Industry power prices in Germany: Extremely high – and low

Energy transition pushed up power prices – and lowered them

Germany is known all over the world for its export prowess and its strong manufacturing sector. Industry's share of the country's economy is almost 23 percent, compared to an EU average of about 16 percent. The importance of the sector – which employs more than seven million people and includes global brands like carmakers BMW, Daimler and VW, chemicals maker BASF and engineering conglomerate Siemens, among many others – makes the impact of the energy transition on manufacturing companies a hot issue in Germany, with electricity prices at the focus of many debates.

But while industry associations regularly warn that power price increases triggered by the energy transition pose a threat to competitiveness, critics retort that industry complaints are often exaggerated and that many companies even get their power too cheaply. Can both be right? The energy transition's effects on industry prices of electricity lend support to both views.

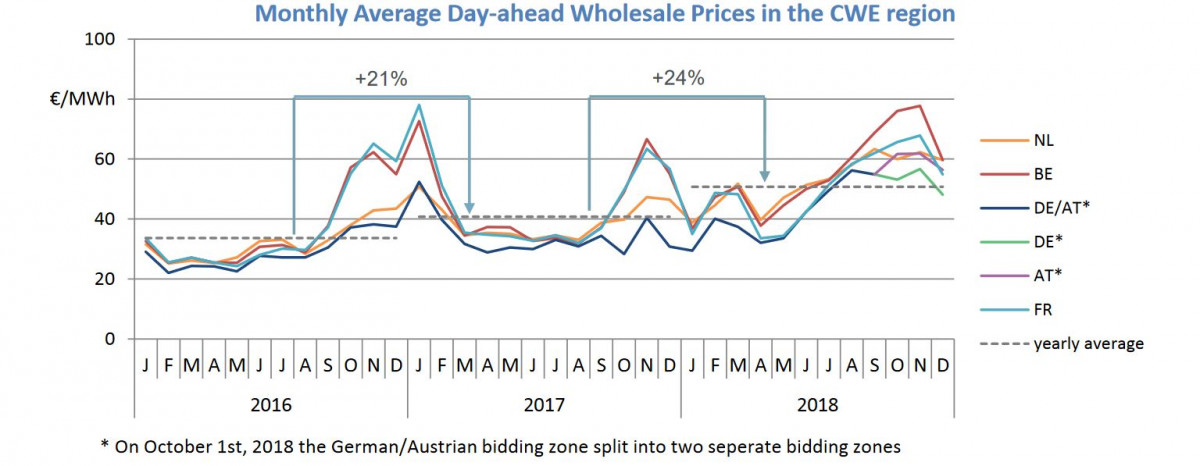

In a nutshell, the roll-out of renewable energies on a huge scale has had two opposite effects on power prices in Germany. On the one hand, cheap renewable electricity flooded the power market, pushing down wholesale power prices (see the factsheet on the so-called merit order effect for details). This mainly benefits large and energy-intensive industrial companies, because many can basically source their electricity at wholesale prices.

On the other hand, the capital-intensive deployment of renewables pushed up power prices for everybody else – namely households and less energy-intensive companies that can't buy their electricity at wholesale prices. This is because Germany mainly finances the roll-out of wind turbines and solar arrays, as well as the modernisation of the grid, with numerous fees and levies that are added to wholesale power prices and paid by consumers with their bills - except for the companies that benefit from exemptions of various degrees.

