Corona crisis shakes up shift to sustainable urban mobility

Will the corona crisis slow the shift to low-emission urban transport systems? Or might it be an opportunity to speed up the transition?

Mobility experts offer arguments for both scenarios, but most fear that the pandemic will cause at least a temporary setback to cleaner mobility - unless authorities make a decisive push for green transport.

"It is clear that the corona pandemic is fundamentally changing our mobility behaviour," said Barbara Lenz, who heads the Institute of Transport Research at the German Aerospace Centre (DLR). "The big question is: Are we only dealing with a temporary shift, or is it here to stay?"

Mobility researcher Weert Canzler from the Berlin Social Science Centre (WZB) also said that specific forecasts remain elusive because the impact of the crisis is so complex. Long-term effects will be shaped by pending policy decisions, and by how the pandemic will unfold in the months to come.

"So far, the crisis presents us with very ambivalent and uncertain mobility results. Following the easing of lockdown restrictions, the use of cars and bicycles has gone up, and public transport is also bouncing back slowly," Canzler told the Clean Energy Wire. "Everything will now depend on whether we'll see a second or even a third wave of infections, which would deal another blow to public transport."

"Much also depends on how cities react, and if they use the opportunity to create sufficient spaces for alternative modes of transport on a large scale, such as cycling and walking. This is not only about reducing the risk of infections, but also about making people feel safer in general when they try cycling, for example," Canzler added.

Germany's transport sector has often been dubbed the "energy transition's problem child" because emissions in the sector have remained stubbornly high. The transport sector's CO2 output has been broadly stable for decades, mainly because progress through more efficient car engines has been eaten up by rising car numbers and the trend towards heavier vehicles. The uptake of electric cars has remained sluggish in Germany so far, but registration numbers started to pick up significantly this year before the crisis essentially deep froze the car market.

A blow to public transport

So far, public debates in Germany on how to respond to the crisis in the transport sector and the government’s relevant actions have focused on the rescue of airline giant Lufthansa, the controversy surrounding the proposed financial boost for the country’s carmakers and rail company Deutsche Bahn’s need for extra cash to survive. But urban public transport systems, central to urban mobility, are also one of the most prominent victims of the pandemic. According to the McKinsey Center for Future Mobility, public transit ridership has fallen 70 to 90 percent in major cities across the world due to infection fears, resulting in huge financial shortfalls for operators.

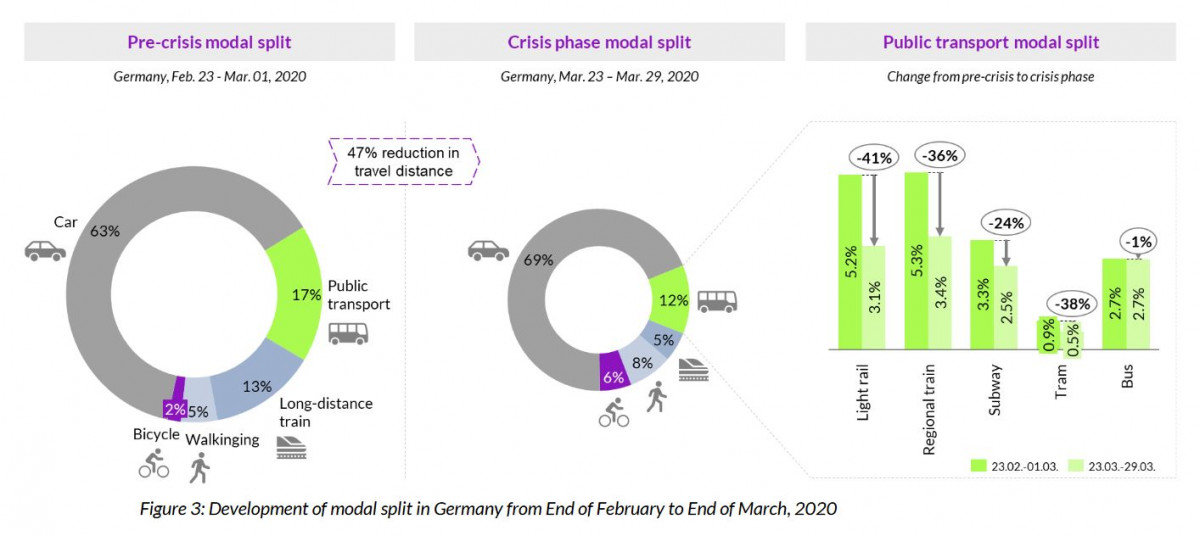

"Interestingly, the case of Germany shows that public transport was not affected evenly by the crisis. While all modes experienced a loss of ridership, buses lost riders roughly proportionally to the overall decline in mobility demand. Trains, in contrast, were hit much harder," according to the Mobility Institute Berlin (MIB).

