Franco-German push for EU green industrial revival needs close alignment to succeed

*** Please note: this factsheet is part of a CLEW cross-border cooperation, exploring the Franco-German approaches to climate and energy and how these affect the vision of the EU’s energy future. You can find the full dossier here.***

The sizeable rewards of economic cooperation are part and parcel of the European Union’s success – and internal debates about how to implement it best have provided the bloc with a reliable background noise since its foundation. Germany and France have been among the greatest advocates for greater interconnection between EU members’ industrial policies. Yet, they often have been equally determined to assert their own national approaches outside of Europe-wide policy. With international climate targets requiring businesses to clear ever-higher sustainability hurdles, pressure is mounting on Europe to bolster its economy against competition in key green industries, such as clean hydrogen, batteries and renewable power installation.

The proliferation of sustainable technologies has been enabled by both falling prices, and targeted support from powerful nations, most notably the U.S. and China. Maintaining industrial leadership in these areas has been made significantly more challenging for the EU through Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the effects this has had on the bloc’s security, energy supply and economic stability.

“Electric shock” of the energy crisis upset tried industry policies

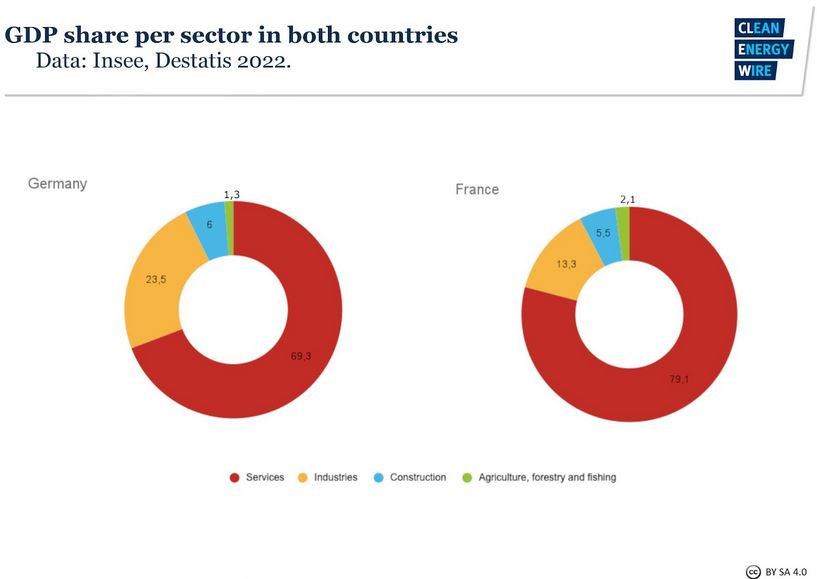

Disputes between France and Germany during the 2022 energy crisis have repeatedly been seen as obstacles to finding a unified position. At the same time, Paris and Berlin have spearheaded efforts to formulate an EU response to the U.S. government’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). This is coupled with efforts to develop European support mechanisms in response to the coronavirus pandemic and the energy crisis, with a view to forming a coherent, forward-looking framework for sustainable, industrial transformation within the European Green Deal Industrial Plan. Despite the differences between their energy systems and industrial structure, the EU’s two major economic powers are compelled to bridge their industrial policy gaps, says Philipp Jäger, economist at the Jacques Delors think tank in Berlin. “While Germany is looking to retain and transform the large industrial base it still has, France is hoping to regain lost production capacity in the shift to decarbonisation,” he added. Both therefore have a strong interest in quickly scaling up key transformation industries, Jäger said.

Amid the upheaval caused by the pandemic and the energy crisis, a tendency towards more state intervention has gained traction in Europe, much like in China, India or the U.S.. In Europe, such an approach had been hampered by Germany’s rejection of EU industry aid schemes until recently, he argued. “There’s great relief in France that the German government has moved from its position and is ready to get more involved in market developments.” The current momentum amassed for joint large-scale industry projects could permanently elevate energy and industry cooperation to a new and more integrated level, as most policymakers agree that a greater interlinking of infrastructure makes sense from an economic and supply security perspective. “And that this is in the national interest,” Jäger added.

