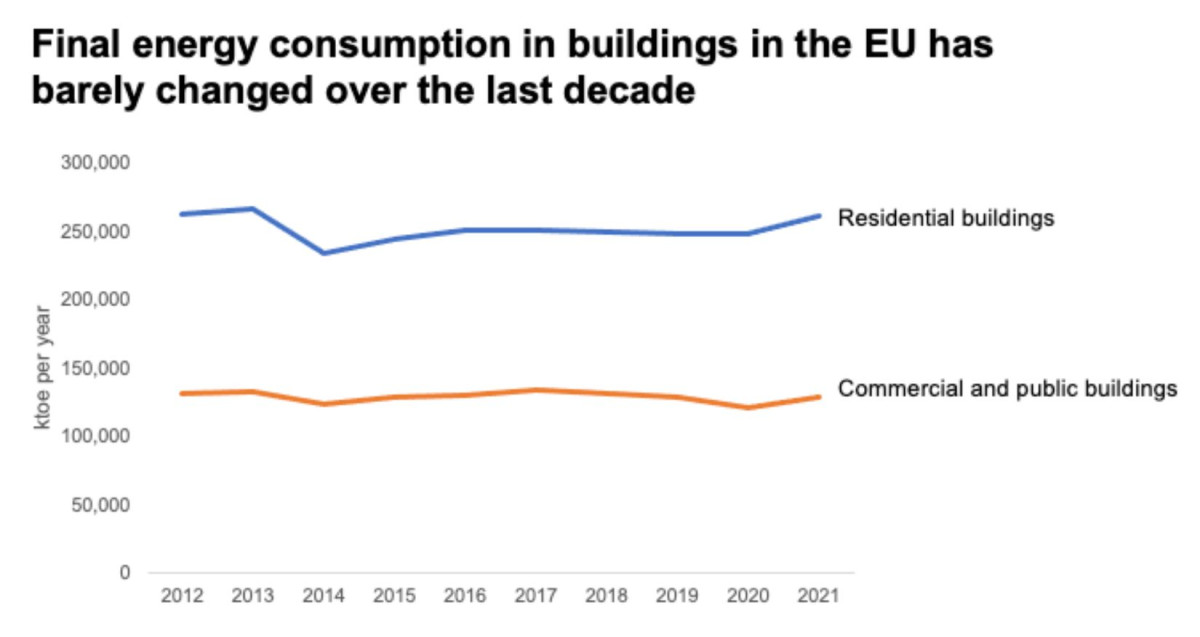

Half of the total energy consumed in the EU in 2020 was used for heating and cooling, typically by burning fossil fuels, with the bulk of the demand coming from buildings and one-third from industry. But despite green ambitions, progress in bringing that down has been "sluggish", according to the European Environment Agency. In some countries that have swapped to clean technologies, like Sweden and Greece, greenhouse gas pollution from energy in buildings has more than halved in the last decade-and-a-half. In others, like Romania and Lithuania, it has barely budged. EU-wide building emissions dropped by a third between 2005 and 2020 but are not falling fast enough to meet the bloc's unofficial target of a 60% cut from 1990 levels by the end of the decade. Just 8 countries — Austria, Czechia, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Luxembourg, Slovenia and Sweden — are expected to cut emissions by more than 55% with policies suggested by the European Commission but not yet written into national laws.

So far, the progress the EU has made in getting building emissions down mostly boils down to cleaner electricity grids, better-designed houses and milder winters — a result of climate change — though these gains have been partly offset by an increase in the average floor area per person. Unlike in other sectors, where clean technologies like vegan meats and electric cars have captured public attention, the tools to clean up building heat are neither glamorous nor well-publicised.

There are two core approaches: cutting demand for energy and supplying it from cleaner sources.

Pumping heat from outside into homes

The second of these is proving the most controversial. The most powerful technological fix, according to experts, is to replace fossil fuel boilers with heat pumps. These devices act like reverse fridges, using a coolant to suck heat from the surroundings and push it around a home. They can also double up as air conditioners. If the electricity that powers the pump comes from renewable sources, the warmth generated is carbon-free. If powered by a dirty electricity grid, they are less climate-friendly — but still have lower emissions than a gas boiler. Heat pumps are particularly efficient because they don't generate heat themselves, they just move it around.

For world leaders to honor their climate promises, one-quarter of global heating needs will be met by heat pumps in 2030 and half by 2050, according to modeling from the International Energy Agency, a Paris-based organisation led by the energy ministers of mostly rich countries. A roadmap to cleaning up the German economy from Agora Energiewende, a climate think tank, shows heat pumps powering most residential buildings in Germany as early as 2035.