This trend has also been observed in other regions of the world. People in China reported switching from metro to bus during the crisis because they disliked the idea of being trapped underground in a confined space, and thought they would have more options for “social distancing” on the bus, according to the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP).

Mobility experts worry that the hit to public transport could be permanent, also dealing a heavy blow to pre-corona green mobility plans. "Before the crisis, we all agreed that public transport will be the mobility transition's backbone, especially in big cities," said Lenz. "But, sadly, public transport has been hardest hit by the crisis."

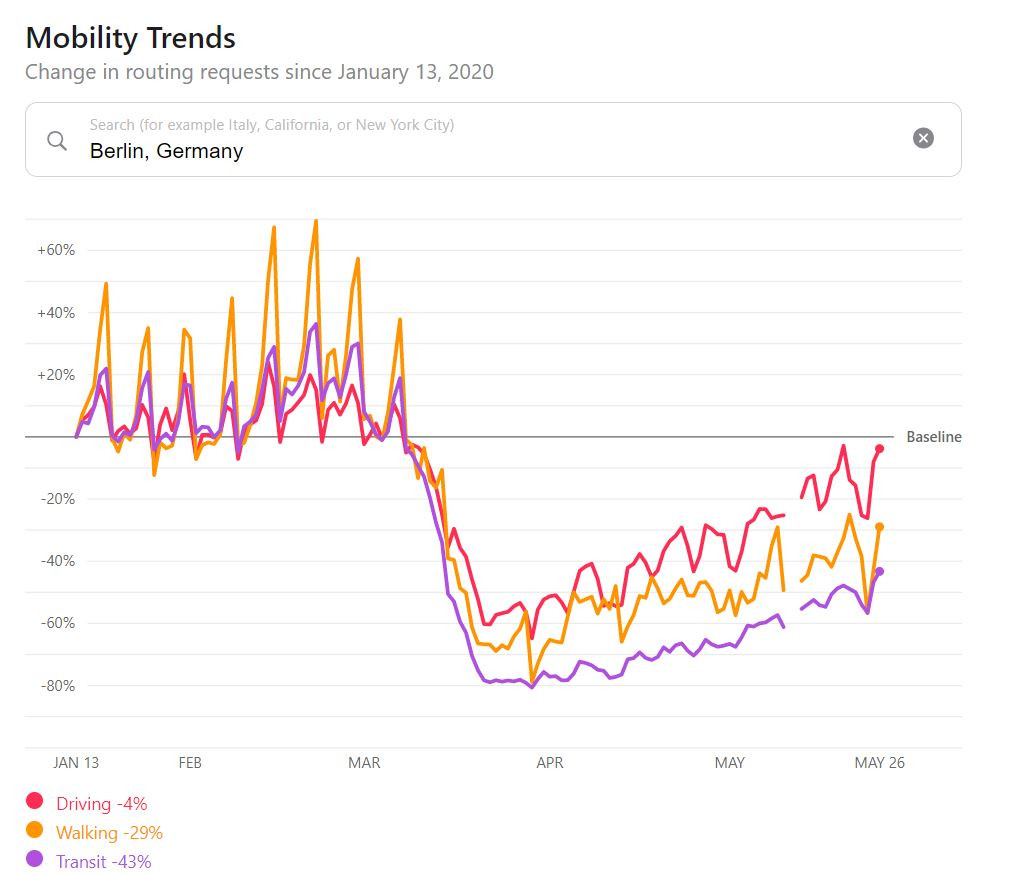

Even after the easing of lockdown regulations in Germany, the use of public transport still lagged far behind other modes of transport, according to Apple mobility data. In the city of Berlin, searches for public transport connections remained almost half below pre-crisis levels, while searches related to car use were down less than 5 percent.