For Maxence Cordiez, researcher for European policies at the French government’s Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA), the crisis has acted as “an electric shock” for Europe. It greatly accelerated joint efforts to encourage manufacturing of strategic equipment needed for a green transition through fast-tracked procedures and additional state aid outlined in the Net-Zero Industry Act. Until the pandemic and the war on Ukraine, the EU had “an extremely liberal vision” in which protectionist tendencies carried little weight. This has been a mistake, Cordiez argued: “New technologies, like in the early days of solar panels or battery manufacturing, are not often profitable in the beginning.” With regards to solar panel production, for example, this has already led to a loss of significant industrial capacity to China, which developed domestic solar PV in a protected market, scaled up production and then “attacked the European market.” As a result, Europe now faces a dependency on foreign supply for solar panels as it does in technologies where it did not previously lead, such as batteries.

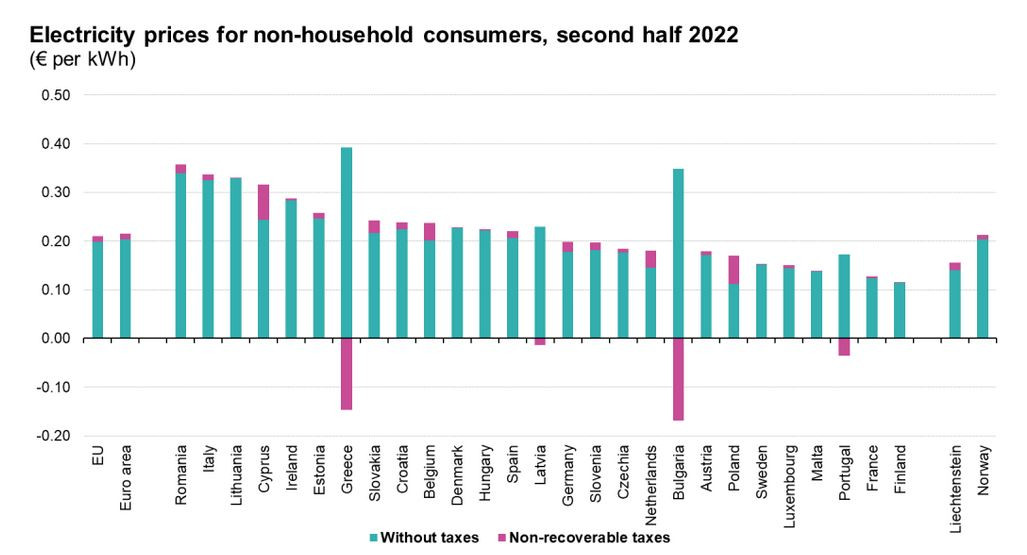

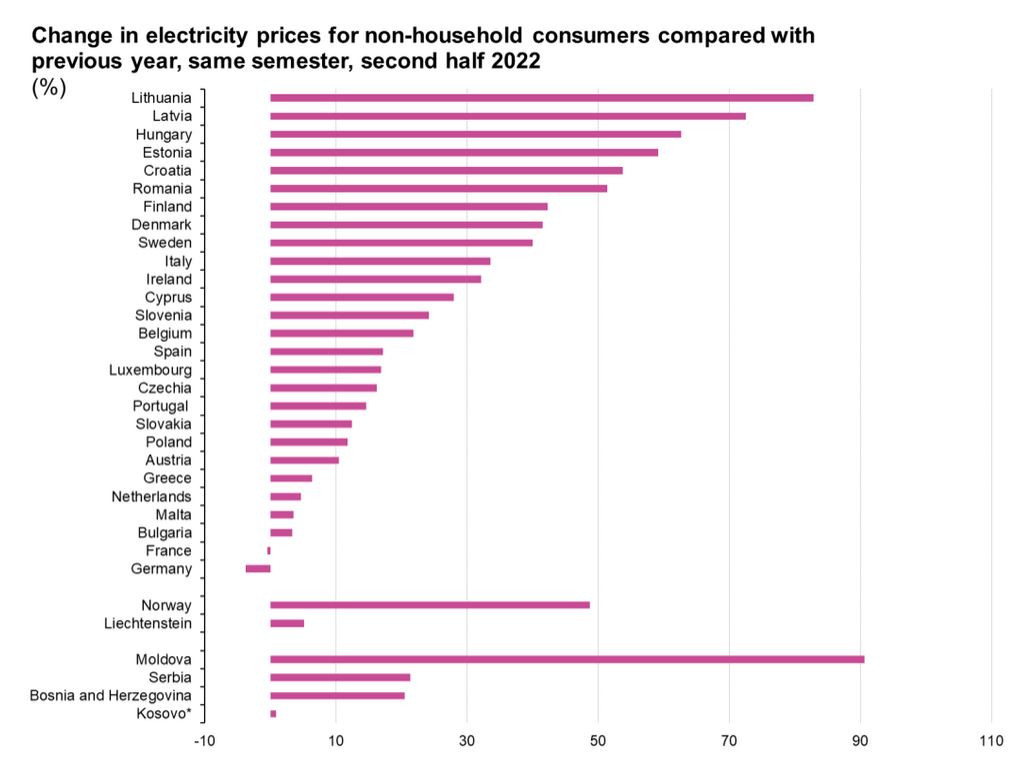

Europe must avoid beggar-thy-neighbour scenario for renewables

The difficulties faced by companies in future-growth industries, such as solar panel manufacturers, are often pinned to various regulatory changes that have come in support of climate action in recent years, both at the EU level and in national policy. Changes to subsidy programmes, for example the switch to auctioning renewable power, unclear renewables expansion targets, tightened emissions limits, have all posed challenges for companies’ planning security in both countries. Combined with different regulatory frameworks in place across Europe, this is compounding existing challenges to recruit enough skilled workers, prepare infrastructure and stock the necessary hardware and raw materials. “We need to collaborate closely in Europe to ensure a level playing field for our companies,” said Joachim Hein of the Federation of German Industries (BDI). Economic support policies, such as Germany’s initiative to lower energy prices for industry with subsidies if they promise to decarbonise and to remain in the country, should be implemented in concert by national governments to avoid beggar-thy-neighbour policies “or ideally come directly from the EU,” Hein argued. Industrial electricity prices, which are decisive for industrial competitiveness, differ quite widely across different European states, he warned. “If Europe wants to maintain its industrial strength and to stop companies from relocating overseas, EU-wide answers are needed on how affordable and competitive electricity prices can be ensured across the region.”

