How energy systems and policies of Germany and France compare

Contents

- Geography, Politics, Economy: Different Landscapes Along the Rhine River

- How Energy Systems Compare: Primary Energy & Electricity Production

- Energy Consumption Declines in Both Countries

- Renewables set to grow fast across Europe

- Heating

- Electric mobility

- Energy storage

- Power grid

- Nuclear power: Phase-Out for Germany, Renaissance for France

- Fossil fuels: Germany Leads Consumption with Gas as Key Driver

Germany and France are the two largest economies in the European Union and both play a key role in the bloc’s goal to become greenhouse gas neutral by 2050. France also aims to achieve net zero emissions in that year, while Germany plans to reach the target five years earlier, in 2045. Whether or not these ambitious goals can be met will for the most part rely on their governments’ policy decisions in various sectors, especially the most energy-intensive, and subsequently on their swift implementation. But with roughly 25 years left to radically change their energy systems, meeting those targets also depends on the current reality in energy policy prevailing in each country.

Highlighting the two countries' structural similarities and discrepancies allows a better understanding of where both of them stand as of 2023 and where they are headed given current trends. A caveat is that an entirely accurate comparison of available datasets is not always feasible between the two countries. This is due to the intrinsic complexities of counting emissions, investments and other developments in climate and energy policy, as well as the countries using different definitions, framings and accounting procedures to quantify their efforts. However, comparing available data can still offer an overview of the state of affairs in each country, where this can lead to contradictions, but also where synergies exist in the two approaches.

Quick facts

(Sources: Worldbank, Insee, IMF, Destatis, EU Commission, EEA, EU Parliament, BDEW, RTE, Energy Renewable Capacity Statistics; figures for 2022 unless stated otherwise )

|

FRANCE |

GERMANY |

|

|

Area |

544,000 km2 |

358,000 km2 |

|

Population |

66 million |

83 million |

|

GDP estimate 2023 |

2.9 trillion dollars (44,000 dollars/capita) |

4.3 trillion dollars (51,000 dollars/capita) |

|

Industry share of GDP |

13.3% |

23.5% |

|

Greenhouse gas emissions 2021 |

302.33 megatonnes (4.5 tonnes/capita) |

665.88 megatonnes (8.0 tonnes/capita) |

|

Emissions reduction 1990-2021 |

-24% (ca. -124,420,000 kt CO2eq) |

-41% (ca. -522,843,000 kt CO2eq) |

|

Emissions reduction targets |

-40% by 2030 (-50% proposed in 2023), net-zero by 2050 |

-65% by 2030, -88% by 2040, net-zero by 2045 |

|

Share of renewables in power production in |

27 % |

44% |

|

Share of renewables in primary energy consumption |

14% |

17% |

|

Share of renewables in final gross energy consumption |

20,7% |

20,4% |

|

Installed renewable power capacity |

65 GW |

150 GW |

|

Installed nuclear capacity |

61 GW |

4 GW (decommissoned in April 2023) |

|

Installed coal capacity |

2 GW |

37 GW |

|

Installed gas capacity |

13 GW |

31 GW |

Geography, Politics, Economy: Different Landscapes Along the Rhine River

Situated on either side of western Europe’s central waterway the Rhine River, France and Germany constitute the European Union’s core region - not only geographically and historically, but also in terms of population, economic size and diplomatic weight. The two EU founding members share a wide range of cultural, institutional and political characteristics, and superficially may look quite alike on many accounts. However, they often are further apart on policy issues than their similarities suggest, in particular regarding organisational practices and ideological approaches.

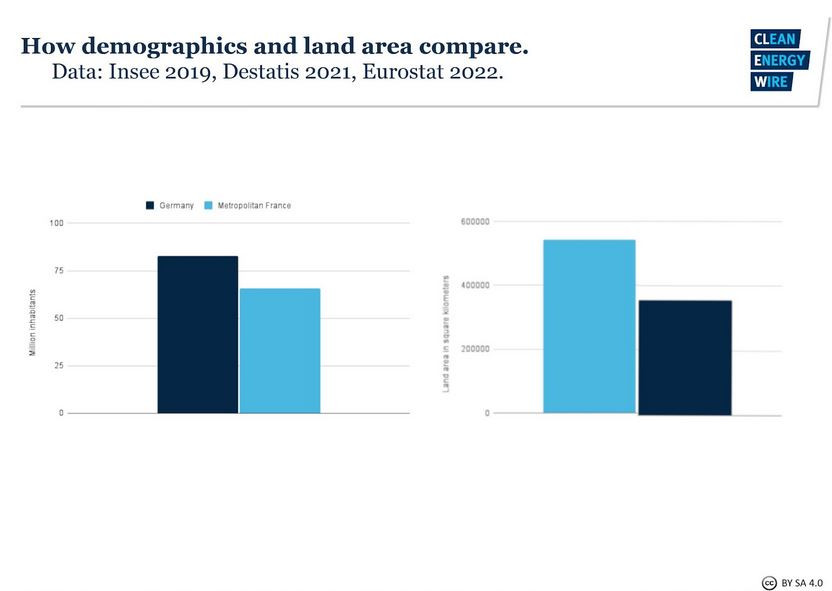

France is the EU’s largest state by area. Its European territory (metropolitan France) covers some 544.000 km2. By contrast, Germany’s area is roughly 358.000 km2, only about two thirds the size of its neighbour. In terms of population, the picture is reversed: with about 83 million people registered in the country, Germany is the EU’s most populous member state. France comes second, with nearly 66 million inhabitants. Consequently, Germany has almost twice its population density.

France is a highly centralised state with the capital Paris as its unrivaled economic, cultural and political centre. Consequently, the French president is endowed with a high degree of direct decisional power that is compounded by the fact that coalition governments are uncommon in France. Germany, on the other hand, has a strong federal political structure for its 16 states. Several cultural and economic centres are scattered across the country and state governments enjoy relative autonomy vis-à-vis with the federal government Berlin. Moreover, coalition governments have been the norm for decades, meaning the German chancellor regularly has to rely on negotiating compromises before taking a decision.

Germany boasts the EU’s largest gross domestic product (GDP) ahead of France by a considerable margin - it is estimated at some 4.3 trillion dollars against 2.9 trillion dollars for its western neighbour (IMF, 2023). For income per capita, Germany leads France with about 51,000 to 44,000 dollars per year. Together, the two countries account for about one third of the EU population and for more than 42 percent of the bloc’s total GDP.