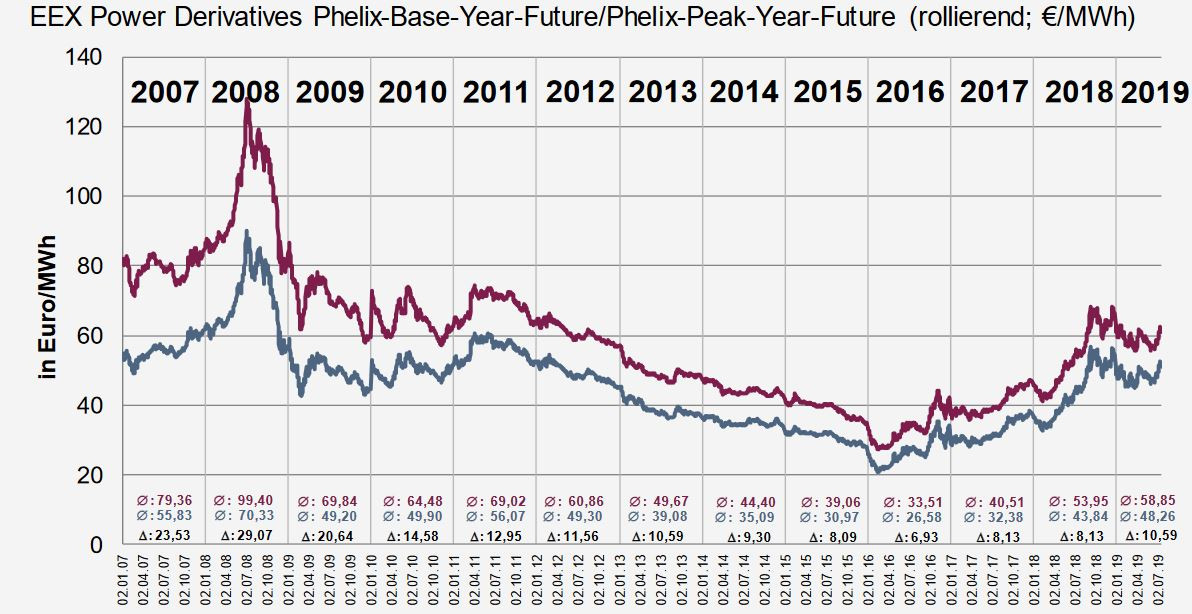

The following two graphs illustrate these opposing effects of the energy transition on power prices in Germany. The first traces the development of wholesale power prices and clearly shows the downward trend when the energy transition gathered pace around ten years ago (the recent uptick is a Europe-wide phenomenon mainly caused by rising prices for CO2 allowances in the European Emissions Trading System ETS):

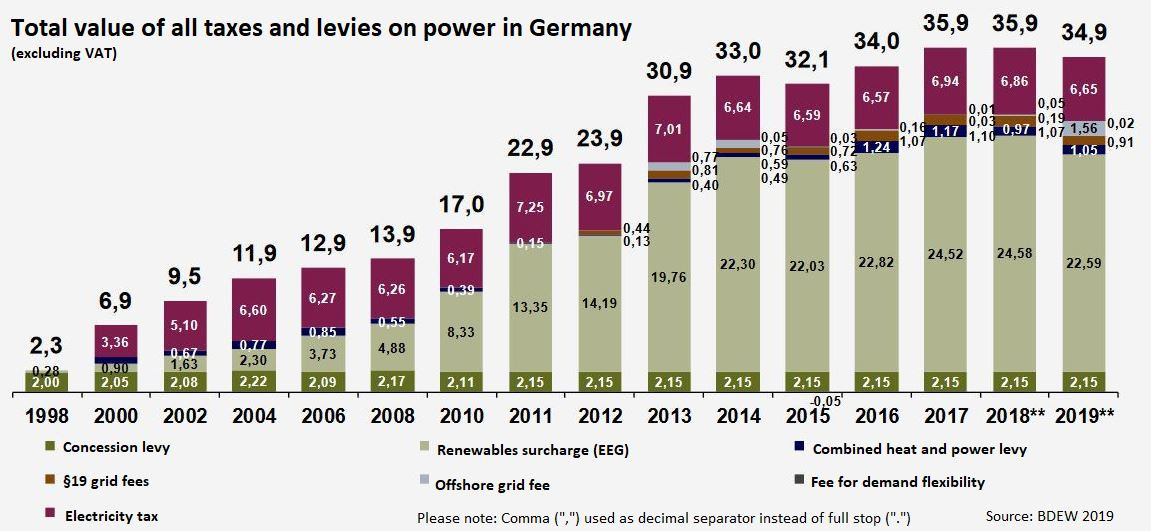

In contrast, the graph below illustrates the growth of taxes and levies on power prices, mostly used to finance the capital-intensive renewables roll-out:

"The best and the worst in the world"

Since there are a number of ways to generate power and the variety of levies and exemptions is bewildering, companies pay an extremely wide range of prices for power in Germany. They can buy it on the exchange, directly from utilities, or operate their own plants. The price also depends on how much energy they use, when they use it, whether demand fluctuates or is stable, their proximity to production plants, whether they are connected to the high, medium or low-voltage grid, and whether they compete on international markets.

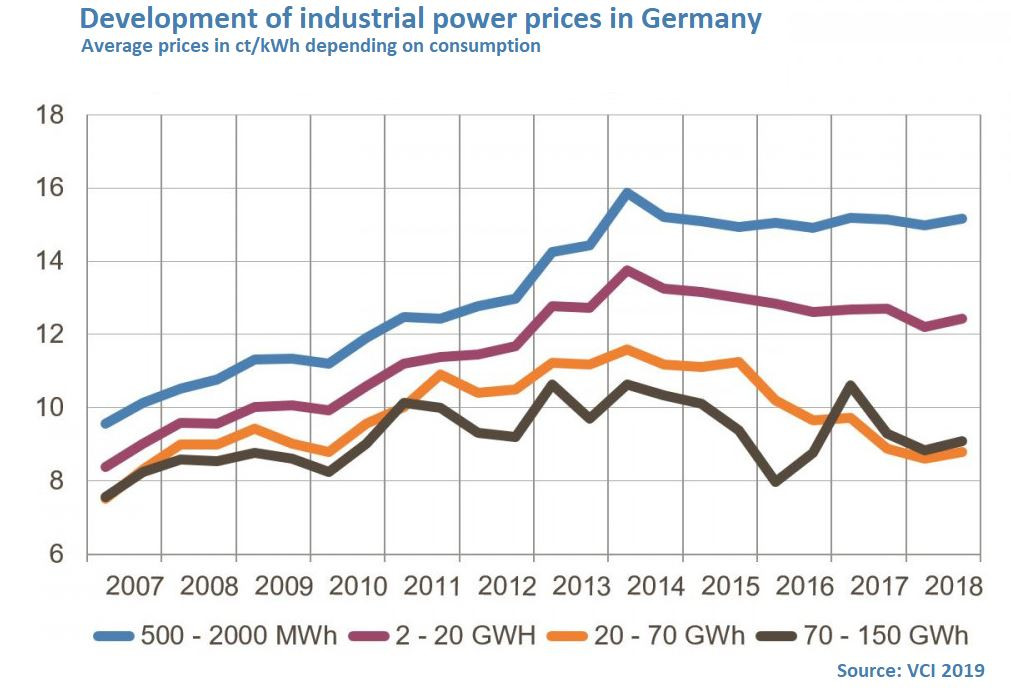

Even among large industrial users, some companies pay more than three times the price charged to others. Depending on the exemptions from taxes and levies, a large, energy-intensive company using 100 million kilowatt-hours (kWh) per year paid anywhere from 5.1 cents/kWh to 17 cents/kWh in 2018, according to utility association BDEW.

On average, industrial companies paid 15.98 cents/KWh in early 2019, an increase of 0.68 cents/kWh compared to a year earlier. This was due to rising wholesale prices, according to the latest monitoring report drafted by Germany's grid agency (BNetzA) and the Federal Cartel Office.

"On a graph comparing industry power prices around the world, you can find Germany twice: the best in the world, and the worst in the world," says Claus Beckmann, who heads energy and climate policy at BASF. Because the company benefits from many industry exemptions, it pays comparatively little for the electricity it needs.

Independent think-tanks confirm Beckmann's observation. "The sweeping statement that 'Germany's industrial power prices are high' or 'they are low' is always wrong," says Fabian Joas from the energy transition think tank Agora Energiewende*, who co-authored a study on the decarbonisation of energy-intensive industry.