One example of where a more coherent push could prevent inefficient outcomes is the auctions system for renewable power installations, according to the Franco-German Office for the Energy Transition. As auctions always ensure prices are the determining factor for deciding on locations, investors will seek to put up wind turbines and solar panels in regions with the highest average returns. This comes at the expense of systemic support achieved through more scattered installations, which may not always operate most profitably but balance out weather-related energy production fluctuations. Coordinating support mechanisms, infrastructure planning and state guarantees could help ensure that investments favour supply security and decarbonisation over profits. Otherwise, geographical conditions within the EU ultimately could determine each country’s power price.

Jean-Baptiste Leger from the BDI’s French counterpart, the Movementof the Enterprises of France (Medef), shared the view that European industry needs assurances and a clear course forward. “Between 2023 and 2030, we really need to bend the curve of our greenhouse gas emissions, which is an extremely short period of time for investment projects,” Leger said. “And everyone is in favour of decarbonisation – but not at any cost.” France and Europe had no other choice than to bet on resolute re-industrialisation policies to retain their sovereignty in a time of green transformation, the industry lobbyist said. “Ultimately, this re-industrialisation must enable a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, due to the simple fact that we are repatriating some of the emissions we offshored between the 1980s to 2020s.” Large-scale relocation of production facilities outside of Europe, very often to China, allowed the region to reduce its industrial emissions in the past. Bringing production capacity back to the EU therefore must “reconcile carbon neutrality with employment and meet our environmental and social standards,” Leger added. Regulatory instability and inconsistencies among member states would directly undermine this aim.

The challenges Europe is facing in this scramble for industrial leadership already become visible in the electric vehicles sector, which has seemed to place U.S.-American and Chinese manufacturers squarely ahead of their hitherto more successful European competitors. “The traditional car industries both of France and of Germany must adapt to this future,” said Andreas Rade, executive of the lobby group German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA). “This is about a complete transformation of one of Germany’s most important industries – and it should remain one of the most important industries also after the transformation,” Rade said. Electrification and digitalisation are about to “turn the whole industry around,” which would require European brands to change course fast while at the same time making sure that the structures, they developed in the preceding decades are not left behind. “Re-inventing a functioning model comes with more baggage than introducing a new one,” he cautioned.