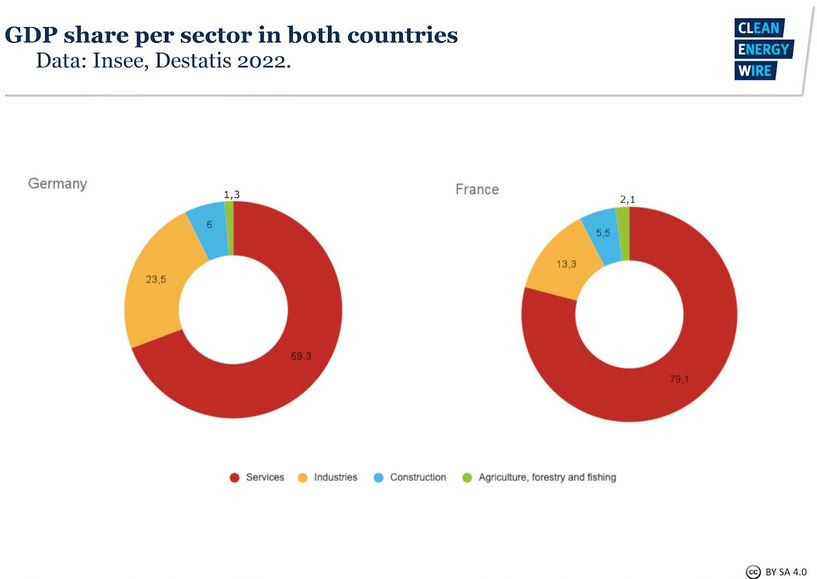

Regarding economic composition, the share of industry is much higher in Germany than it is in France: 23.5 percent (2021) and 13 percent (2022), respectively. This difference in part results from how both the countries navigated the fallout of the 2008 financial crisis, as well as the ensuing sovereign debt and Euro crisis, culminating in 2012. While French industrial production took a deep hit and remained significantly lower throughout the following decade, Germany’s economy emerged strengthened from the crisis not least thanks to its strong export-driven industrial sector.

France had some 259,300 companies in the industry sector in 2020, with 1,1 trillion euros of total revenue. The sector employed more than 3 million people in 2021. In Germany, the around 217,100 industrial companies registered as of 2021 generated a turnover of about 2.1 trillion euros and employed roughly 7 million people.

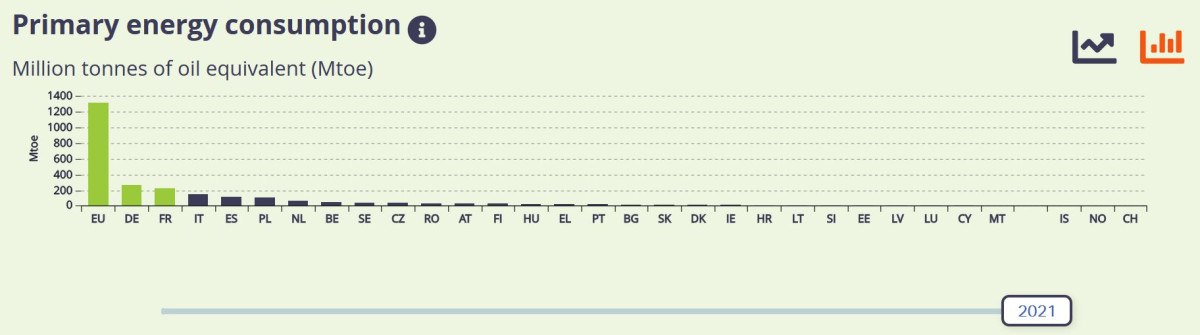

How Energy Systems Compare

Together, the two countries accounted for roughly 38 percent of total EU energy consumption in 2021. Of the roughly 1,300 million tons of oil equivalent used in the EU in 2021, Germany consumed 267 million tons and France some 224 million tons.