The wide spread of power prices also explains seemingly contradictory business complaints. On the one hand, small and medium-sized industrial companies lament that high power prices in Germany are “a killer for our competitiveness,” because many of them indeed pay relatively high prices. On the other hand, Germany's low wholesale power prices benefitting the largest consumers have led to accusations by neighbouring European countries that Germany distorts competition by supplying its industry giants with unfairly cheap electricity.

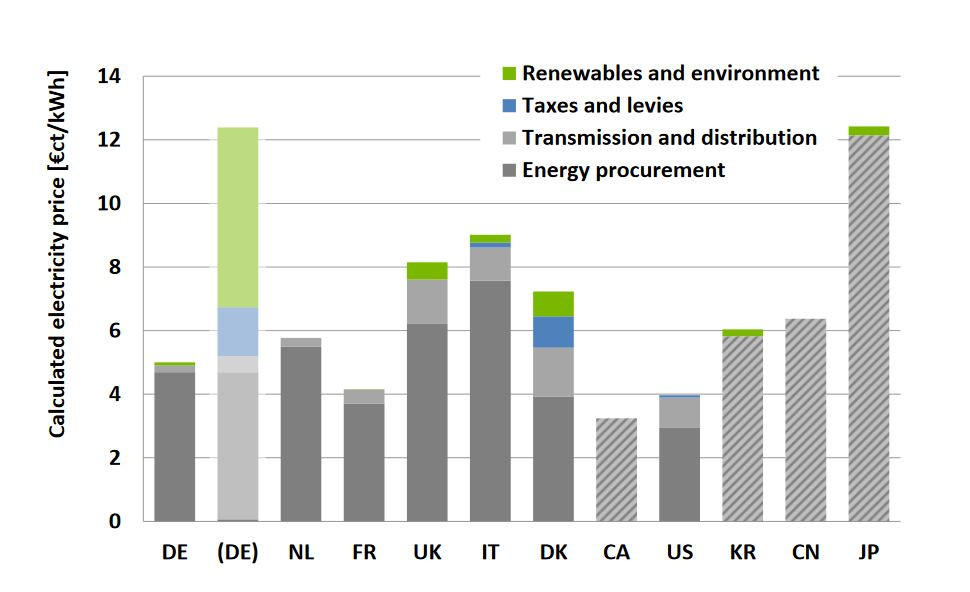

High power prices pose a particular problem for Germany's famed Mittelstand – the country's huge number of small and medium-sized businesses that are often family-owned, can be highly innovative, and form the bedrock for Germany's industrial sector. The graph below clearly indicates the wide price spread between smaller businesses and the largest electricity consumers.

In contrast, large companies enjoying maximum exemption from taxes and levies pay low rates for electricity in an international comparison because wholesale power prices are consistently lower in Germany than elsewhere in Western Europe, mainly due to the impact of renewables mentioned earlier. The following graph by grid operator Tennet shows a comparison between German wholesale prices and those in other countries in Central and Western Europe.

Lowering energy bills by using less

Analyses of German power prices and their effect on industry are also much complicated by the fact that electricity costs are not only determined by prices but also by the amount consumed. Furthermore, electricity is only one component of companies' energy costs – prices for gas, oil and coal are also decisive for many businesses.

"It is the overall cost of energy (not just the price) which is important when it comes to understanding the question of affordability and competitiveness," the European Commission states in its 2019 report on energy prices and costs in Europe.

Despite an overall rise in energy prices, European companies' aggregated energy costs fell by eight percent between 2008 and 2015 because they used energy more efficiently. But companies beyond the EU are also lowering their energy bills by making efficiency gains. "Other countries’ industries are sometimes more efficient than those in Europe," the EU report says. "In fact, Japanese and Korean industry’s exposure to higher energy prices has made them more energy-efficient; energy producing countries (Russia, US) are less energy-efficient […] Thus, we see again that rising energy prices may in themselves spur the drive for reduced energy consumption and greater energy efficiency."