‘Open strategic autonomy’ to replace French dirigiste and German ordoliberal industry concepts

How successful Europe’s industry will be in reinventing itself hinges on the quality of coordination and compromises between Berlin and Paris. Opposing economic policy principles on either side of the Rhine River, the heavily industrialised border region between the EU’s two largest states, have shaped the fate of European industry since the early days of integration in the post-war period, often described as a competition between ‘French dirigism’ and ‘German ordoliberalism.’ In arguments about resource pooling, state intervention and regulation, both countries projected their preferred approach on the European stage and set the course for the bloc as it evolved into the modern-day EU. Initially, the focus rested on the coordinated creation of national industrial champions, including brands like Renault or Volkswagen, EU think tank Bruegel noted.

It then shifted to a phase of stronger multilateral efforts that saw the removal of more internal trade barriers, and the formation of European aviation heavyweight Airbus, an icon of joint European industrial policy. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, comprehensive market liberalisation within the EU and the outsourcing and privatisation of production capacity and infrastructure prevailed until the global financial and subsequent European debt crisis of the 2010s. Following the shakeup of the financial system, the goal of reindustrialisation in line with climate targets started to emerge as a European consensus. Against the backdrop of rising geopolitical tensions, this led to the European Green Deal in 2020 – followed immediately by the pandemic and then the war in Ukraine. The chain of disruptive events gave rise to the concept of ‘open strategic autonomy’ formulated by the EU Commission in 2021, which, at its core, deals with the risk of supply disruption for critical items. This includes efforts to ‘de-risk’ by developing domestic capacities in strategic industries and reducing supply dependencies, Bruegel said in a 2023 analysis of “Europe’s new industrial revolution.

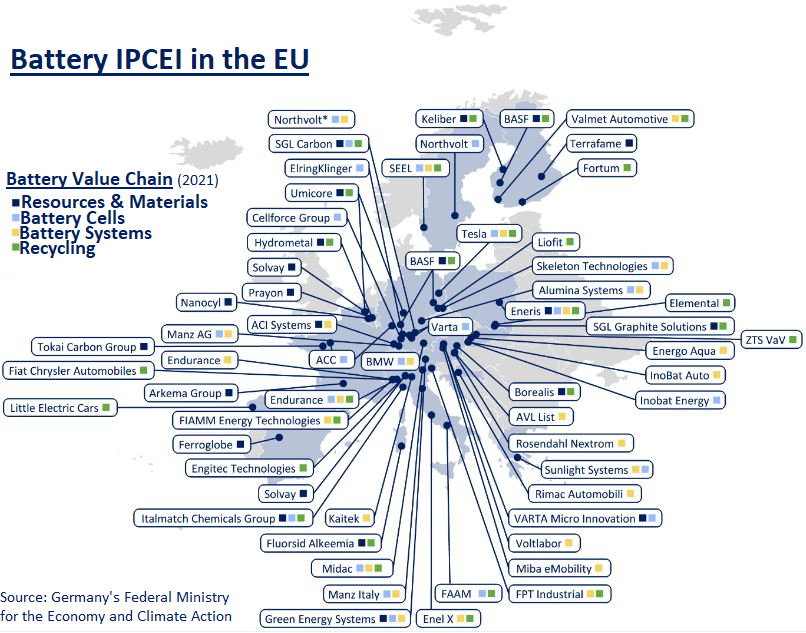

Confident in their pivotal role in moving the bloc forward once again, the joint declaration for a “renewed impetus in European industrial policy” tabled by France and Germany in late 2022 promised the creation of a “European platform of transformation technologies” to boost European strategic autonomy and access to raw materials in fields like renewable power installations, hydrogen production and batteries. Key instruments in this effort would be the Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI) industry support scheme and the introduction of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) that ensures non-EU manufacturers “match our strong climate change commitments,” economy ministers Bruno Le Maire from France and Robert Habeck from Germany declared.

While the modified IPCEI scheme has been hailed by industry groups and governments in Berlin and Paris as the ideal vehicle for industrial progress across the EU, observers like economist Philipp Jäger warn it could cement France's and Germany’s industrial dominance in the EU. “Differences between the two are much smaller than compared to other, smaller and less wealthy member states, which lack the same administrative capacities and money to fully utilise the potential of support programmes,” he argued. France and Germany both want to relax state aid rules at EU level to support their industries more comprehensively. “But they will have to make concessions to other member states to get what they want,” Jäger said. Any rulebook allowing richer member states to shore up their industry in the transformation should thus be combined with funding programmes to avoid economic divergence between EU member states, he added.