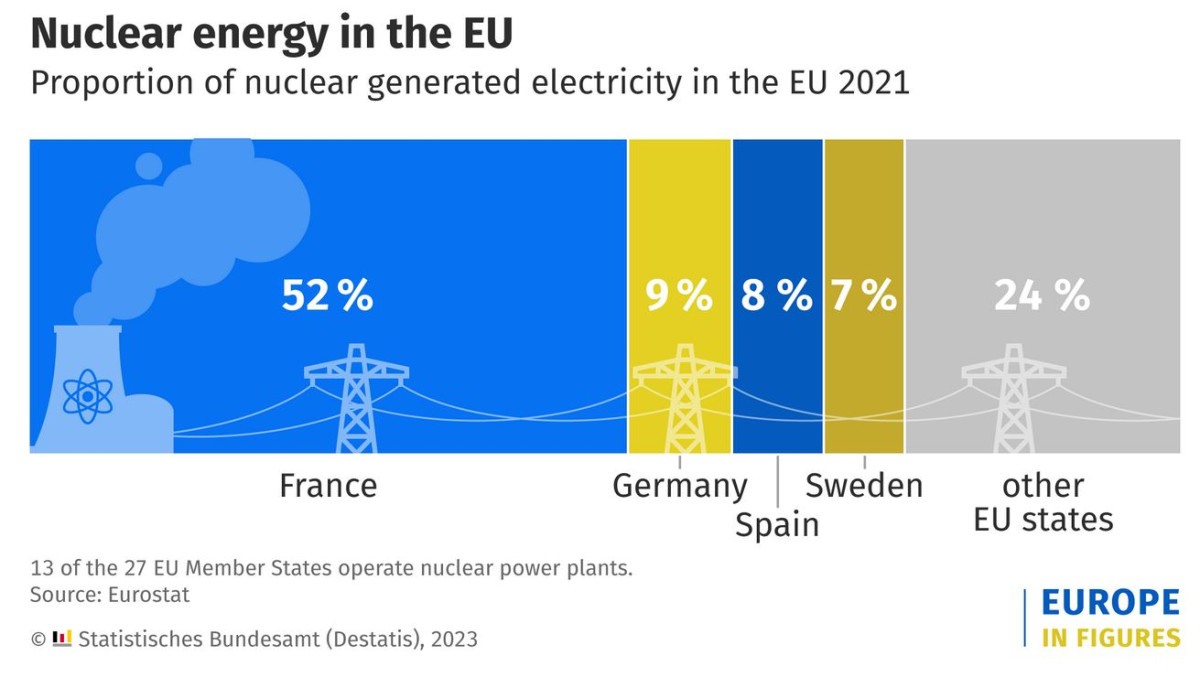

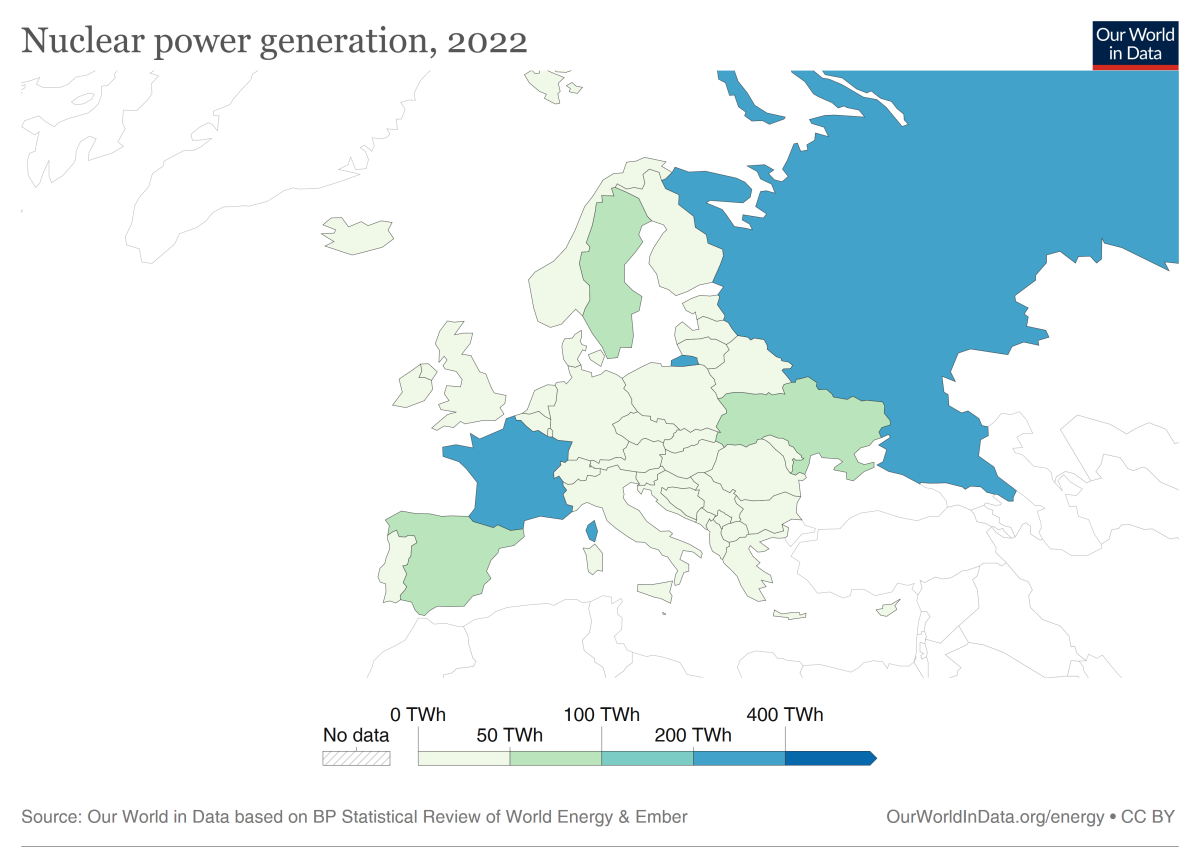

Apart from a heavy reliance on oil, the countries boast two rather different usage patterns with other energy carriers, especially regarding nuclear and coal power. Germany was the biggest coal producer in Europe in 2022 and accounted for 45 percent of its brown coal (lignite) and 25 percent of hard coal use. France, on the other hand, is by far the largest nuclear power producer in the bloc and accounted for 52 percent of total production in 2021.

Conversely, Germany opted to phase out nuclear power already in the year 2000 and completed its 'nuclear exit' in April 2023, after a short delay caused by the energy crisis. In France, coal-fired power generation also has been reduced greatly in the past decades and as of 2023, only four plants were in operation in the country.

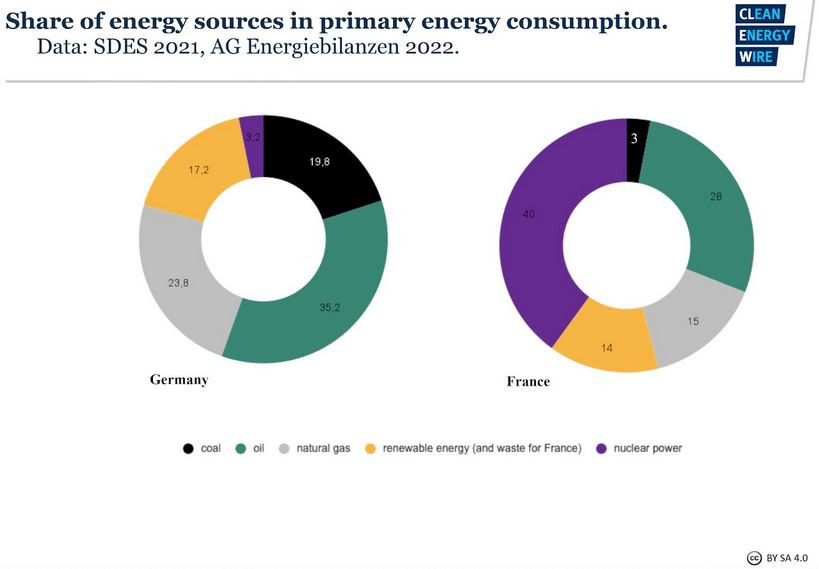

Primary Energy

In Germany, renewable energy accounted for some 17 percent of primary energy consumption in 2022. Total renewable energy use was 489 TWh, of which a little over half came in the form of electricity, some 40 percent in renewable heating and 7 percent in the transport sector, the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) said. The three last operating nuclear plants provided roughly 3 percent to the mix while the remaining 80 percent were mostly composed of fossil fuels, clearly led by oil (35%), followed by natural gas (24%), and coal (20%).