Revival of private cars?

In contrast to public transport, the coronavirus crisis has added a new "feelgood factor" to private cars, which have experienced a "revival," according to a survey conducted by Lenz's institute. Around a third of respondents from German households who did not own a car said they missed one, and six percent said they were thinking about buying one.

Increased car use could push up transport-related carbon emissions in Germany by three million tonnes this year, the NGO Greenpeace has said.

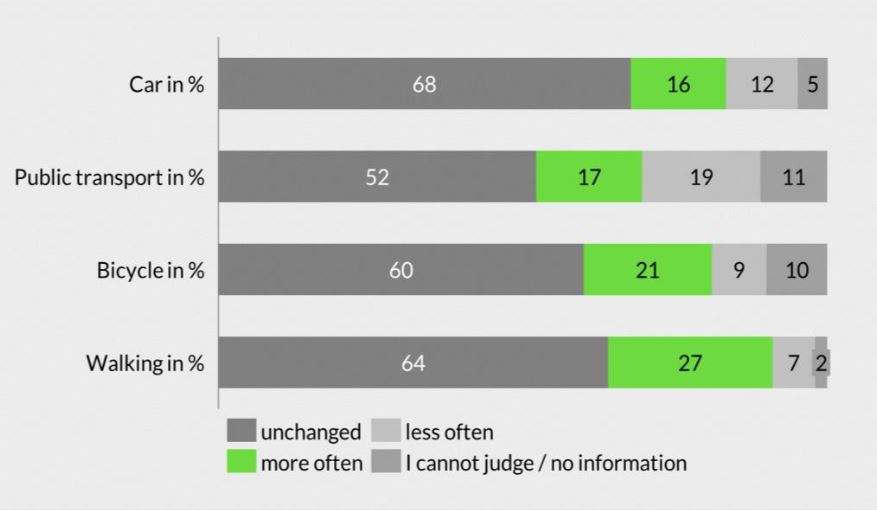

But other experts have questioned the assumption that private cars are the pandemic's great beneficiary. "While some suggest that the private car might be the big winner of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, available data seems to contradict this assumption. A recent survey among German citizens suggests that only cycling and walking might significantly gain popularity in the long term, whereas private car use may stay about the same," said the MIB with reference to a poll conducted by the General German Automobile Club (ADAC).

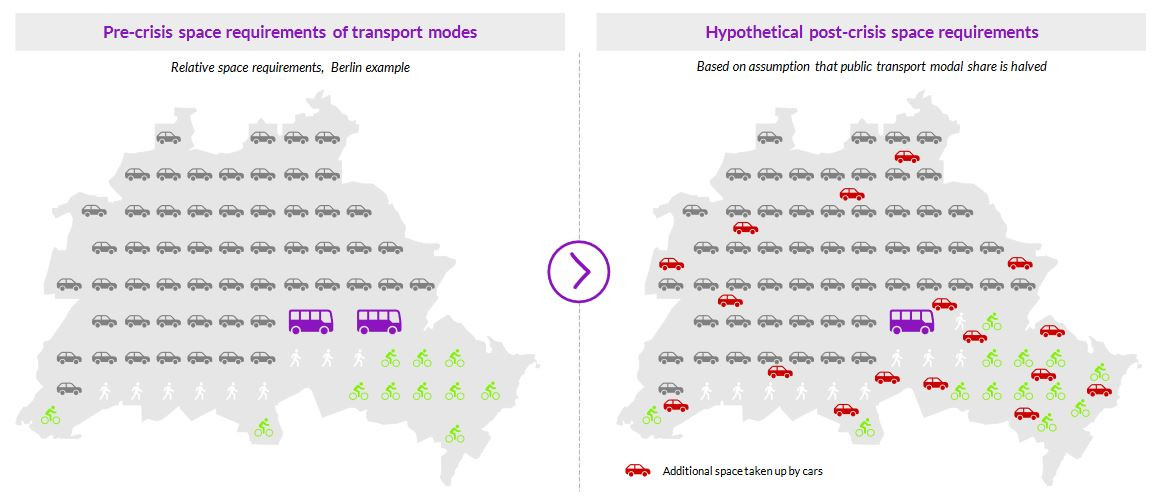

Canzler argued that a large-scale revival of cars is well-nigh impossible in cities because of congestion. "As soon as more people switch to cars, cities will become congested, and it will become more difficult to find parking spaces and so on. We will quickly hit the capacity limit that was already reached before the crisis."