Places that have adopted heat pumps fastest — cold Nordic countries like Norway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark — tend to be rich, with lots of cheap and clean electricity, as well as a carbon tax on heating fuels. Together, these make heat pumps even cheaper to operate than fossil fuel boilers. Still, experts are wary of comparing the cost of a heat pump and a gas boiler because it depends on so many factors: the specifics of each building; the level of government subsidies and taxes; and the volatile prices of electricity and fuel. But they agree that a heat pump usually costs more to install but less to run.

Still, the heat pump's dual role has been overlooked in debates around its price tag, said Kevin Kircher, a mechanical engineer at Purdue University in the US who specialises in buildings. Because the technology is so similar to an air-conditioner, heat pumps can be used to heat homes in winter and cool them in the summer — though not all heat pumps are designed to do so or easy to retrofit once installed.

Temperatures in Europe have increased more than twice the global average due to climate change in the last 30 years, according to the World Meteorological Organisation, making extreme heat waves hotter and more likely. But few of its homes have air-conditioning and demand is set to soar. In the US, where nearly 90% of homes are air-conditioned, the cost difference between a gas boiler and a heat pump is "miniscule" in new buildings because the heat pump can serve both heating and cooling needs, said Kircher. "In existing buildings, the calculation is a little bit different because a homeowner may not be replacing both a furnace and an air conditioner at the same time."

Sales of the long overlooked technology have started to grow exponentially. Last year, 3 million heat pumps were sold in Europe — a growth rate of 39%, beating the previous year's 34% growth rate. "For us, really, 2022 was really the turning point for the heat pump industry," said Jozefien Vanbecelaere, head of EU affairs at the lobby group European Heat Pump Association (EHPA). The Covid-19 pandemic got people thinking about air quality, Russia's invasion of Ukraine pushed people to stop using its fuel, and the EU responded to the Inflation Reduction Act in the US by setting "very ambitious" targets, she said.

The boldest of those targets comes from the European Commission, which wants by 2030 to add 30 million more water-based heat pumps, which work by using external heat to warm water in pipes. Adding in air-based systems — which use heated air to keep a home warm — the EHPA expects the existing heat pump stock will need to quadruple to 60 million by 2030. But bringing down the relative cost of heat pumps in existing buildings is still one of the biggest obstacles to rolling them out, said Vanbecelaere. This, she added, includes "shifting taxes and levies from the electricity bill to the fossil fuel bill [and] introducing a carbon price." In the EU, electricity has for several years been about three times more expensive than gas.

On top of that, some analysts fear a looming shortage of skilled workers who can install heat pumps and a lack of a serious plan to train them. There are also cases where residential heat pumps work poorly — for instance, temperatures below -30 degrees Celsius — or are ill-suited, such as in some apartment buildings with limited space, multiple owners and tight planning restrictions. Experts point to alternatives like district heating, where heat is generated centrally — perhaps from a giant heat pump or by burning waste — as well as solar panels that can heat water. In the case of district heating, which is already widely used in many European countries, the fuel source would need to swap from fossil fuels to cleaner sources of energy, or be fitted with technology to capture carbon.

Burning cleaner gasses

The biggest tension point, though, is whether other gasses should also be seen as part of the solution.

"I think it's fair to say it's obvious that electric heat pumps and district heating will play a critical role — depending on the member state and depending on the region," said Andreas Guth, a policy director at industry lobby group Eurogas. "The issue really is how far we can also use renewable and low-carbon gasses to ultimately decarbonise the existing use of molecules in heating. And that's something that we find is often being overlooked."

These gasses include hydrogen, a gas that burns cleanly but is in short supply, and biomethane, a purified form of the gas made when bacteria break down organic waste without oxygen. Some environmental groups fear the promise of these gasses will keep the infrastructure for natural gas alive.

In Germany, the government nearly tore itself apart over a draft heating law that called for all new heating systems to run on at least 65% renewable energy — an effective ban on new gas boilers starting in 2024. After pushback from the FDP, the coalition added a series of exceptions. They agreed to stop installing fossil boilers in existing buildings once the local authority has submitted a heat plan, which should be finished by 2028, and leaves some room for conventional boilers to be installed if they can be converted to run on hydrogen.

Heating homes with hydrogen would avoid the need for dismantling existing gas infrastructure and ripping boilers out of homes. But today, nearly all hydrogen is made from natural gas, also known as fossil gas. Experts are skeptical that enough green hydrogen can be made to satisfy both the needs of the building sector — which has other solutions — as well as sectors that definitely need hydrogen to decarbonise, like steel and shipping.

Where it could make sense, said Kircher, is as a back-up on the coldest days when high electricity demand strains the grid. "It probably doesn't involve running huge pipelines of hydrogen around and having hydrogen be the main heating fuel. It may be only 5% of the total energy that's used for heating comes from hydrogen — and we all just have little canisters of hydrogen we use a week or two a year."