In France, the primary energy mix was composed mainly of nuclear power (40%) Primary production of renewable energies in 2022 in France amounted to 345 TWh, the ministry said, including biomass (38%), hydropower (17%), heat pumps (12%), wind power (11%) and biofuels (6%). Fossil fuels accounted for 46 percent of primary production, mainly with oil (28%) as well, followed by gas (15%) and a marginal share of coal (3%).

Electricity Production

Both countries covered roughly a quarter of their final 2021 energy consumption with electricity, which is supposed to replace the bulk of fossil fuel use: About 23 percent in Germany and 25 percent in France.

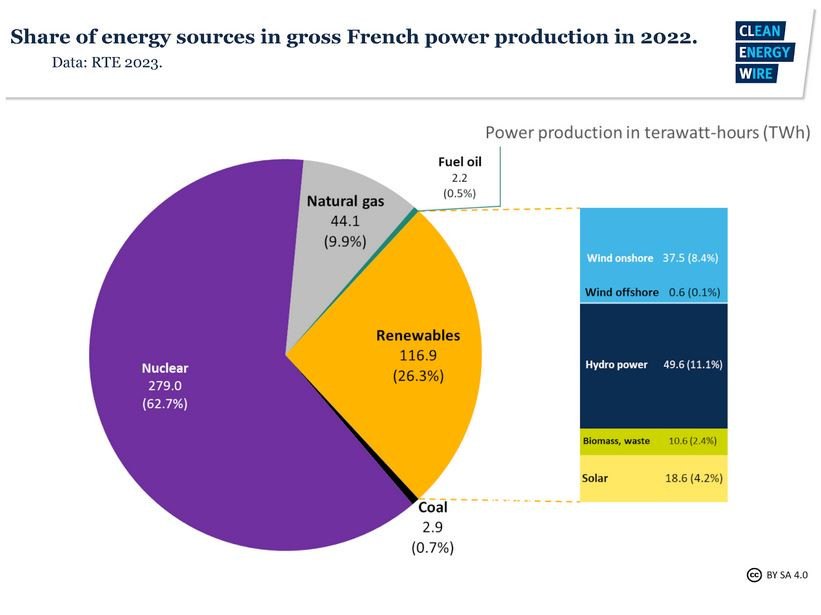

Regarding electricity generation, nuclear power dominated in France with a share of 63 percent, the highest share of any country in the world. Nuclear was followed by renewable power installations, with a combined share of about 26 percent. Hydro power accounted for the bulk of that share (11%) - followed by onshore wind power (8.5%), solar PV (4%), and biomass and waste (2.4%). Gas (10%) was far ahead of oil and coal (<1% each) in electricity production. Offshore wind still lurked at a share of 0.1 percent.

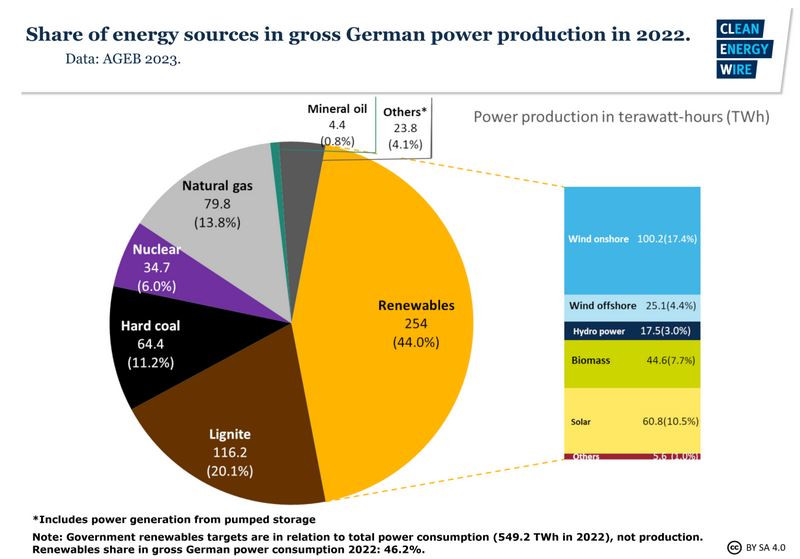

In Germany, renewables accounted for 44 percent of electricity production in 2022, dominated by onshore wind power (17.5%), followed by solar PV (10.5%), biomass (7.5%), offshore wind (4.5%) and hydro power (3%). The remainder was overwhelmingly composed of fossil fuels: Coal (hard coal & lignite) still accounted for over 31 percent and gas for nearly 14 percent, followed by nuclear (6%) and oil (<1%).

