COP21 - Day 7/8: A German facilitator, a climate action plan 2050

The ministers and top-officials from 195 countries have found themselves with “a lot of work” for the second and decisive week of the Paris climate summit, Germany’s environment minister Barbara Hendricks said as she was taking over leadership of the German delegation. There were for example still “bitter arguments” over the issue of differentiation. The United States insisted on a change in the current regime of dividing countries in industrialised and developing countries, a position shared by the European Union. A solution was “indispensable” to reach a deal, and the disagreements in this field spilt over into areas such as climate finance, she said.

An ambitious schedule

French foreign minister Laurent Fabius has now put an ambitious timetable out, Hendricks confirmed. His target was to have an agreement ready by Wednesday morning, which will then be finalised during the day. The text would then have to be translated from English into the other five UN languages. On Friday, Fabius wants to have the deal done.

The French COP presidency, which has now taken charge of the negotiation procedure, appointed German environment state secretary Jochen Flasbarth as one of 14 facilitators “to ensure the success of COP21”. Flasbarth will co-head the round table on implementation mechanisms on financing, technologies and capacities. “The German role in the negotiations is that we are on the one hand actively promoting an ambitious agreement and on the other hand we are a trustworthy partner for finding compromise in the negotiations,” said Hendricks. Hendricks herself will co-lead talks for the EU regarding the topic of differentiation.

“There is still a lot of work ahead of us, I will have bilateral talks with many countries to build alliances for an ambitious result,” Hendricks said. Among the most important allies were the small island states. For their sake, Germany was continuing to push for a mention of a 1.5°C warming limit in the treaty. Such a mention would not replace the 2° limit as the overall long-term goal, Hendricks stressed. But it was important to show that some states were suffering from the impact of climate change even if the world community succeed in keeping global warming below 2°C. The US was “not disinclined” to the idea, but Saudi Arabia was in strong opposition, Hendricks said.

Germany is supporting small island states like the Marshall Islands and Tuvalu with the IRENA SIDS-Lighthouse initiative to help a transition to renewable energy sources with 3 million euros between 2015 and 2017, the environment ministry announced. Eventually the initiative is to reach $500 million overall.

Martin Kaiser from Greenpeace Germany said he saw Flasbarth in a good position to facilitate the round table on finance because of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s announcement to double the country’s climate finance contribution to 6 billion euros by 2020. This was showing the right form of commitment to developing countries, he said. Kaiser also applauded the French’s tough timetable. Everything that helps to put pressure on the negotiations was helpful, as was a clear structure.

Decarbonisation or climate neutrality?

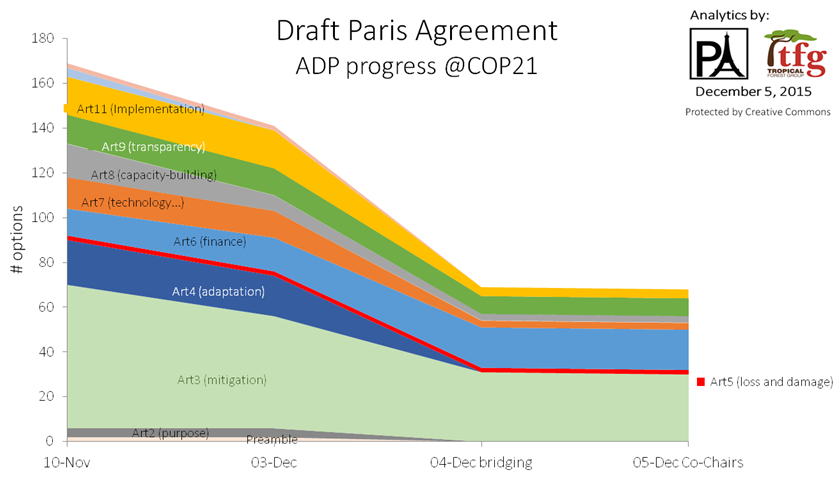

Despite the overall amount of brackets and options in the text decreasing (see graphic below), ministers still have a lot of alternatives to fight over. “Depending on what they do with the options on the table, the deal could be strong and ambitious or watered-down and ineffective,” Climate Action Network (CAN) writes. Apart from differentiation and finance, the long-term goal and the review mechanism were contentious issues, the German delegation said.

The EU and the US are still strongly in favour of seeing every country “in a position to do so” to participate in climate finance. The new treaty was to last till the end of the century, commissioner Miguel Arias Cañete said. By then, some countries who are poor now will be rich, so the new treaty has to account for such future changes, he explained.

Hendricks reckons that either “decarbonisation” or “climate neutrality” will be the long-term mitigation goals. With regard to the ambition mechanism, 2021 as the first year to start a review period could be a compromise in current debates, that she “could live with”, Hendricks said.

Climate action plan 2050

The German government aims to adopt a climate action plan for 2050 next year, Hendricks said at an event in Paris. The climate action plan 2050 will make it easier to plan the future and will provide solid basis to decarbonising our economy,” she said. An ambitious result at the Paris summit would support the process, which started with a civil society dialogue earlier this year, she said. “We aim to adopt the Climate Action Plan 2050 next year – and then start to implement it.”

Hendricks reiterated that the country had to end energy supply from fossil fuels, including lignite. “We need a roadmap which clearly indicates that the area of lignite will end, and at same time offers regions a perspective,” she said.

Some German industry representatives have already voiced opposition to a 2050 climate action plan. The Federation of German Industries (BDI) demanded in its half-year assessment of government policies published before the Paris summit, that the government “drops” the idea. There were too many climate plans on too many levels (European, federal, states), sometimes with incoherent targets, the association argued.

But economist Lord Nicholas Stern from the London School of Economics (LSE) said that climate action and a successful economy was not a contradiction anymore. Speaking at an event in Paris, Lord Stern said that as long as governments introduced policies that gave “a clear sense of direction and clarity”, this would give confidence to industry. “It would be wonderful if Germany set a not-too-far-away target for phasing out coal completely,” he added.

Energy transition – from Germany to Africa

A group of industrialised countries have pledged $10 billion to The Africa Renewable Energy Initiative. Germany will contribute 3 billion euros to the initiative which aims to install an extra 10 gigawatt of renewable energies in Africa by 2020 – by 2030 the capacity is envisaged to increase to 300 gigawatt. 600 million people in Africa don’t have access to electricity. “Africa has a large appetite for energy. We now have to prevent that this appetite is satisfied with coal, oil and gas,” Minister Hendricks said.

Annalena Baerbock, speaker on climate policy in the oppositional Green Party in parliament, said that Germany’s whole export policy in the energy sector had to become 100 percent renewable. “Important pledges for supporting renewable development in Africa should not be thwarted by supporting coal power abroad at the same time,” she said.