“Local production” and “necessary imports” complicate self-styled hydrogen leaders’ aims

With hydrogen production, one of the most forcefully pursued IPCEIs, both France and Germany hope to kickstart further development in a field their industry is already heavily invested in. Some 430 billion euros have been earmarked by 2030 EU-wide for national synthetic fuel hydrogen strategies. Ministries in Berlin and Paris regard hydrogen as a prerequisite for substituting fossil imports, as leaders French president Emmanuel Macron and German chancellor Olaf Scholz both outlined in early 2023. The government leaders promised to build “a resilient European hydrogen market based on the strength of local production and the sustainability of necessary imports.” However, despite the high-level endorsements, differences about the details of “local production” and the scope of “necessary imports” persist among the self-styled leaders on hydrogen. Macron repeatedly stressed the EU’s need to be “vigilant” of replacing import dependencies on fossil fuels with renewables-based green hydrogen imports, an option strongly pushed by Germany. Europe could cover a large share of its hydrogen demand itself because “we have both renewable energies and nuclear power,” the French president said in late 2022, calling for a “European ambition” to integrate nuclear-based ‘pink hydrogen’ in long-term EU plans. Germany’s National Hydrogen Strategy, updated in mid-2023, makes no mention of nuclear power – and French efforts at the EU level to integrate nuclear power in hydrogen plans has proven an arduous task despite common targets. Eventually, nuclear power was recognised as ‘neither green nor fossil fuel’ but ‘low carbon,’ in the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive (RED).

Industry groups BDI and Medef have been careful to avoid a dispute over the ‘colour’ of hydrogen that routinely dominates debates at the political level, rather pointing to the need to resolve differences regarding the CBAM scheme and electricity market design. On hydrogen, each country could do its own industrial deployment, while pooling resources to accelerate learning processes in infant industries. Medef’s Jean-Baptiste Leger said it is necessary to “move forward with as much pragmatism as possible, with enthusiasm,” while the BDI’s Joachim Hein called the debate "not helpful at this point.” The focus should be on “making [hydrogen] available in large quantities in the foreseeable future.” Irrespective of the colour debate, both countries are already working on cross-border hydrogen pipeline projects, he added.

French industry umbrella group France Industrie together with the BDI in late December 2022 signed a joint declaration on decarbonisation, calling on the EU framework to recognise the role of low-carbon hydrogen climate action. In effect, this was calling for acknowledgement of low-carbon hydrogen derived from nuclear energy, Simon Pujau of French hydrogen industry group France Hydrogene said. "This will be indispensable if industry is to meet its climate targets,” he insisted. The high load factor France can operate its electrolyser fleet with would be “the major competitive advantage of the French industry,” Pujua argued. “The French model is not based solely on renewable hydrogen but also on electrolysers connected to the French electricity grid, which is already largely carbon-free.” Besides that, the costs associated with Germany’s green hydrogen import plans have to be taken into account, researcher Maxence Cordiez said. “Hydrogen will be very limited in terms of volume available for a long time, so it must not be wasted.” Apart from substantial conversion losses for shipped hydrogen, transporting and storing the gas at ultra-low temperature is very complicated, he added. “There are leaks, it is very expensive.”

“France does not believe in the German model of hydrogen based on renewables production imported from Saudi Arabia or Chile. Germany does not believe at all in the French model of hydrogen based on nuclear power,” stated Pascal Canfin French MEP for liberal Renew Europe in an online panel on Franco-German nuclear positions. “It doesn't matter. May the best man win! When you look at the amount of electricity that needs to be produced in order to reach our climate objectives in industry or in transport, for example, it is so massive that we need all the solutions,” he said.

Observers such as Olivier Appert, advisor to the French Institute for International Relations (IFRI) and former board member of state-owned French energy company EDF, are wary of unresolved tensions in the debate. “When energy mix choices and energy policy choices are difficult to reconcile, it's not easy to find areas for cooperation,” he sadi. For any large-scale industrial policy in Europe, the question whose factories will contribute what are soon to occupy the limelight. Unlike the goal of creating an aviation champion with Airbus, a lack of willingness to cooperate on nuclear power for hydrogen production, which could greatly reduce the French nuclear power bill, is making breakthroughs more difficult on the German side, he argued. “It's a pity, because there have been a number of successes in industrial cooperation,” Appert said, pointing to the bilateral joint venture between EDF and engineering company Siemens that spurred innovation in nuclear power in the form of the co-designed European Pressurised Reactor (EPR). This venture, however, was followed little success in aligning the two countries’ stance on the technology. Siemens had been part of the French nuclear industry’s flagship Flamanville project until its withdrawal from the industry in 2011.