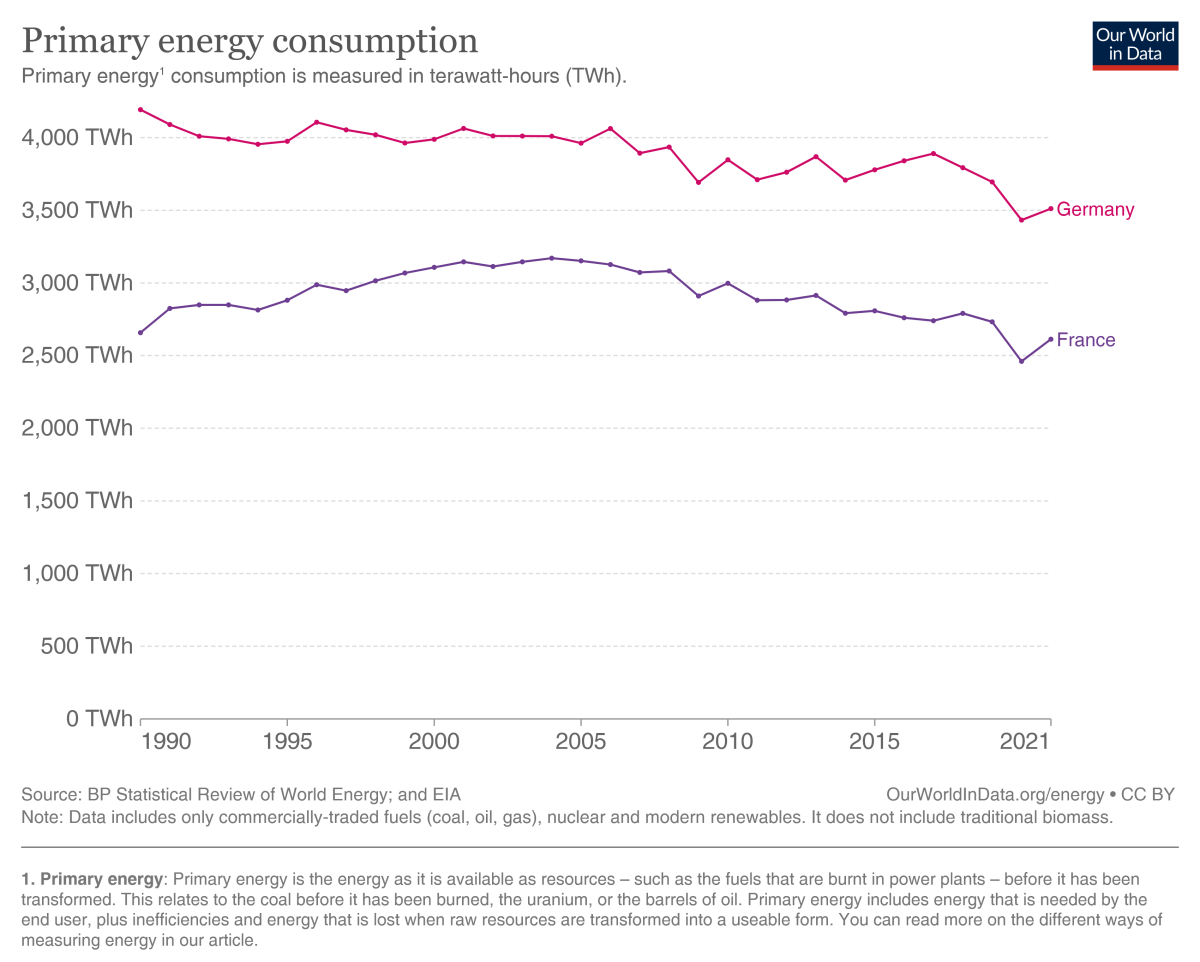

Energy Consumption Declines in Both Countries

Consumption has generally been declining in both France and Germany since 1990, at a somewhat faster pace than in the then re-unified Germany, where many industrial sites in the formerly communist eastern states were shuttered in the decade following reunification - while its strong recovery in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis delayed further cuts.

The German government has set itself the goal of reducing primary energy consumption by 30 percent by 2030 and by 50 percent by 2050 compared to 2008 levels. (Govt’ Energy Efficiency Strategy 2050). In 2022, it had achieved slightly over 18 percent reduction, less than the 20 percent-target envisaged already for 2020.

The latest addition to the French government’s sufficiency plan was announced in mid-2023, by the Ministry of Energy Transition. It called for a long-term sufficiency approach among the largest companies and across sectors. Alongside efficiency efforts, the current national low-carbon strategy calls for a 40 percent reduction in energy consumption by 2050.

While total energy demand is set to fall in each country, the demand for electricity will increase as industrial processes, heat generation and transport become more and more electrified. By 2030, Germany estimates a demand of 600 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity from renewable energies - based on higher gross electricity consumption of about 750 TWh.

French grid operator RTE estimates a demand of about 645 TWh of decarbonised electricity demand in 2050, pointing out it already stood at some 500 TWh in 2021.

