Auction scheme for solar installations ushers in new phase for renewables market

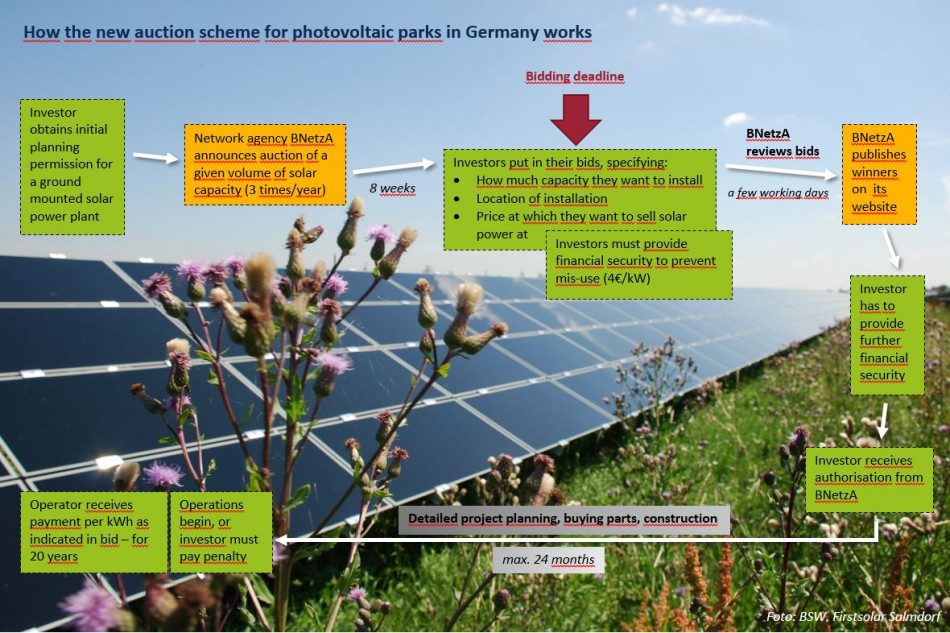

Support for the large-scale solar facilities will no longer be offered at pre-set “feed-in tariffs,” the 20-year, guaranteed price for every kilowatt-hour of electricity produced. The tariffs have been an integral part of boosting renewables in Germany’s Energiewende, the transition to a low-carbon economy, since the Renewable Energy Law (EEG) was passed in 2000. But as the market matures, alternatives like the auction system are under consideration. Under the solar pilot scheme, companies will have to bid for financial incentives.

The new auction system takes aim at several goals – coming to grips with the cost of the Energiewende, introducing market elements, meeting European Union competition demands, and ensuring that solar parks are well-distributed and do not displace arable farmland or conservation areas.

The bidding scheme should make it easier “to reach the development goals for renewable energy in a plannable and more cost-effective manner,” the government said in a press release.

Solar plant operators will bid to install a certain capacity (between 100 kilowatts and 10 megawatt), specifying the feed-in payment they want to receive for each kilowatt-hour they produce. The German network agency sets a maximum value for the auction, based on the current feed-in tariff, and the lowest bidders are awarded contracts. Winning bidders must sell their power directly on the market, but will receive a “market premium” to make up for any difference between the average monthly power exchange (EPEX spot) price and the fixed feed-in payment awarded. The payment is guaranteed for 20 years under the new regulation passed by the government this week.

Companies have also had this option to sell their power directly in the past. In 2013, around 80 percent of onshore wind facilities and 11 percent of solar opted for this.

Testing it on solar power

Hauke Hermann, energy expert at the research group Öko Institut in Berlin, told the Clean Energy Wire that the pilot is “basically well suited to the solar sector.” This is because the size and homogeneity of the open-space installations provide the basis for a small, competitive example. “We are going through a period of change, so it is good that the pilot is being carried out,” he said.

Licenses for a total of 1200 megawatts of power for new installations will be auctioned in multiple rounds: 500 in 2015, 400 in 2016 and 300 in 2017, the government said, confirming plans outlined in 2014. Bidders offering the lowest price will be awarded the subsidy, as long as the total bids exceed the amount tendered.

The first 150 megawatts will be auctioned starting in February and tenders will be accepted until April 15. That will be followed by 150 megawatts on August 1 and 200 megawatts on December 1. If total bids fall short of the amount tendered, all bids will be accepted. Later, these amounts can be adjusted, depending on the results of the previous auction. In order to encourage a large number of bids, tenders will be limited in size to between 100 kilowatts (500 in 2015) and 10 megawatts, and a single bidder may submit multiple offers.