Anne Klein-Hitpaß, urban transport expert at the green mobility think tank Agora Verkehrswende*, said that trust in public transport will only return if the risk of infection decreases quickly. "The danger is real that user numbers will stay down following the crisis. The problem is that transport behaviour is shaped to a very large extent by routines. People don't like changes and once they get used to new ways of mobility behaviour, there is a high risk these will get stuck."

Peak problems

Paradoxically, the crisis drastically exacerbates public transport's lack of rush hour capacities, even while heavily denting overall demand.

"The most cursory look at the average bus or train carriage shows that if you really want to maintain strict social distancing on board, you have to run at 15 to 20 percent of peak capacity — with no one standing and only every fourth seat in use," wrote Michael Liebreich, founder of Bloomberg New Energy Finance. "Urban public transport is now looking at the equivalent of chronic heart disease, with lower demand, but even lower capacity."

"If capacity is allowed to shrink more than demand, cities can expect dystopian years of congestion, gridlock, air pollution, emissions and parking shortages," Liebreich warned. "Authorities need to rebuild trust in mass transit. People need to feel safe travelling on trams, trains and buses even before the virus has completely disappeared."

The DLR's Lenz told Clean Energy Wire the capacity drop due to social distancing during rush hour is public transport's "ultimate problem," adding that it remains utterly unclear how to overcome this dilemma. "Of course, we could have more vehicles and more personnel to drive the vehicles, and we could extend existing infrastructures and establish new lines. But all of these approaches are no quick fixes." [Read the full interview with Lenz here.]

Germany's transport operators also say that a rapid expansion of capacities is impossible. "If we had to maintain the distance of 1.5 metres with the usual number of passengers at peak times, we would need four times the number of rides on offer today," the Association of German Transport Companies (VDV) told Spiegel magazine. "Even if financing were possible, short-term implementation would fail because there are too few staff and too few vehicles available."

In federal Germany, investments in public transport largely depend on local authorities, many of which were already strapped for cash before the crisis hit, and now face an additional collapse of tax income. This is why a study commissioned by the environment ministry said that enabling local authorities to invest in sustainable transport must be a central element of a green stimulus package.

Most experts believe that public transport operators have only limited options to regain trust. "A feeling of cleanliness and hygiene is extremely important now to restore confidence. For example, why not provide hand sanitisers for public transport users?" asks Klein-Hitpaß. "Users need to feel that public transport is clean, even if it doesn't make that much of a difference for the real risk of infection."

Home office a solution?

Public transport's rush hour problem might be attenuated if many people choose to work from home following their lockdown experience in the home office. If the average employee continues to work remotely one day per week, daily commutes would drop 20 percent. Germany's labour minister Hubertus Heil has said he wants to enshrine the right to work from home into law by autumn. He said first estimates suggested that the share of employees who work in a home office has risen from 12 to 25 percent during the crisis.

In the longer term, it might be possible to resort to digital tools to make people feel safer, for example using an app that provides real time alerts if undergrounds are crowded, according to Klein-Hitpaß. "Another option might be to develop the necessary infrastructure so people can book a seat on the underground or the tram," she added.

Notwithstanding the numerous problems the pandemic has created, experts still agree that public transport remains absolutely central for making urban mobility sustainable.

"Should we reconsider the strategic importance of public transport in urban mobility? The simple answer is ‘no’. There is no alternative to public transport in urban mobility," argued the MIB, adding that a substantial increase in car use would overburden public urban space.