The gas industry is pushing EU policymakers to refrain from specifying which technologies should be used to decarbonise heating and instead base the decision on local conditions — particularly by blending in hydrogen and biomethane. "We're not claiming that using a lot of natural gas and a tiny portion of hydrogen would be a way to decarbonise the building sector," said Guth. "But it's part of the process."

Still, some analysts fear leaving that door open to new gas boilers is a gamble not worth taking. "The risk is that we just do business as usual under the disguise of hydrogen-readiness and then we end up in 2040 and it's like, 'Oh gosh, there isn't any hydrogen, or it's too expensive,'" said Jan Rosenow, director of the Regulatory Assistance Project, a clean energy think tank. "It's used as a distraction, it's used to delay the process, and I'm afraid it has been fairly successful in some places already as a tactic."

The German gas industry has celebrated the coalition government's compromises on hydrogen and biogas in its new heating law.

Cutting demand for energy

Experts also caution against focusing on energy supply without tackling demand. About one-third of the buildings in Europe were built more than half a century ago, according to a report from the European Commission in 2021, and three-quarters are energy inefficient — meaning that a large share simply goes to waste. By insulating walls and lofts with fabric — and fitting drafty windows and doors to keep out chill winds — homes hold heat longer. Heating bills fall, after an upfront investment cost, and residents live healthier and more comfortable lives.

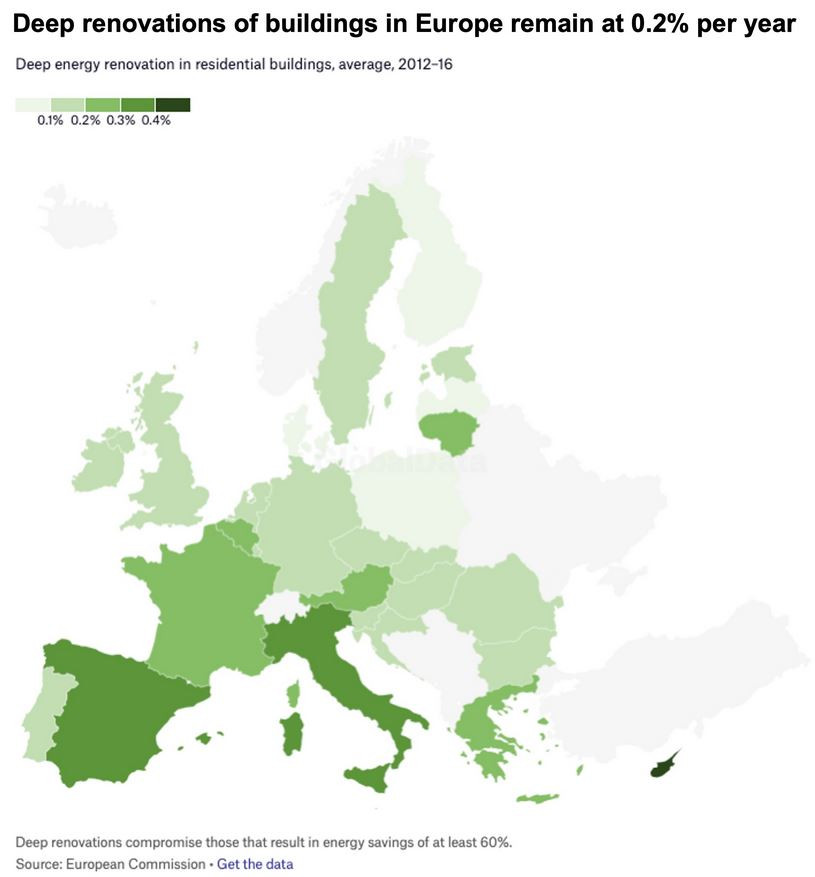

But only about 1% of the European building stock is renovated each year. Deep renovations, which yield energy savings of more than 60%, take place in just 0.2% of EU buildings annually. According to a report from the Buildings Performance Institute Europe, a think tank pushing for cleaner buildings, the EU must increase this 15-fold by 2030 to meet its climate targets.

Residents also have some power over their heating emissions. Shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, the IEA released a 10-point plan to cut Europe's reliance on Russian gas. It found Europe could cut gas demand 7% by turning thermostats down 1 degree Celsius. The average European home is heated to 22 degrees Celsius but the level needed for good health — for those without underlying health conditions or the elderly — is a few degrees cooler. Installing smart meters that regulate temperatures, or making behavioral shifts like wearing jumpers and slippers indoors, can bring emissions down further.

But as with heat pumps, the problem is making changes in millions of individual households, said Rochet from E3G. "This is not one big thing that you can swap. It's not a plant that you can just replace. It's a multiplicity of small appliances that at the end add up to represent a huge chunk of energy and a huge chunk of emissions."