Germany's entire industry cut its energy use by more than a quarter between 1990 and 2013 alone, according to the economy ministry. Countless studies show that German industrial companies still have much scope to increase energy efficiency further – although this is becoming increasingly difficult especially for energy-intensive industries as they have picked most "low-hanging fruits" already.

Similar effects apply to household power prices in Germany. Even though power prices have risen sharply in recent years, households spend the same share of their disposable income on electricity as in the 1980s because incomes have risen, and because they use less power – less than a third than US households, for example.

Varying importance of power prices

Regardless of rising efficiency, commercial enterprises use about 74 percent of all power consumed in Germany, according to data from utility association BDEW. Industry alone consumes 47 percent of the electricity used in the country.

The range and impact of energy costs varies widely across different sectors of the economy. Whereas companies engaged in making electronics or cars only spend about one percent of their total expenses on energy, this share rises to an average 3-20 percent for energy-intensive companies making cement, paper, glass, steel and basic chemicals, according to EU data.

But for some companies and sectors, power prices are particularly crucial. For example, power makes up around 50 percent of total costs for producing aluminium, 13 percent for paper, and 10 percent for steel.

Producers of aluminium, basic chemicals, paper and steel are particularly sensitive to rising power prices, mainly because they use a lot of power to produce standardised goods that are traded internationally, according to an analysis conducted by think-tanks Ecofys and Fraunhofer ISI for Germany's economy ministry.

But the case of aluminium smelters also illustrates that large industrial consumers are not completely helpless in the face of shifting wholesale power prices. In effect, they can even benefit from price swings that have accompanied the roll-out of intermittent renewable power by ensuring that energy-intensive processes coincide with strong renewable generation, and thus lower prices. For example, Trimet Aluminium, which accounts for around one percent of Germany's entire electricity consumption, has created a large “virtual battery” by making highly energy-intensive electrolysis more flexible. Wholesale power prices even turn negative more often, allowing Trimet to earn money by drawing electricity from the grid when renewable power is plentiful.

Power prices and competitiveness

The Ecofys and Fraunhofer ISI study also notes that it is difficult to make general statements about the competitiveness of industry or even of different subsections.

"The analysis of competitiveness at the enterprise level reveals large differences between the enterprises in a sector. It shows that company-specific factors, such as the integration of production processes, product differentiation, diversification and management, play a major role and that even high electricity costs can be compensated to a certain extent by higher prices for premium products," the study concludes.

The Ecofys and Fraunhofer ISI experts stress that even for energy-intensive products, other costs – for example for labour and capital – are also decisive for competitiveness. They also highlight the importance of entirely different factors, such as proximity to clients or highly skilled employees.

International rankings consistently show that German industry remains highly competitive in a global comparison. For example, Germany came 7th in the World Economic Forum's latest global competitiveness ranking thanks to its strong performance "across the board," including the best innovation capability in the world, and it received top marks for infrastructure, macroeconomic stability, market size, health and a highly educated labour force.

German industry has warned repeatedly that high power prices could lead to an exodus of companies to cheaper production locations abroad. But so far, there is little to no empirical evidence that German companies have relocated production abroad to escape the effects of the country’s climate policies. Even the industry-sponsored German Economic Institute (IW Köln) states that industry exemptions from taxes and levies on the power price have meant that "no systematic exodus of energy-intensive companies has been observed."

To the contrary, industry's total share of Germany's economy has even risen slightly over the past 20 years. This is in sharp contrast to many other countries like France, Britain and the US, where industry's role has declined significantly over the same period.

Sweeping statements about power prices from industry groups also hide the fact that more than half of German businesses say they are in favour of more climate action measures, even if these are an additional burden, according to a survey conducted by the German Chambers of Commerce and Industry (DIHK).