Öko Institut’s Hermann pointed out that incentives for solar power had fallen so low in recent years, and little was currently being built. Limiting the volume of solar power coming on line and introducing more competition may give the market some impetus, he said. “I am very interested to see what the results are,” he said. “It’s hard to imagine that anything could be cheaper than it is now.”

In November, the number of new installations had sunk by 43 percent over 2013, the economics ministry said. In 2014, around 600 megawatts came on line.

More competitive or too bureaucratic?

The German government says it has taken care to ensure the auction helps allocate subsidies more efficiently, by balancing the volume auctioned and the area allocated for installations. That should create a competitive situation and reduced costs, a spokesperson from the economics and energy ministry told the Clean Energy Wire.

The BDEW German Association of Water and Energy Industries Association praised the scheme’s competitive structure. President Hildegard Müller said in a statement that it would “encourage a broad diversity of bidders,” and called it “a good basis for collecting initial experience with auctions for renewable energies.” The BDEW was particularly pleased that the government had avoided giving some participants advantages over others in the bidding process. But it was unhappy that the government had not lifted restrictions on solar park locations. Subsidized facilities will remain limited to land alongside motorways and train tracks or converted properties like former military grounds.

Germany’s Solar Energy Association was far more critical, saying the amount of power being auctioned is too small and and locations too limited, calling the procedure “too bureaucratic.” “The planned auction volume for open-space solar installations is not enough to meet the government’s target for new photovoltaic installations,” it predicted. “Even though electricity prices from solar parks have begun to fall, further expansion in Germany will now be reined in and capped,” the association said.

By capping the volume of solar power eligible for subsidies, the government aims to eventually limit the amount of new power from all types of solar facilities to 2.4-2.6 gigawatts a year. This should help optimize the use of subsidies. Before the renewables law was changed in 2014, solar feed-in-tariffs were slated for phase-out when capacity reached 52 gigawatts – expected around 2017. Current installed capacity is around 38 gigawatts. The economics ministry said this will depend on the result of the pilot auctions. Solar parks built prior to 2015 will still receive their guaranteed payments in line with the previous law.

The tariff for solar open-space installations has been cut dramatically since they were introduced, down from around 50 cents per kilowatt hour in 2000 to below 9 cents in 2015. Even with the adjustments, tariffs for renewables and the surcharge consumers pay to fund them have been seen as driving costs higher in Germany since their introduction. Consumers pay the difference between the market price for power and the higher feed-in tariff for renewables – to the tune of 24 billion euros a year, according to the Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Energy.

Unknown effects on renewable development

Caps and a bidding process are also in the works for wind and other renewables, but are not expected until 2017. The government hopes to learn from the experience of the solar auction what would work best for the other sectors.

But the German Wind Energy Association, BWE, said it was sceptical. “For us it is clear that there can be no 1:1 transfer to other types of energy production. For onshore wind, experiences in other countries have shown that the government’s goals of cost efficiency, targeting and diversity of participants are rarely achieved,” said Hinrich Glahr, vice president of the BWE.

The government would also like to usher in a gradual shift to a more market-based system for renewables. In a publication explaining changes to its renewable energy law, the economics and energy ministry said it expects the changes to the subsidy system will eventually reduce the average support per kilowatt-hour for all renewable energy to around 12 cents as of 2015 from 17 cents previously.

Critics have worried that the shift away from this key component of Germany’s Energiewende will stymie development of the renewables sector and even whittle away at the project’s very core. Oliver Krischer, Green Party parliament member, says that the government “is further putting the brakes on the expansion of renewables,” and calls the model a “bureaucratic monster that destroys the diversity of participants” in the auctions.

But the government argues that the need to wean the industry – which now produces nearly 30 percent of Germany’s electricity, up from around 7 percent in 2000 – from subsidies is a sign of the Energiewende’s very success and a natural progression for a maturing market, according to their publication. The government says it is confident that Germany will reach its goal of a 40-45 percent share of renewables in the power mix by 2025 and 55-60 percent by 2035.

The government will present its findings and recommendations from the pilot project to parliament on 30 June 2016.

![© [il-fedexl] - Fotolia.com](https://www.cleanenergywire.org/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_image/public/fotolia_46459228_il-fedexl.jpg?itok=yCsom9ou)