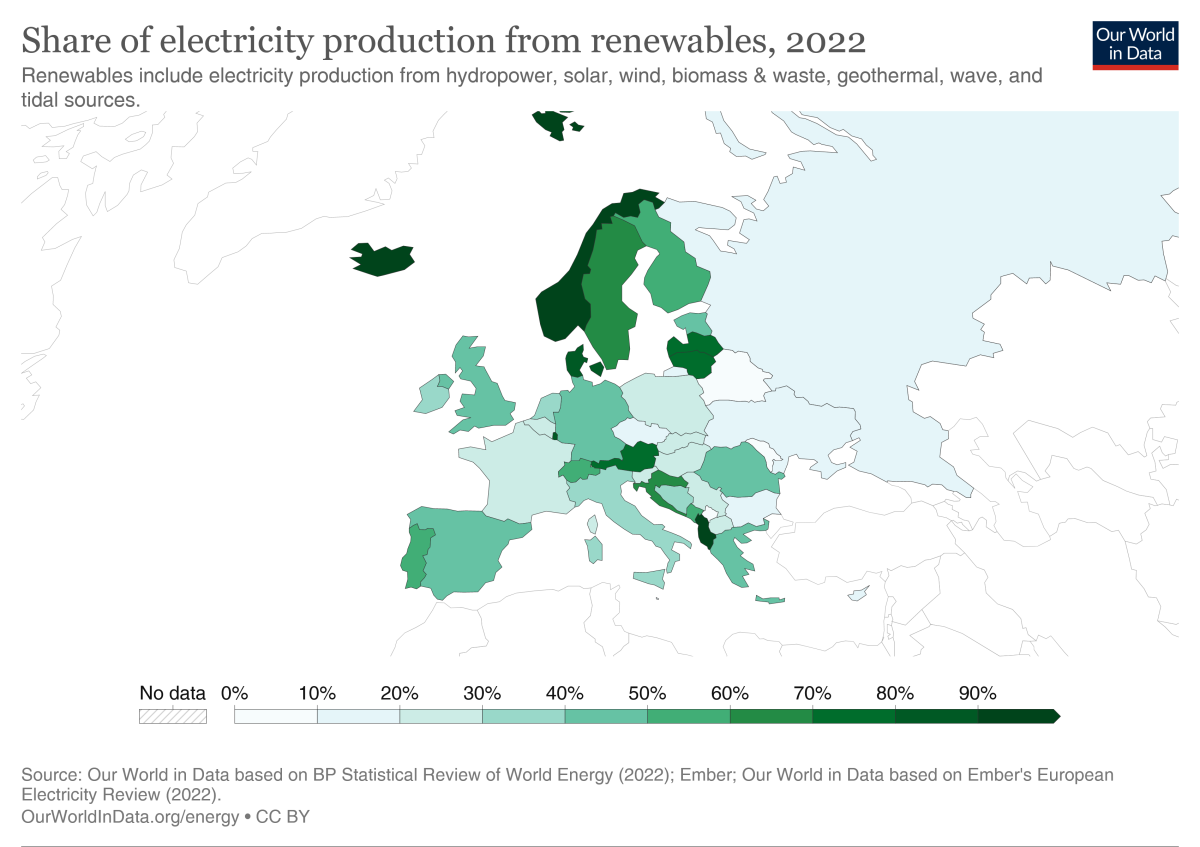

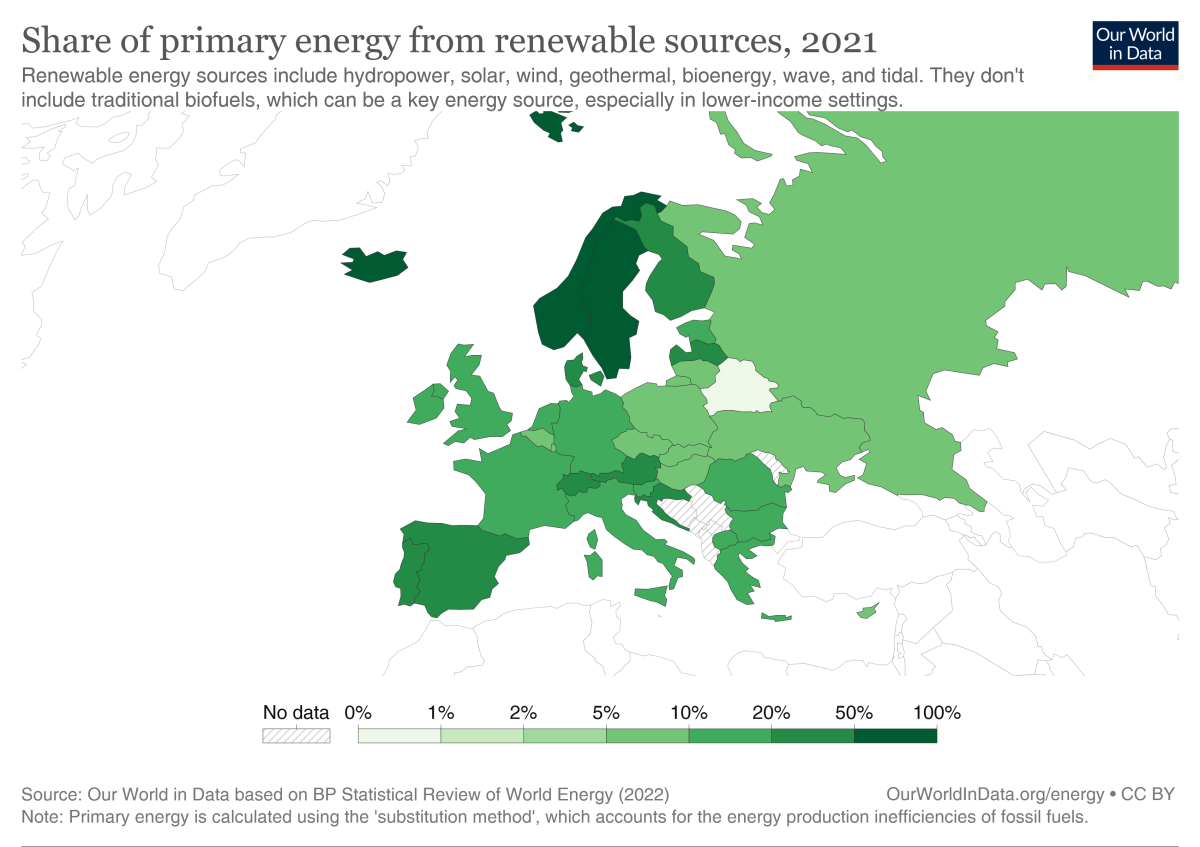

Renewables Set to Grow Fast Across Europe

On a European scale, EU states agreed to increase the share of renewables in the overall energy mix to 42.5 percent by 2030, leaving an option open to possibly reach 45 percent - which would almost double the 2023 share of renewable energy in the bloc.

In 2022, total renewable capacity in Germany stood at roughly 148 GW (139 GW in 2021). About 58 GW of onshore wind capacity was installed, roughly 8 GW of offshore turbines, about 67 GW of solar PV arrays, 5 GW renewable hydro power and nearly 10 GW bioenergy (IRENA 2023). Together they produced about 244 TWh of net electricity, some 7.4 percent more than in the previous year, according to research institute Fraunhofer ISE.

In order to achieve the national goal of 30 percent renewable energy in gross final energy consumption formulated in its energy concept (from 20.4% in 2022) - and of 80 percent in electricity production fixed in the latest reform of its Renewable Energy Act - the government in Berlin plans to implement an expansion of wind power to 115 GW by 2030. According to the government, this translates to a fast scale-up and ultimately the construction of four to five new onshore turbines per day. Offshore wind capacity is supposed to increase more than threefold to 30 GW by the end of the decade, while the projected 2030 capacity for solar PV is 215 GW.

Total installed renewable power capacity in France was 65 GW in 2022 (60 GW in 2021), composed of 25 GW hydro power, roughly 21 GW onshore wind, 17 GW solar PV, 0.5 GW offshore wind (with a further 8 GW already projected). In total, they contributed about 136 TWh to gross power consumption, also around 7 percent more than in the previous year, the French Energy Transition Ministry informed.

Paris wishes to develop its capacity gradually to reach a 33 percent share of renewable energy in gross final energy consumption until 2030 (it had reached 20.7% in gross final consumption in 2022), as fixed by the French Climate and Energy Law of November 2019. The long-term goal up to 2050 is to significantly increase installed renewable energy capacity, as set by French President Emmanuel Macron in his Belfort speech on energy policy in early 2022. He stated that solar PV production should be increased tenfold to over 100 gigawatts (GW), with 50 offshore wind farms to be deployed to reach a capacity of 40 GW, and that onshore wind power should be doubled to 40 GW.

While electricity generation with renewable power installations in France thus lagged behind that of its neighbours in 2021, the renewable energy share in energy consumption was closer to the European average.