Comparing international prices

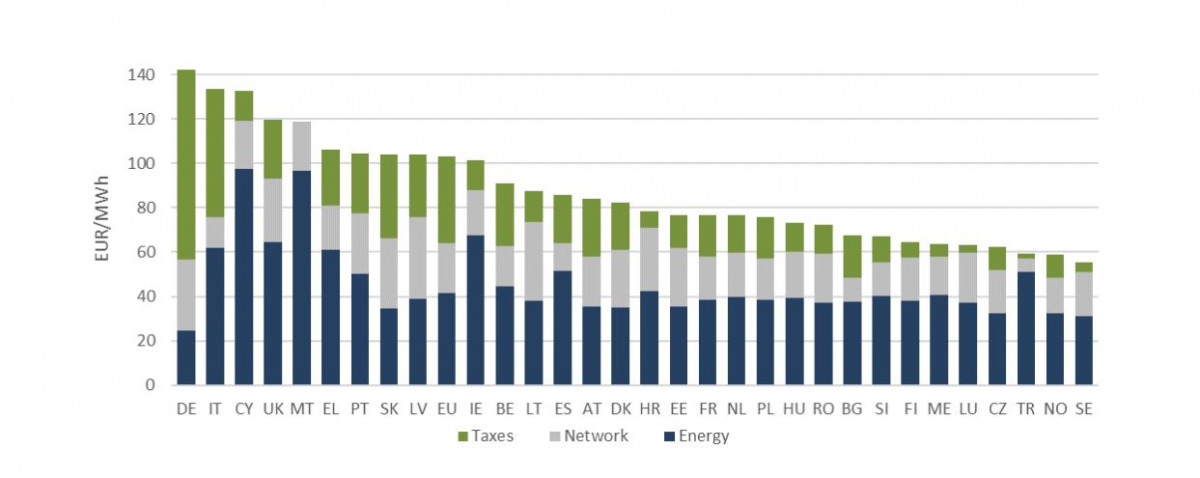

Given the wide range of prices industry pays for power in Germany, international comparisons are fiendishly difficult. Most comparisons underline the earlier finding that average German industry prices are high, while wholesale prices are relatively low.

