Bavaria struggles with crucial decision on power lines

The southern state of Bavaria has once again postponed a crucial decision over the next step in Germany's energy transition. Following a three-month “Energy Dialogue”, Bavaria’s energy minister, Ilse Aigner, announced that the federal government in Berlin should decide whether electricity “superhighways” are needed to bring power the southern state.

The proposed grid extensions would transport renewable power from wind turbines in the breezy north of the country to energy-hungry industries in the south, home of BMW and industrial conglomerate Siemens. The issue has become a stumbling block for the Energiewende, the transition to a low-carbon energy future. Today, much of the electricity consumed in Bavaria is provided by nuclear power stations which are slated to be shut down by 2022.

Many experts believe two maximum-voltage grid extensions are needed to address the disparity between over-supply in the north and the threat of under-supply in the south. But the prospect of pylons twice as high as conventional overland lines running past their houses, has driven many locals to protest the superhighways, and state premier Horst Seehofer has publicly questioned the need to extend the grid.

In July 2014 he announced that the “free state of Bavaria does not want power lines”. Instead, Seehofer wants gas-fired power stations to make up the shortfall when nuclear power plants are taken offline. There is only one problem: Those power stations are economically not viable, which means they won’t be built without state subsidies.

Bavaria had in principle already agreed to the building of the superhighways during the federal planning process. But Seehofer, who leads the CSU, the Bavarian sister party to Chancellor Angela Merkel’s CDU, changed his mind in the face of protests, which gained momentum as the proposals became more concrete and the locations more precise.

The planning process for the grid extensions is fluid and updated on a regular basis, giving Bavaria – the federal state where Merkel will host the G7 meeting of industrialised countries in June – considerable influence on the process.

The Energy Dialogue was meant to clarify Bavaria’s options. But energy minister Aigner didn’t answer the crucial question of whether one, two – or none – of the grid extensions were needed. In her concluding remarks to the massive round table, she said only: “The formula is two minus X. How big the X will be depends on decisions taken in Berlin.”

Aigner also suggested it would be possible to reduce Bavaria’s need to import energy through measures including minor changes to the existing grid and increased efficiency. “It is not our duty to solve the problem of over-supply in north and central Germany with new power lines,” Aigner said.

Bavaria faces growing frustration with its current role in the Energiewende. Grid operators and industry warn of impending electricity shortages. “The recent escapades of the Energiewende remind me of a plane that takes off without knowing whether there is a landing strip at the end of the journey,” Lex Hartman, head of grid operator Tennet, told the Süddeutsche Zeitung.

The German Renewable Energy Federation suspects Bavaria’s indecisiveness is mainly motivated by tactical manoeuvring and warned: “Grid shortages owing to politics could cost citizens and companies dearly in the medium term.”

The patience of central government in Berlin is also wearing thin. Alluding to the colours of the Bavarian flag, Urban Rid, head of energy policy at the economy ministry, recently remarked, “There are no white-and-blue electrons and there is no white-and-blue energy transition.” His boss Sigmar Gabriel, Minister for Energy and Economic Affairs, has even warned that Bavaria might pay for a “no” to the extensions with higher electricity prices.

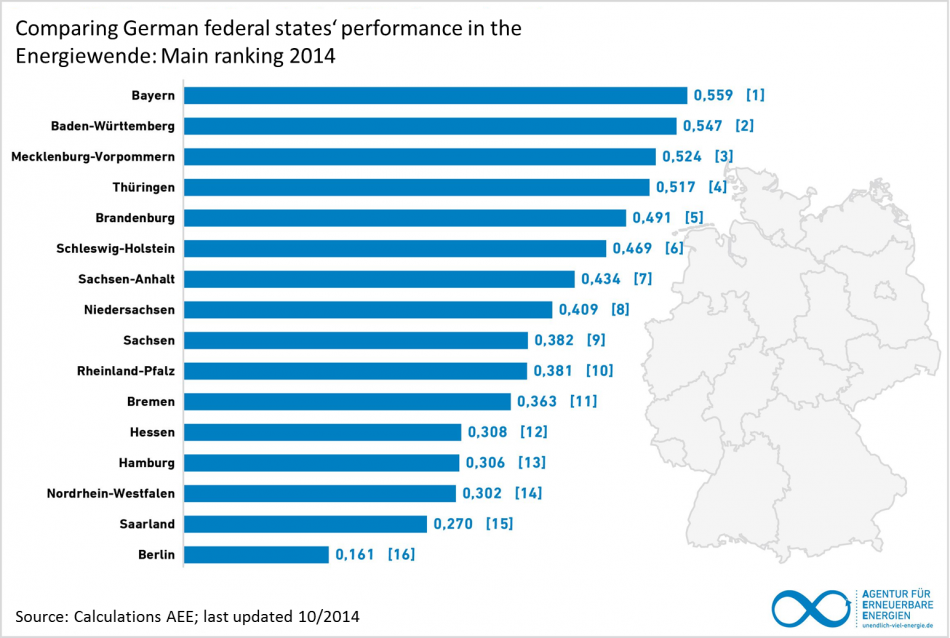

A large majority of Germans still support the Energiewende and Bavarians are no exception – despite the recent protests. On many counts, Bavaria is even a poster boy of the whole project: A third of its power comes from renewable sources, more than the national average, and around 66,000 people make a living from renewables there, more than anywhere else in Germany.