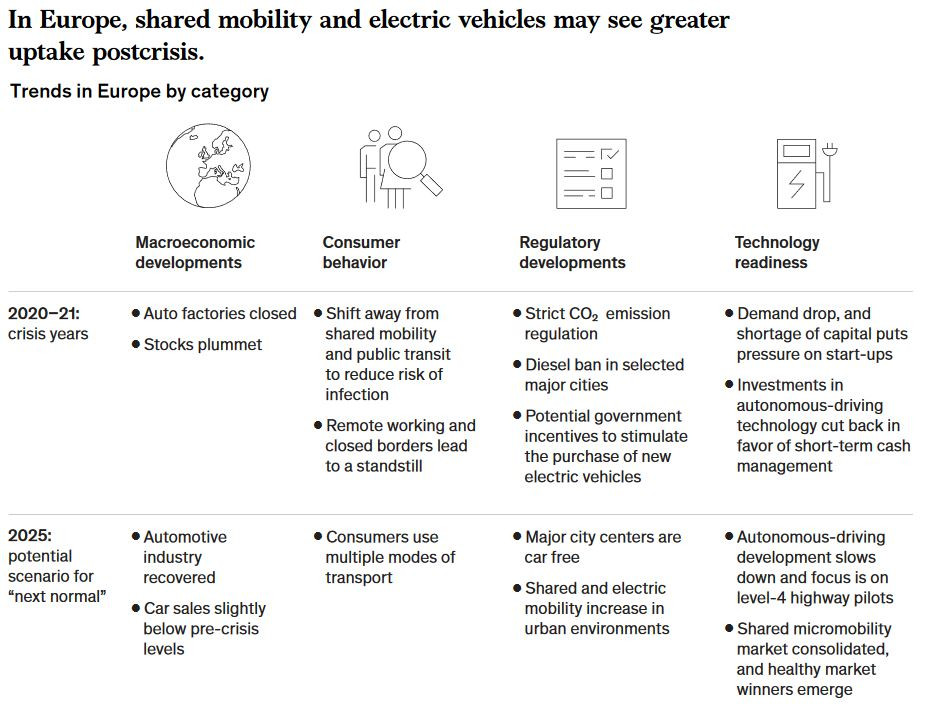

The McKinsey Center for Future Mobility has not given up hope that public transport will recover from the crisis. "At this point, we believe many changes in the modal mix are temporary and that shared mobility solutions, including public transit, will rebound and continue to capture an increased market share."

But the MIB warned that mobility demand is set to remain volatile as long as there is no vaccine against the coronavirus, possibly leading to a back-and-forth of restrictions, which could repeatedly shake up people's transportation habits. "People are likely to get used to a more flexible way of choosing different transport modes from day to day."

Pandemic could delay autonomous cars

The pandemic is having a significant impact on people's choice of transport mode, but it could also delay the arrival of autonomous cars, which play a central role in many scenarios for future urban transport in the form of robotaxis that could replace a large number of private cars.

"Over the short to mid-term, the COVID-19 crisis could delay the development of advanced technologies, such as autonomous driving, as [carmakers] and investors scale back innovation funding to concentrate on day-to-day cash-management issues," argued McKinsey.

But the consultancy also said that autonomous cars and micromobility solutions like electric scooters "could see higher-than-expected demand, since they enable physical distancing. […] We believe that customer demand for these solutions could soar once the initial crisis subsides, increasing their attractiveness to investors."

Boost to cycling

Disregarding future high-tech solutions like autonomous cars, the pandemic has given much simpler and already existing forms of clean mobility a big boost: Cycling and walking.

"At least the corona crisis arrived at the right time of the year in Germany, because it allows people to try cycling," said Klein-Hitpaß. "Many will find out that it is a quicker and nicer way to get to work – additionally, they can keep fit while the gyms are closed. A lot more people could switch to bicycles because most commuting distances are really short."

Cities all over the world have already given pedestrians and cyclists more space so they can move around more safely with a reduced risk of infection. "For example, Bogotá, Colombia, has added 76 kilometres, or 47 miles, of cycle lanes to encourage physical distancing. Other cities, including New York City, have closed several streets to traffic. In Oakland, California, an astounding 74 miles of streets — 10 percent of the total — have been blocked off so pedestrians and cyclists can remain six feet apart," said McKinsey. "We assume that some of those measures might remain in place after the crisis. If they promote improvements, such as fewer accidents and less pollution, cities may decide to make them permanent."

Other European cities like Milan and Brussels have also banned car use in certain areas. German cities have not gone that far, but some have granted cyclists more space during the pandemic. The capital Berlin has installed "pop-up bike lanes" by converting entire car lanes to cycle paths.