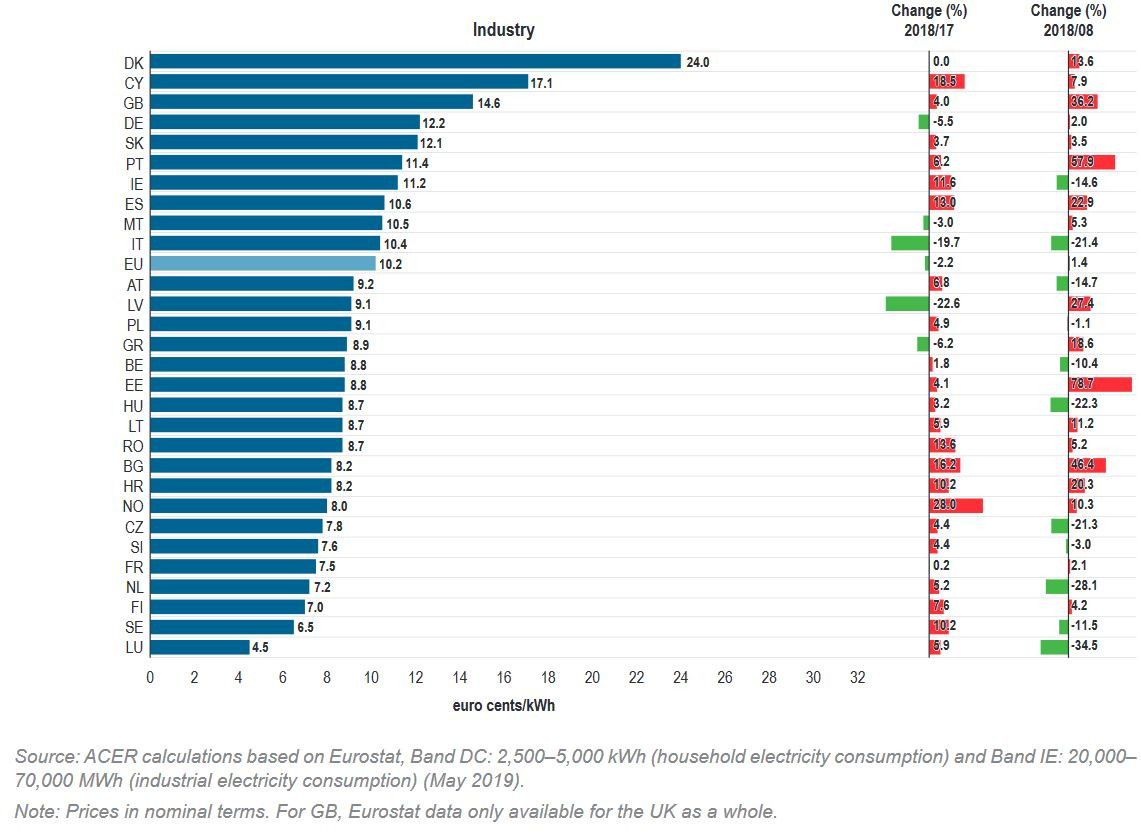

For example, Europe's Statistical Office Eurostat says the average power price for industrial consumers in Germany was about 14 cents/kWh in 2017 – the highest in Europe. But the following graph also reveals that German companies with maximum exemptions would pay the lowest price in Europe (energy price component):

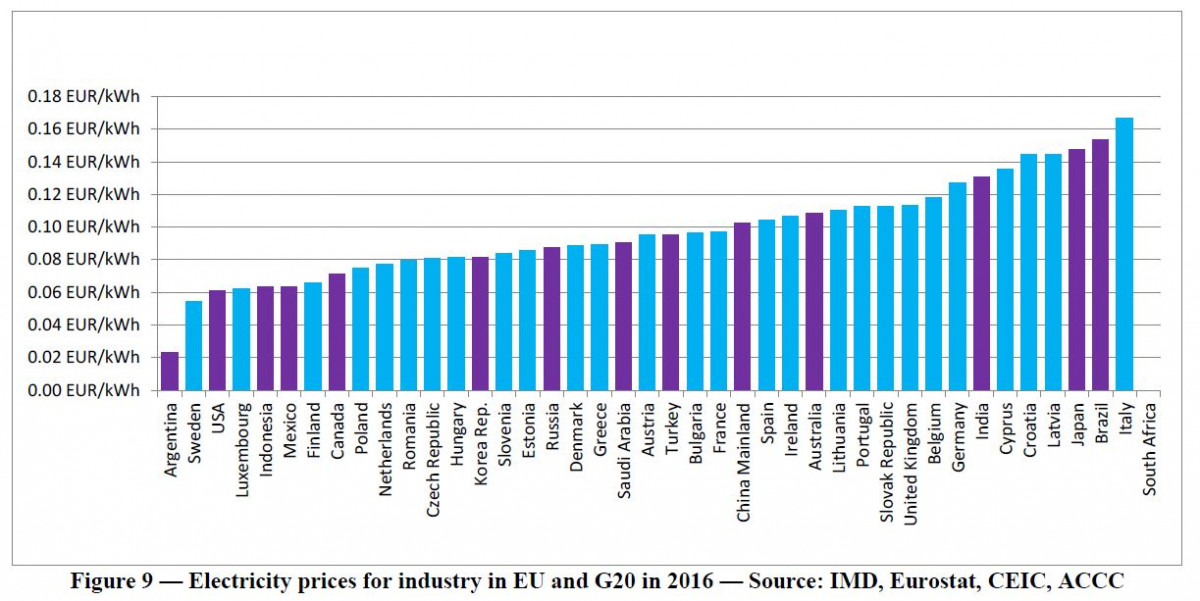

The graph below, culled from an EU study comparing prices in the EU with other G20 countries, shows that Germany no longer has the highest prices in the EU when different criteria are applied.

Another example for international comparisons is the following graph from the EU's Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER) 2019 report. It shows that industry power prices are considerably higher in Denmark, Cyprus and the United Kingdom than in Germany. Also note the different positions of Italy and Denmark compared to the above EU G20 graph.