Heating

In brokering a deal for its embattled building energy law, for its part Germany’s government has set a goal to ensure that all new heating systems installed in the country have a share of 65 percent renewable energy, with the legislation taking effect in some cases by 2024. In 2022, it also said that geothermal energy would be relaunched in the country. Researchers estimate that with an annual output of more than 300 TWh, the technology could cover more than a quarter of Germany's annual heat demand. The government is currently in the process of assessing the potential for district heating in the country, which according to industry groups could be used to decarbonise heating in about half of all households. Up to 100,000 households could be connected to district heating annually, according to the involved ministries.

In France, the aim by 2030 is to develop renewable heating (with a target of 38%) as set by the Pluriannual Energy Program (PPE), adding more than 100 TWh thanks to the ramp-up of heat pumps, geothermal energy, biomass and biogas. So far, heat production still relies mainly on fossil fuels while it accounts for half of all energy consumption. Moreover, a “unique” project regarding district heating exists at the French-German border, where the first cross-border district heating system is scheduled to start supplying French households with German waste heat by 2027.

Electric Mobility

The sale of combustion-powered vehicles has already been planned to end in France in 2040 and through common European goals, this date might be advanced to 2035. As of April 1 2020, there were more than 312,000 electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles on the road in France (including 246,000 electric vehicles). In May 2023, France reached 100,000 charging points open to the public. This represented a 270% increase in one year. France is now the second-most equipped country in the European Union behind the Netherlands. Its national action framework defines objectives for the deployment of electric recharging points (7 million public and private recharging points by 2030); gas refueling (CNG, bioGNV and marine LNG); hydrogen refueling.

In Germany, the government currently aims to have 15 million e-cars on the road by 2030 and one million public charging points to enable the shift to electric mobility. Industry groups have challenged the targets and Germany has sought to keep combustion engines an option in Europe if they are powered with synthetic e-fuels. As of 2022, there were roughly around one million purely electric cars on the road, and around 66,0000 publicly accessible charging points. The bi-directional charging of e-cars has so far not been integrated into the government’s official flexibility and storage projections. According to the transport ministry’s “Master Plan for Charging Infrastructure,” bi-directional charging concepts will be integrated in future infrastructure expansion. It argues that the legal and technical implications of the technology so far lack a solid footing, promising to work on a proposal for mid-2023.

An agreement at the EU level for the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR) aimed at laying the groundwork for Europe-wide charging infrastructure has been hailed as an important step by Germany’s automotive industry association (VDA). However, it warned that the planned maximum distance of 60 kilometres between charging stations is too long to make motorists confident about having constant access to chargers on transnational trips.

A 2023 comparison of support for the roll-out electric mobility in France and Germany by the NGO International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) found that the former currently looks better equipped to enable a comprehensive adoption of e-cars by making them easier affordable to people with low incomes. “Germany might run the risk of a fragmented transition,” the ICCT said.

Energy Storage

In the power plant list of the Federal Network Agency (as of November 2022), there are currently 142 pumped storage and battery storage plants with a net nominal capacity of approximately 10.2 GW listed in Germany. Research institute Fraunhofer ISE sees a total demand of about 105 GW in 2030 and 180 GW in 2045. Researchers have stressed that the need for storage capacity can be reduced by improving interconnections with neighbouring countries.

Regarding hydrogen as a storage, Germany will need between 95 and 130 terawatt hours (TWh) of the synthetic gas by 2030, including derivatives such as ammonia, methanol or synthetic fuels, partly made with fossil fuels and partly with renewables. Fifty to seventy percent would be covered through imports, and the government plans to develop an import strategy.

In France, a 2022 information report by Senate underlined a strategic in developing energy storage, noting that only hydropower provides relevant capacities. Installed hydropower capactiy stood at some 25 GW, with 5 GW of pumped storage. However according to RTE, hydraulic stocks in 2021 were 24 percent lower than in 2020. Moreover, 2022 was marked by an exceptional drought and hydraulic storage levels were significantly below historical values until early autumn, although storage levels increased again by early 2023.

According to RTE, non-hydro storage has an installed capacity of 292 MW. As of July 2022, France had 123 battery storage facilities with a capacity of 236 MW, of which 4 were connected to the transmission grid and the rest to the distribution grid, highlights the French energy regulatory commission (CRE). Moreover, at least 160 MW of additional storage will be deployed up until 2028.

The country also has a Hydrogen Development Strategy for decarbonised hydrogen, with massive investments. The France Hydrogen Association wants to reduce the currently dominant production of gray hydrogen to 1.07 million tons per year by 2030, while EU plans foresee a production of 10 million tons of green hydrogen in France and imports of 10 million tons in that year.

Power Grid

The need for grid expansion in both countries is underpinned by the EU’s 2030 interconnection target, which stipulates that member countries are able to export at least 15 percent of the power produced on their territory. As of 2022, Germany and France had five electricity interconnectors in operation and was planning the construction of two additional ones, newspaper Handelsblatt reported. The countries are also connected for natural gas transports and strive to intensify their capacity for molecule-based energy trade for future hydrogen transports.

Expanding the power transmission grid to enable a smooth distribution of electricity generated with decentralised renewable power installations remains a key challenge for Germany to implement its national energy transition targets and to act as a European hub due to its central location. The country’s transmission grid operators expect electricity consumption to double to 1,000 terawatt hours (TWh) by 2045. The identified projects for new lines that year comprise a total route length of 14,197 km and are estimated to cost of around 128 billion euros.

France connects the Iberian peninsula to the rest of the EU and also maintains connections to the UK. By 2035, grid operator RTE plans to double the interconnector capacity in the framework of the Ten-Year System Development Plan (SDDR). Transmission capacity is expected to increase from about 15 gigawatts today to about 30 gigawatts by 2035. For French national transmission networks, RTE plans to invest 33 billion euros over the next fifteen years to modernise equipment whose average age now exceeds 50 years.

Nuclear Power: Phase-Out for Germany, Renaissance for France

As far as nuclear power is concerned, Germany closed its last plant in April 2023, following a short delay caused by the energy crisis, while France plans to invest significantly in the sector. France and other European neighbours had appealed to Germany to further postpone the shutdown of its remaining three reactors to serve as a backup-capacity in the energy crisis. However, the German government ultimately completed the phase-out that had been prepared for more than 20 years, arguing the additional capacity provided by the reactors is of little use in stabilising the system. The shutdown did not impact power prices negatively in the immediate aftermath, as critics had warned. There is no agreement on building a nuclear waste repository for the radioactive legacy of Germany’s nuclear power era and the deadline for an ongoing search that was planned for 2031 was has been postponed in 2022.