"Half a year ago no-one would have thought it was possible to establish these pop-up bike lanes on major Berlin roads," said Canzler. "I think these examples will massively increase the pressure on other districts and cities to catch up. But some major cities like Hamburg or Cologne have been very reluctant to use this opportunity to boost cycling."

Nine percent of Germans said that during the pandemic they considered buying a bicycle or an electric bicycle, a higher share than those thinking about a car purchase, according to the DLR survey.

Extraordinary times demand extraordinary measures

Pop-up cycle lanes show that the pandemic also offers an opportunity to further the clean mobility agenda in cities.

"This is a window of opportunity to address urgent infrastructure problems that slow the shift to green mobility," said Klein-Hitpaß. "Often a lack of courage slows down forward-thinking urban mobility planning. The crisis has given local administrations the chance to say: 'Okay, we have an extraordinary situation to deal with, which allows us to take extraordinary measures.' This approach has resulted in pop-up cycle lanes, and temporary play streets because people need to go outside, and they need space to spread out. The crisis is a good opportunity to redistribute urban space by taking some away from cars and giving it to buses, cyclists and pedestrians. This is particularly important because we also need to think of all the people who don't even own a car – this is also a question of justice."

Berlin is Germany's city with the lowest level of car ownership – 51 percent of households don't have one.

But the DLR's Lenz said that most additional cycling and walking spaces remain far too fragmented to have a big impact on overall mobility. "What would really get us forward would be proper pop-up networks instead of single pop-up lanes. We've known for a long time that genuine networks are key to boosting walking and cycling. And, sadly, I don't see that happening at present."

Liebreich argued that local authorities should use the momentum and "massively increase rental bike capacity," and set up bike and scooter parking and charging locations, while discouraging the use of private cars.

'Sharing is caring' -- no more

While giving a boost to cycling, the corona crisis has also hit new forms of shared transportation hard, such as car sharing or ride pooling.

"There is a real danger that the crisis deals a fatal blow to some car sharing services. New mobility providers will have a very hard time coming to terms with the fact that the crisis has rendered the idea that 'sharing is caring' obsolete," says Klein-Hitpaß. "This is a real shame as these new services had only been at a fledgling stage even before the crisis."

New urban mobility services were forced to react drastically to the crisis in Germany. Berlin-based ride-sharing service Berlkönig, for example, closed its regular service. Some operators of shared e-scooters, such as Lime, terminated their service altogether.

McKinsey was also pessimistic about the prospects for many young companies with a sharing-based business model. "Some governments have launched initiatives to support mobility start-ups that were hit hard by the crisis, but low cash reserves and a lack of capital in the market will most likely take their toll on many players. Just recently, a scooter-sharing start-up laid off over 400 employees (30 to 40 percent of its workforce)," said McKinsey referring to scooter start-up Bird, which also operates in Berlin.

Many transport experts believe the way forward for some shared service providers is closer-knit integration with public transport systems. "The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic opens a crucial window of opportunity for negotiating multi-modal integration. Many new mobility players are suffering from the pandemic too. This might increase their willingness to discuss a more thorough integration into city-wide collaboration schemes that do not exclusively focus on clustering their services and assets in city centres," wrote the MIB.

Bookings via the Berlin public transport provider BVG's mobility App "Jelbi" show the essential value added by multi-modal integration in navigating the pandemic, according to the MIB. "Between January and April 2020, the app experienced a 90 percent decline in public transport bookings. At the same time, however, the booking of shared services increased by 6 percent with a focus on shared bikes."

Sliding backwards?

On balance, most mobility experts are holding out hope that the crisis might delay the shift to green mobility at worst, but will not derail it. "My overriding impression is that the issues of climate protection and the corresponding mobility transition are not forgotten during the crisis," said Lenz.

The central role of sustainability in discussions about measures to stimulate the economy indicates that public investments in transportation might well be used to further the shift to clean mobility and to finally get the sector on track for Germany's climate targets.

Klein-Hitpaß also considered it essential for clean mobility to remain on the policy agenda regardless of the crisis. "The transport transition was widely discussed in German society before the crisis hit. The aim must be to keep this discussion alive – not despite the crisis, but because of it. We need to make sure we don't end up sliding backwards."