Some illustrations also aim to capture the wide spread of German industry power prices in an international comparison. The following graph from an Ecofys/Fraunhofer ISI study comparing international industry power prices dates from 2015. It indicates Germany's power price range for large consumers enjoying exemptions of varying degrees with two bars (labelled DE and (DE)).

Finding a path through the "subsidy jungle"

The discrepancies between the graphs above again underline the importance of German taxes and levies, which is why they deserve a closer look.

In order to ensure their international competitiveness, most energy-intensive companies are eligible for partial or full exemption from levies like the renewable energy (EEG) surcharge, which finances the renewables roll-out. Other so-called privileges include exemptions from grid charges, the concession levy, a tax on the use of public space for power lines, electricity tax, and surcharges for combined heat and power (CHP) plants and offshore wind. The system is so complex that Green politician Oliver Krischer has called the German rebate system a “subsidy jungle.”

The renewable energy surcharge is the most prominent levy on power prices. It will total around 22.7 billion euros for all consumers in 2019, according to the utility association BDEW. Thereof, industry will pay almost six billion euros, compared to more than eight billion euros shouldered by households.

A breakdown reveals that a comparatively small number of companies is exempt from the full surcharge – but their power consumption is huge.

Out of 46,400 industrial companies active in Germany, 96 percent paid the full surcharge in 2017, while only four percent benefitted from exemptions, according to the association. At the same time, 41 percent of electricity used by industry is partially exempt from the surcharge, while 43 percent is not exempt at all. The remaining 16 percent of the power originates from own generation facilities, part of which is also exempt. The utilities forecast that German industry will use a total of 246 TWh in 2019.

In 2018, a total of 2,156 companies were exempt from paying the full renewable energy surcharge on a combined 110,500 GWh, according to data from the Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control (BAFA).

Industry exemptions from contributions to renewable energy expansion, grid modernisation and other levies are controversial in Germany. This is because they push up power prices for all other users, including smaller companies, which are forced to compensate for the shortfall. Preferential treatment of energy-intensive industries cost households and non-privileged companies up to eight billion euros in 2017. The exemptions were originally designed to ensure the international competitiveness of energy-intensive industries, but the Greens and other critics question why slaughterhouses and banks' data centres should also be among the beneficiaries.

Uncertain outlook for industry power prices

Given ongoing concerns about power prices and industry competitiveness, there are frequent calls for a fundamental overhaul of Germany's complicated system of financing the Energiewende mainly via the power price. Many critics argue that power will have to become much cheaper in order to incentivise the switch from coal, oil and gas to renewable power not only in industry but in all other economic sectors as well – a process often referred to as electrification or sector coupling.

Recent proposals by energy-intensive industry to lower CO2 emissions by using fuels based on hydrogen made with renewable power also illustrate that many projects require low power prices to become economically viable. Thus, the power price is a key element to determine the costs of avoiding emissions.

BASF climate and energy expert Bachmann notes that the complicated system creates investment insecurity even for privileged companies paying low power rates. "The problem is that you never know for sure whether you will qualify for exemptions five years down the line," Bachmann says.

Forecasts also differ on the future development of power prices for industrial consumers in Germany. Whereas industry associations said that Germany's coal exit will push up power prices considerably and called for compensation, the energy think-tank Agora Energiewende* said the phase-out and the continuing roll-out of renewables will have "very little" impact only on electricity prices in general, and that energy-intensive industry even stands to benefit.

Germany’s energy and economy minister Peter Altmaier begun his term with a promise to reduce the power price burden for small and medium-sized industrial companies, but industry representatives say they are frustrated because there has been no progress in this regard.

Many companies keep a keen eye on green power purchase agreements (PPA) in order to get a better handle on power prices. These contracts between a power generator and a consumer – for example, between a wind park and a factory – specify the terms for the sale of electricity, offering long-term price security.

*Like the Clean Energy Wire, Agora Energiewende is a project funded by Stiftung Mercator and the European Climate Foundation.