In France, by contrast, 61 GW of nuclear capacity was installed in the same year (SGPL) in 56 reactors, and one novel EPR (European Pressurised Reactor) was under construction (Flamanville). However, twenty-six of the 56 French nuclear reactors will reach the end of their fifty-year operating life in 2035. They then will have to pass an in-depth safety inspection in order to receive a runtime extension for another ten years. President Macron also announced his plan to not only extend the operation of existing plants but launch a “nucelar renaissance” with the construction of a series (at list six and possibly eight more by 2050) of new second-generation EPR.

Even without a renaissance, France dominates the EU’s nuclear power industry, boasting 52 percent of the bloc’s total capacity in 2021, when Germany still had several reactors operating. France also boasts the second largest nuclear power capacity in the world, ranking behind the U.S. and slightly ahead of China af of 2023.

Different nuclear scenarios exist for France, with more or less renewable energy, considering that at least 20 to 60 percent more electricity (compared with 2020) shall have to be generated by 2050 to meet growing electrification needs, according to France's Transmission System Operator (RTE) 2021 report.

Difficulties in the French reactor fleet led to a sharp reversal in Franco-German electricity trading. While France had been Germany’s most important foreign supplier in 2021, exports decreased 62 percent in the following year - marking the first year since 1990 when France had a negative export balance with its neighbour, according to Germany’s statistical office Destatis.

Fossil Fuels: Germany Leads Consumption with Gas as Key Driver

As of 2022, fossil fuels still cover over three quarters of Germany’s gross energy consumption - with oil providing about 35 percent, coal 20 percent and gas nearly 24 percent. However despite redeploying some of its already retired coal plants during the energy crisis, so far the country seems prepared to achieve its 2038 deadline to complete the phase-out of coal - or perhaps even faster, if eastern coal regions can be made to follow their western counterpart’s example and attempt an exit as early as 2030. However, to replace gas, coal in 2022 fed almost 8.5 percent more electricity into the grid than in the previous year.

While the use of oil (-24%) and coal (lignite -63%, hard coal -50%) has shrunk between 1990 and 2022, that of natural gas has increased markedly. In 2022, due to the supply cut from Russia, consumption was only 21 percent higher than 1990 - while in 2021 it was 41 percent higher. There currently is no exit date in Germany, although the 2045 climate neutrality target greatly limits the extent to which it can be used until then. The government currently plans to even expand gas-fired power production but aims to make new facilities ready to work on hydrogen as well, to supply industry processes and other sectors that are difficult to decarbonise otherwise.

Regarding oil consumption, mainly for transport and heating, there are no phase-out plans and neither any concrete proposals to exit combustion engines. However, a mix of carbon pricing in transport and heating and subsidies for electric cars and renewable heating are supposed to deliver a gradual transition away from oil.

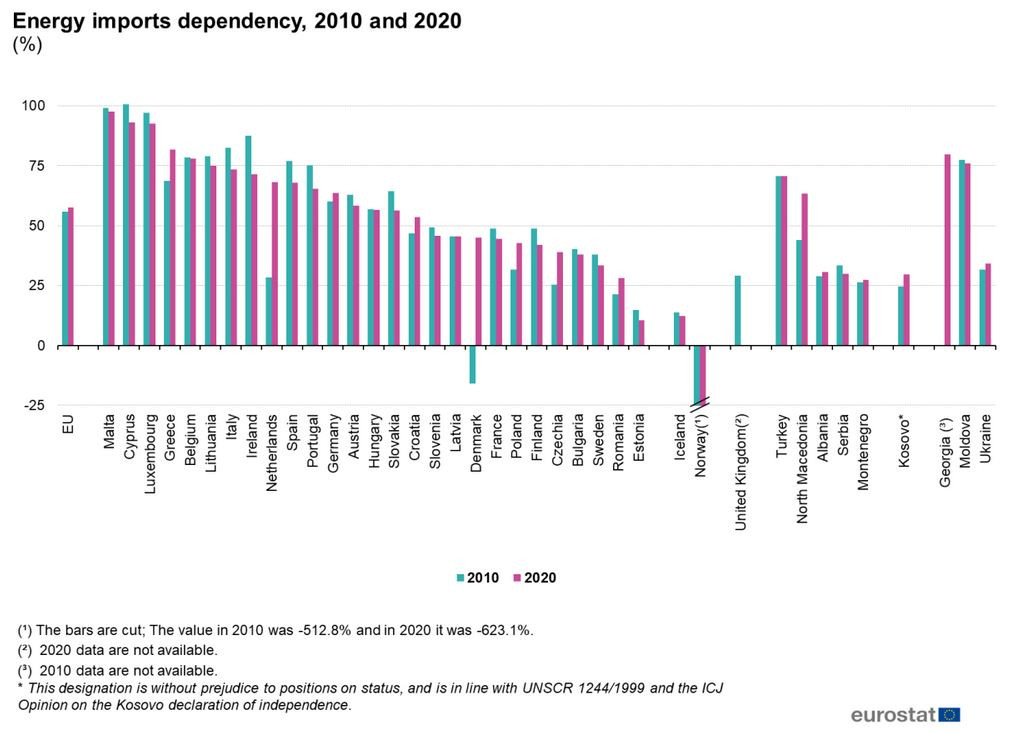

Germany’s energy import dependency, mainly consisting of fossil fuels, was higher than the EU average in 2020, with 63.7 percent of all energy consumed, compared to 57.5 percent on average for member states. The figure for France was 44.5 percent.

Since 1990 France's consumption of coal and oil has decreased by 72 percent and 27 percent, respectively. Conversely, natural gas use increased by 44 percent. With nuclear and hydroelectric production declining in 2022, gas-fired power plants were also called upon at an unprecedented level (+34% in metropolitan France).

France in 2021 affirmed that it would end all funding for oil projects by 2025 and gas projects by 2035. According to all the transition scenarios studied, fossil fuel investments will have to be halved before 2030, and disappear almost entirely by 2040, the I4CE think tank underlines.