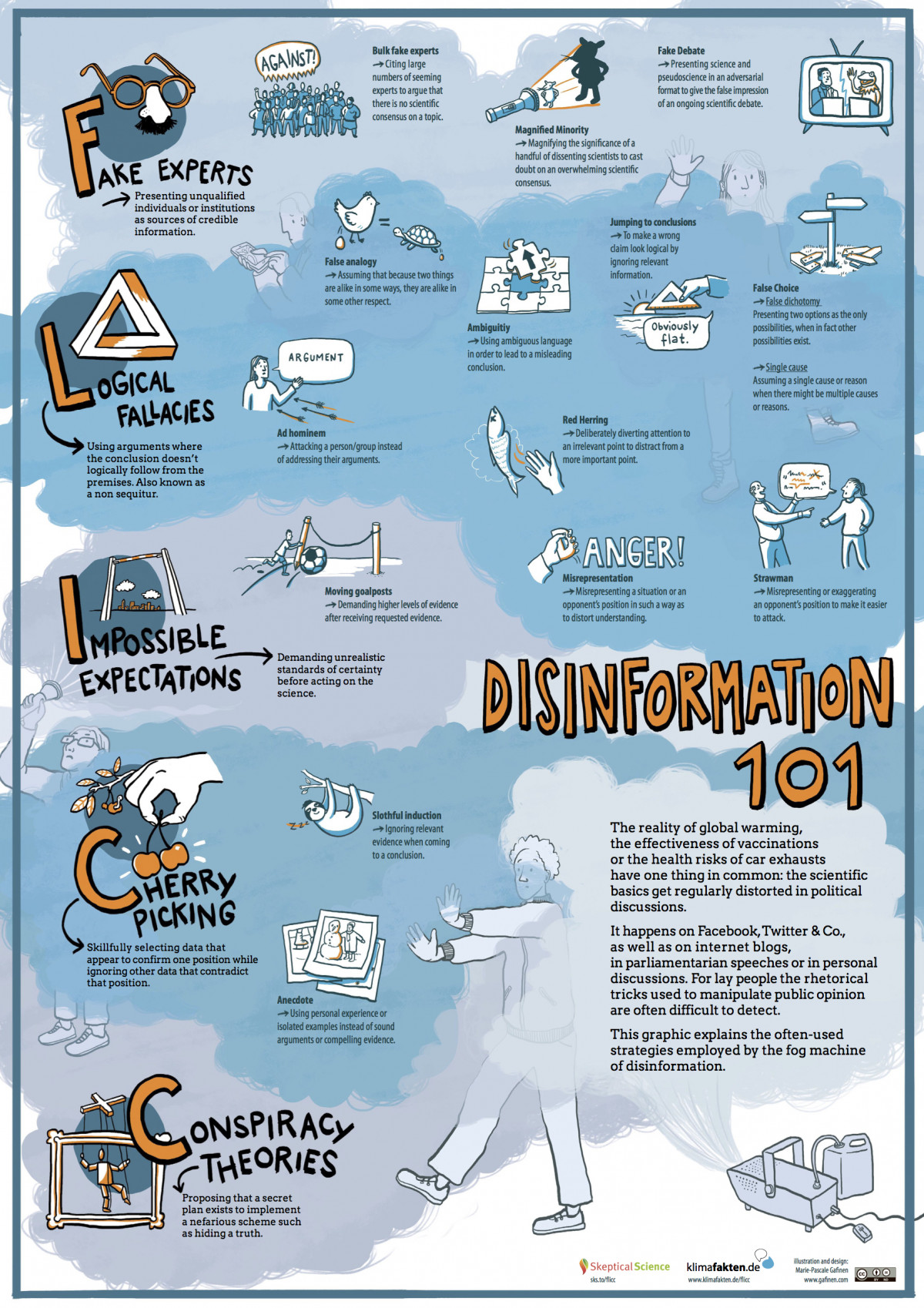

Watch out for F-L-I-C-C!

You can download the infographics here: in pdf format (approx. 1.3MB), in jpg format (approx. 1MB) and in png format (approx. 1MB).

One year ago, a retired pulmonary physician from a small town in North Rhine-Westphalia suddenly became prominent in the German media: The doctor, Dieter Köhler, earned his fame through a three-page statement, where he objected to the rationale behind driving bans for diesel cars in several German cities. In contradiction to established knowledge in scientific fields like pulmonology, toxicology or epidemiology he – and a number of co-signatories – argued against air quality standards in Germany and suggested that current EU-wide limits for nitrogen oxides and fine particulate matter were unnecessarily strict.

What started as an opinionated intervention by a few self-declared experts quickly turned into a case study for one of the techniques frequently used to seed doubts about politically inconvenient science. It also became a prime example for at first sloppy, and then later responsible, fact-based, journalism. Köhler’s petition came in the middle of a heated political debate – with public health experts, environmentalist NGOs and Green politicians on one side, and car manufacturers, industry lobbyists and some conservative politicians on the other. Opponents of the driving bans quickly picked up the ball. Several media outlets gave Köhler a stage, letting him present his views without checking the factual basis. Politicians at the highest levels – for example the federal minister for transportation, Andreas Scheuer (CSU, the Bavarian sister party of Angela Merkel’s CDU) – used Köhler’s petition to call into question long-established limits for air pollutants. Several days passed before other – credible – scientific voices appeared in the media debunking his claims, and before several journalists published detailed fact-checks, laying bare basic mistakes in Köhler’s argument and showing it to be false. It became clear that he had left out relevant information and misrepresented scientific findings.

The incident was a lesson in the dynamics of public debates – and the methods of disinformation. The doctor’s statement was a textbook case: If you want to make an un-scientific claim sound credible, you cherry-pick convenient pieces of evidence (and ignore information that contradicts your position). If you want to seed doubt on scientific facts, present a supposed expert (aka “fake expert”) who dissents, and rely on media that is known to feed on controversy and increasingly lacks specialised staff to quickly dive into the credibility of scientific – or unscientific - arguments or vet their proponents.

Psychologists and communications scholars have studied the strategies of disinformation campaigns extensively. They identified a number of core methods used again and again by science deniers (or “skeptics” as they often brand themselves to appear more favourable) –whether they attack the science behind climate change, vaccinations or clean air regulation. The five most important tactics are featured in a new infographic, recently published by klimafakten.de, CLEW’s German-language sister project. It explains the general methods, tabulated with their initials

F-L-I-C-C:

- Fake experts,

- Logical fallacies,

- Impossible expectations,

- Cherry picking and

- Conspiracy theories

These core tactics are then differentiated into sub-categories and explained further.

The infographic was developed together with the international team of skepticalscience.com, the award-winning website debunking false claims on climate science, and Hamburg-based illustrator Marie-Pascale Gafinen. It is available online in English and German (where the acronym of the core tactics is P-L-U-R-V). More versions of the acronym may become available in different languages as well. In addition to the electronic version, the graphic can be ordered as a printed poster in A2 format via Klimafakten.de (while stocks last).

Since every journalist should be aware of the strategies of those who spread disinformation, the poster (or a print-out of the pdf) would be a great addition to any editorial office.