Renewables slow to gain traction in common European projects

However, at the same time Siemens did build out its presence elsewhere in the French energy sector and France so far has bought about two thirds of its offshore wind turbines from Germany. And German firms invested not only in the French renewables market but some of them also depend on French renewable production. German-Spanish joint venture Siemens Gamesa provides turbines for half a dozen offshore projects off the French Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts. Turbines are built in a factory in Le Havre, which started manufacturing in 2022. “The production of the French wind farms goes to foreign subsidiaries, half of them to German companies,” said Herve Machenaud, director of think tank Cereme and former executive director of EDF.

Scepticism towards the hydrogen push also comes from the German renewables industry. “IPCEIs generally are a useful scheme to boost projects in key areas,” said the German Renewable Energy Federation’s (BEE) EU policy expert Reiner Hinrichs-Rahlwes. However, “cooperation on hydrogen production bears the risk of simply serving as a ‘greenwashing’ vehicle for nuclear power,” he argued. “I’m therefore not sure if this is the best area to improve cooperation between the two countries.” In contrast, “solar PV manufacturing would be an area where cooperation makes a lot of sense,” the renewable power industry lobbyist said. Germany “currently probably has an edge in the installation of solar PV and in manufacturing wind turbines. I don’t see strong efforts in France to significantly change that,” he added.

While an IPCEI for solar power production was launched in 2022, it has come rather late in comparison to IPCEIs for other technologies. This is despite the jointly stated intention to repatriate production capacity in the context of the tremendous growth rates expected in the industry in the near future. Industry group Solar Power Europe said deployment in the EU could double between 2022 and 2026 to 484 gigawatts. In France, two thirds of all public support payments for reneweables, totalling about45 billion euros, are likely to be repaid within the period 2022 to 2023 alone, the French Renewable Energy Syndicate (SER) said. “The result of public support is that these technologies are now hyper-competitive,” said SER’s Alexandre Roesch. In offshore wind power, this already had created a robust network that now must only be kept running. For the solar PV value chain, on the other hand, France must seek a revival as much as Germany. “Our ambition in France is to set up a solar PV gigafactory again, and so is the Germans’,” Roesch said.

In a 2023 analysis, French international relations institute IFRI acknowledged the value of Germany’s vigorous renewable power push, with a notable focus on using new renewable installation capacity to develop economically disadvantaged regions, where many of Germany’s IPCEI activities on hydrogen take place. At the same time, it backed the view that vigorous action is needed to avoid Europe’s wind power industry mimicking the fate of solar PV production and moving to China. The Asian country already supplies some 80 percent of the components that are then manufactured into turbines in Europe.

Car sector wary of creating new champions in mature automotive industry

Beyond hydrogen, rolling out battery production is another area both countries are aiming to boost quickly. Batteries figure large in future IPCEI planning and France and Germany launched cross-border battery cell consortium already in 2019. Yet, the ambitious plans for battery manufacturing could not replace better coordination in other areas to make the electric car industry flourish in Europe, car lobbyist Andreas Rade said. Trying to create a new joint industrial heavyweight “is certainly not the best way forward for a mature industry,” he said. Instead, setting common standards for infrastructure and payment methods helps to reduce uncertainty both for the industry and customers, which are currently lacking. “Inconsistencies are especially problematic in the freight sector,” he added. Profitability and seamless operation of duty vehciles are even more essential for businesses to adopt non-fossil technologies than for private passenger car owners.

“Even if clean transport vehicles are already available, no one is going to buy these if the framework conditions are inadequate,” Rade said, adding that more grid connections, charging infrastructure and “as much renewable energy as possible” are needed to master the shift. Even if charging networks in France and Germany already are among the most developed in Europe, coordinated efforts are only taking shape slowly, he added. The joint EU charging directive, agreed in spring 2023, followed only after vehicle fleet emissions standards were tightened, a skewed order that complicates harmonised adoption. At the same time, technical implementation, provision of raw materials or energy supply all are examples where joint strategies are lacking in the transport sector. “What is missing is a general understanding of the complexity of this transformation.”